Gulf states seek to diversify economy by promoting historical sites

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As Gulf states look to diversify their oil-dependent economies, they are pinning hopes on untapped heritage tourism to foster growth.

In Saudi Arabia, magnificent antiquities, long impregnable to global tourism, are being promoted as must-do itineraries for travellers seeking undiscovered locations. Other regional states, already on the tourism map, are honing their offering away from sun and sea getaways towards visitors seeking to delve into the histories of Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s north-western oasis of AlUla, the largest site of the ancient Arab Nabataean civilisation to be found south of Jordan’s Petra, opened to tourists in October after two years’ refurbishment.

The country’s first Unesco site, Hegra, showcases 100 tombs and facades cut from sandstone outcrops surrounding the Nabataean city of Madain Saleh on the incense trading route that reached its peak in the two centuries before and after the common era.

Nearby Dadan, a city dating back to the 1st millennium BCE, is another destination being readied for tourists alongside the rock inscriptions of Jabal Ikmah.

“Saudi Arabia wants to leave behind conservative Islamic insularity for a more globalised outlook,” says Tim Power, a consultant archaeologist based in the United Arab Emirates. “When people think of Egypt, they think of the Pyramids – now the kingdom’s leadership wants them to think of AlUla, a positive image of rich cultural heritage,” he says.

The emergence of this multi-billion-dollar sector has prompted Abu Dhabi’s Zayed University to develop a masters’ degree in heritage, development and entrepreneurship. Mr Power, who is advising on the course, says this “MBA for the heritage industry” reflects growing market demand.

Much of this demand has been fostered by the socio-economic opening up under the crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who has identified the heritage industry and cultural sector as opportunities to diversify the economy in preparation for 'the end of oil', as well as a way to forge a common national identity for the kingdom’s growing youth population.

On the outskirts of Riyadh, the birthplace of the House of Saud, Al-Diriyah, is being transformed into a cultural destination as part of a $17bn project called Diriyah Gate. Within the historic capital, the district of Al-Turaif will open to the public in January, unveiling several kilometres of walkways dotted with hundreds of restored buildings, alongside museum galleries and exhibitions tracing the capital’s history.

“The Saudis want Diriyah, the kingdom’s spiritual birthplace, to take its place among the great heritage sites of the world,” says Mr Power. “They are saying our culture is relevant to the world.”

As the crown prince invites tourists in, however, the kingdom’s image as a brutal dictatorship has been reinforced by crackdowns on political dissent, including the horrific murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the detention of women’s rights activists.

This vacillation between liberalisation and authoritarianism has plagued Saudi Arabia’s image, threatening to put off would-be visitors to a still conservative society where alcohol remains banned.

Advocacy group Human Rights Watch last month launched a campaign against what it describes as the government’s efforts to whitewash a “dismal rights record” by hosting major cultural and sporting events.

The rush towards cultural tourism is visible elsewhere around the Gulf.

Ras Al Khaimah, the northernmost member of the United Arab Emirates, has long pitched itself as a sun and sea destination with the added benefit of a diverse topography including the UAE’s most impressive mountain ranges.

With global tourism struck down by coronavirus, Ras Al Khaimah has turned to local demand through the pandemic. Tourist numbers suffered a decline of only 35 per cent from January to August as overseas visitors were replaced by UAE residents vacationing in the emirate.

“What made us attractive was the nature, the sprawling spaces that make social distancing comfortable,” said Raki Phillips, chief executive of the Ras Al Khaimah Tourism Development Authority. “And we believe the cultural side is a pivotal part of the allure.”

Mr Phillips says the emirate is now moving beyond nature-driven adventure tourism, including the world’s longest zip line in the world, to highlight the emirate’s history.

The government has for years been gathering information and restoring sites and creating experiences to tap a history extending back to its first settlers 7,000 years ago.

More stories from Art and Culture in the Gulf

World unites to help save Iraq’s archaeological treasures

Iranians escape harsh Covid realities by streaming real-life dramas about power

Arab authors call for boycott of UAE book awards after Israel deal

Boosting Gulf’s economy leads to building more art districts, not museums

UAE becomes an incubator to develop careers of local emerging artists

Al Jazirah Al Hamra, abandoned in the 1960s, is the UAE’s last standing traditional village. Restored to showcase the coral-stone architecture of the Gulf coastal regions, it offers visitors an undisturbed glimpse of life before the discovery of oil, with a fort and ornate houses owned by pearl merchants.

A pearl farm in a lagoon nestled below the Hajar mountains has proved to be one of the emirate’s fastest-growing attractions, where visitors learn about the history of pearling, which died out in the 1930s with the invention of the cultured pearl.

Mr Philips believes that, over time, more than 20 per cent of the emirate’s tourism offering will be cultural.

“Ras Al Khaimah was positioned for adventure,” he says. “Now we have diversified and culture is a big part of the proposition.”

Other Gulf sites to visit

Bahrain Fort: Under this singular example of a Portuguese fort, visitors can see unearthed archaeological findings that trace the entire history of the Gulf states, spanning back to the Greco-Roman period into the Bronze Age.

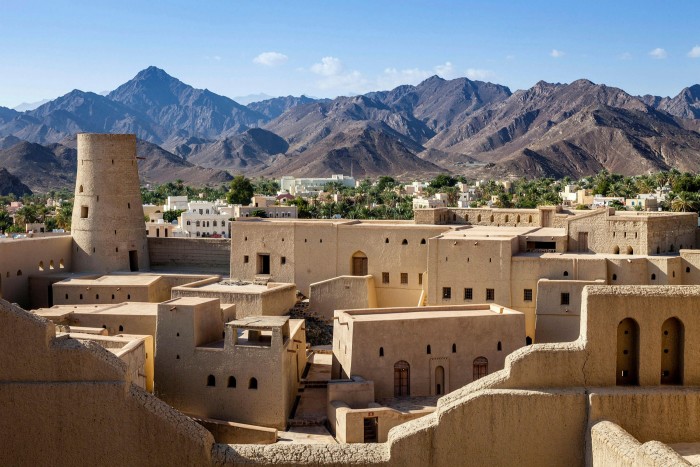

Oman’s Bahla Oasis: Dominated by its impressive 13th century fort, the walled town of Bahla, dotted with mud brick houses, was once the sultanate’s capital and is an outstanding example of medieval Islamic architecture and historic water engineering practises.

UAE’s Al Ain Oasis: Within Abu Dhabi’s garden city, the oasis of Al Ain harks back 4,500 years, when its earliest residents tamed the desert with traditional falaj agriculture. Visitors can meander through shaded pathways beneath a canopy of 147,000 date palms.

Comments