Give blood. Go on

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I wish I could say it was a noble impulse that drove me to become a blood donor – but if I’m honest, it was guilt. I had hurried past the NHS blood van parked outside my kids’ school, muttering my excuses, so many times, and then one day in the autumn of 2019 I finally caved.

I regret I didn’t do it sooner. Because it’s been profound in its own quiet way. You can give money or time to good causes – but there’s something incontrovertible about opening up a vein.

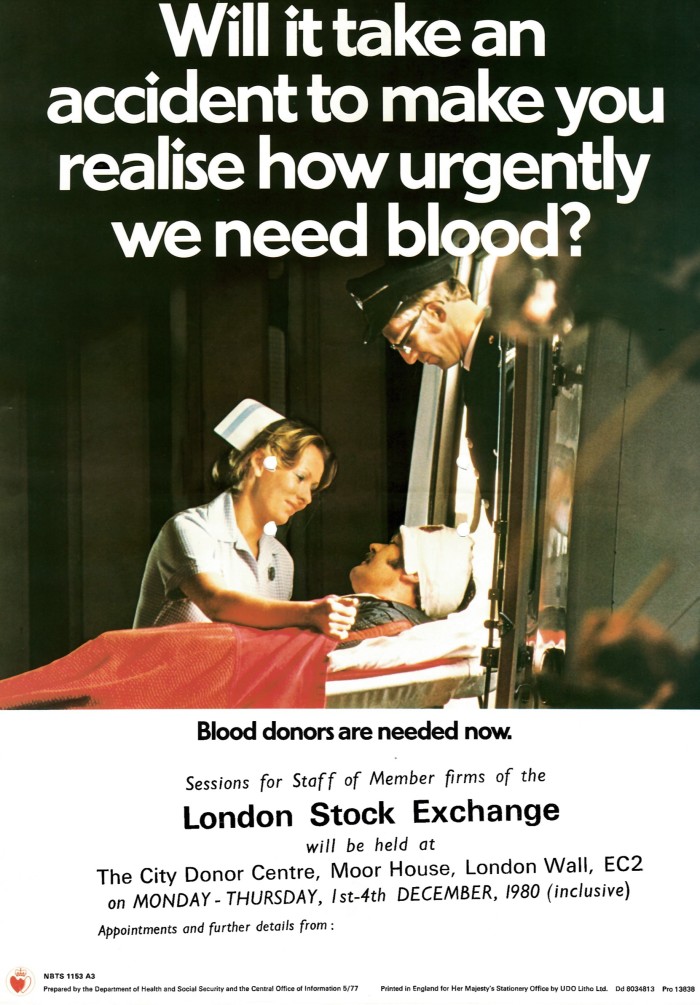

Does it hurt? Yes, a little bit. But the overriding sensation is more strange. During those five to 10 minutes you’re hooked up to the pinging machine, you’re in a state of abject vulnerability. There’s usually a radio burbling in the background. Cheery nurses go round swabbing arms and dispensing restorative biscuits and squash. It’s almost prosaic – but then you look around at all those prone figures, lost in thought, and feel the weight of untold stories.

You have no idea who gets your blood – but they send you a text that tells you where it’s gone. “Your donation has now been issued to the Homerton University Hospital.” The idea of part of me whizzing across town is always something of a thrill. Once, after I had donated, a nurse told me my blood had been earmarked for newborn babies in ICU. I thought of my own son’s first week in intensive care and blinked back tears.

Being a drinks writer and a blood donor might sound like incompatible life choices. I’ve heard every joke going about my blood being overproof or pure grand cru. But that’s the thing: almost anyone can do it. And however wealthy or powerful or famous you are, you can only give 470ml, or what they call one “unit”.

Around two-thirds of the blood donated to the NHS is used to treat medical conditions including anaemia, cancer and blood disorders. Nearly one third is used in surgery and emergencies including childbirth. A small proportion is also used for training and research. The NHS aims to have enough reserves to last six days – but in October blood stocks fell to below two days’ worth, triggering an amber alert. The Christmas period, when donors get ill or go away, or the times where there’s a public holiday when people can’t donate, can be especially fraught – a pattern which is also found across other European countries, America and Australia; it’s also seen during Ramadan.

How to donate

England blood.co.uk

Eire giveblood.ie

Northern Ireland nibts.hscni.net

Scotland scotblood.co.uk

Wales welsh-blood.org.uk

Of the four main blood groups – A, B, AB and O – O negative (the universal blood group) and B negative are the most vulnerable to shortfalls. But there are other types of blood that are often in critically short supply – at the time I’m writing this, for example, there are only three units of the “Bombay” blood group (first identified in India) in stock across the whole of the UK. Blood banks on both sides of the Atlantic are also urgently in need of black heritage donors, as they are more likely to have the blood types Ro and B positive, which are needed to treat the growing number of patients suffering from sickle cell disease.

Blood donations are strongly skewed to wealthy countries. The World Health Organisation reports that 40 per cent of the 118.5mn blood donations collected globally come from high-income countries, home to 16 per cent of the world’s population. And there are also big disparities in the way that blood is used. In low-income countries, around half of blood transfusions are given to children under five years old; in high-income countries, the most frequently transfused patient group is over 60 years of age.

Men can give blood every three months. Women every four. The real hardcore are platelet donors who commit to a more intensive regime and can give every two weeks if they want.

In her 23 years as a nurse in NHS blood and organ donation, Ella Poppitt has seen it all. “Some people do it because a relative or a child was really ill and needed blood and they want to give something back. Others might be honouring a parent who used to donate and there’s a legacy aspect to it. You get a real cross-section of the community, and there’s a real sense of belonging in that moment – everyone’s really pleased to see you and grateful for what you’ve done.

Lab-grown blood may be an option in the future, particularly for those with very rare blood types. The world’s first clinical trial of lab-grown blood in humans is now under way at hospitals in Bristol, Cambridge and London. But artificial blood is vastly more expensive than real blood. And at this stage scientists are still trialling tiny amounts – equivalent to just a couple of spoonfuls – until they have a better idea of how it, and the body, responds.

For the time being, at least, the health system, and the lives within it, will continue to depend on people rolling up their sleeve.

Comments