Will this truly, finally be ‘the year of the stockpicker’?

Simply sign up to the Equities myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

As surely as new year resolutions fall by the wayside, January brings declarations that the coming era will be a good one for stockpickers. Will they prove true in 2022?

Morgan Stanley beat the rush to declare in November that 2022 would be “the year of the stockpicker”. The ferocious economic and financial cross-currents would make it an unusually fertile environment for active equity fund managers, the bank’s strategist Michael Wilson argued.

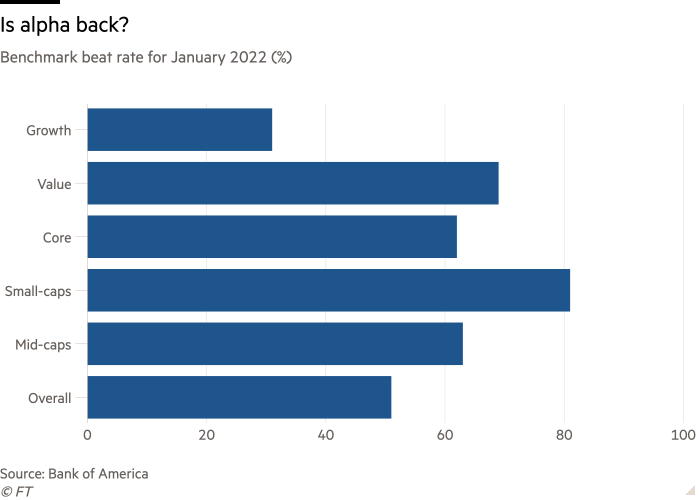

For some prominent investors, this seems to have been a jinx. Several star mutual fund managers, such as Fidelity’s William Danoff, have already taken a beating this year. But more broadly, the early signs are actually good. Despite the recent choppiness of financial markets, 51 per cent of US equity fund managers outperformed the stock market in January, according to Bank of America.

This might seem underwhelming, yet the average was dragged down by a miserable month for growth-focused funds, which were clobbered by a slump in technology stocks. More value-oriented investors enjoyed a 69 per cent beat rate, and 81 per cent of those that focus on smaller stocks surpassed their benchmarks. “Alpha is back,” argues Bank of America’s Savita Subramanian, referring to the investment term for delivering above-market returns.

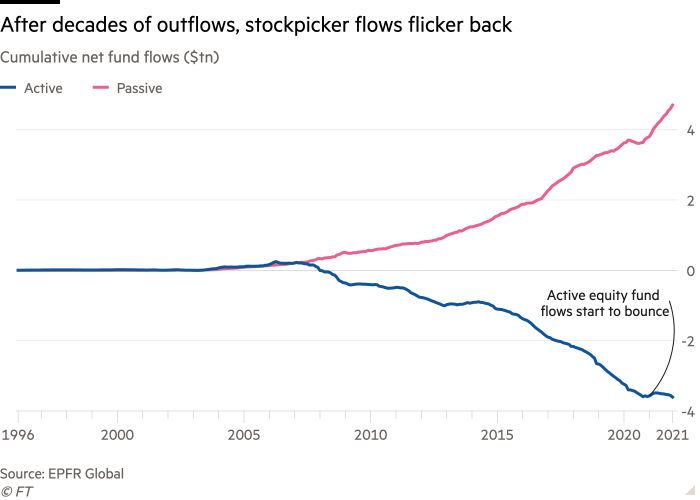

Some investors agree. After almost unceasing outflows for two decades, active equity funds globally took in $111bn last year, their best year since at least 2000 according to research group EPFR. The optimism is understandable. It is true that the market environment affects the performance of active management, and current conditions look supportive.

These days, the investment industry often categorises stocks by financial characteristics rather than by industry or country. These theoretically more fine-tuned classifications — often called factors — can be used to better understand a stock’s movements, an investment fund’s style and the risks a trader might be taking, and to identify different market regimes.

Some traditionalist fund managers detest such categorisation, seeing it as a silly attempt to shoehorn what is still often an art into a mathematical construct. Like any methodology it has weaknesses. But it is a useful framework, nonetheless. Think of factors as flavours, stockpickers as chefs, and the market as a fickle diner whose preferences can abruptly change.

Broadly speaking, active managers as a group tend to tilt towards factors known as “size” and “value”. They often eschew bigger companies in favour of smaller ones, and are always on the lookout for bargains. The problem has been that the last decade — and especially the pandemic era — has been unusually great for big companies, and often pricey ones. That tends to favour passive funds.

“Active/passive cycles are not dominated by manager skill,” Scott Opsal, director of research at The Leuthold Group, argued in a recent report examining the phenomenon. “Instead, they are driven by overall market conditions that tend to reward either active or passive at any given time.”

At the same time, skilled stockpickers should do better when correlations are low and dispersion is high. In other words, they want shares to march to their own drumbeat, and the difference between good and bad ones to be as wide as possible. Low correlations lead to more opportunities, while high dispersion increases the potential profits from those opportunities. Unfortunately, the last decade has generally given us a high-correlation, low-dispersion world.

Change is now afoot. Measures of correlations and dispersion are decent and improving, according to Bank of America, and value stocks are enjoying a renaissance. Many analysts expect a tumultuous year that will present even more openings for expert money managers.

So will the market favour the varied dishes of active management more than the basic cooking of passive funds in 2022? Perhaps. There have been a few odd years where a majority of active managers have outperformed, and this could be another one. But it would still take a brave — or desperate — investor to bet on it.

There have been many market epochs where value stocks have done well, or correlations and dispersion have led to abundant opportunities, without altering the fundamental data. In any given year the average active manager underperforms, and in the long run the vast majority do.

Despite the undoubtedly decent set-up, the final-year tally is likely to prove as grim for stockpickers as it has since performance numbers started being collated in the 1960s. But as one unusually honest portfolio manager told the Wall Street Journal in 1973 when quizzed about this: “You know how it is. Hope springs eternal.”

Twitter: @robinwigg

Comments