The ultimate heirloom

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The business of jewellery has always been a family affair: the craft and savoir faire passed down from one generation to the next; or the sparkling gems made to mark occasions such as engagements, weddings, births and anniversaries. “Anyone in our industry who gets to do what we do feels hugely privileged,” says Sophia Hirsh, the second-generation jeweller who, when it comes to creating heirlooms for clients, has had a private, front-row seat to some precious moments.

So what about a jeweller’s own family pieces? Do they carry the same meaning, the memories and sentimentality?

For the second-generation Jeremy Morris, his family heirloom is a 7.95ct sapphire with a rare, unusual colour that he describes as “very dark purplish-pink – it’s a specimen”. His father purchased it in the late 1970s from the Malaysian royal family. “It’s an old mine material-type stone – they are always a bit more charming, the colours a bit more special.” With no inclusions, the sapphire has the flavour of early Burmese rubies, and indeed, ever since arriving in the family, has sparked much bickering about whether it is in fact a ruby (it’s been confirmed multiple times not to be).

In the past 40 years, Jeremy’s mother has been the main custodian of the sapphire, which has been repolished and remounted into three different jewels so far. “My mum wears it all the time and didn’t want to scratch it any more, so we’re currently setting it into a necklace [from a ring].” Jeremy has five children – three daughters and two sons – but none has been earmarked for the family gemstone yet. “They can all fight over it later,” he laughs.

Yasmin Hemmerle may be known as the other half of Christian – the fourth generation Hemmerle whose late-19th-century ancestors supplied metals and orders to the Bavarian royal family – but jewellery has coursed through Yasmin’s own veins since she was a child. Much of that passion was instilled by her paternal grandmother, who lived two floors below in the same building. “I used to love going downstairs and watching my grandmother getting dressed. Jewellery was a huge thing for her, it was a ceremony to watch: she’d put on her necklace, her bracelet, her earrings and watch… Everything kind of matched,” recalls Yasmin. It was also a chance to try on some jewels herself, especially a long beaded necklace, that “at my age, would practically go down to my knees”, says Yasmin. “I loved it – and I loved watching her. It just fascinated me.”

For Yasmin’s wedding to Christian, her grandmother gifted her an old Victorian-style cross pendant set with diamonds, which had been given to her by Yasmin’s grandfather early in their marriage. It was the only jewellery she wore that day, alongside a pair of diamond drop earrings set in blackened silver, an engagement gift from Christian. The necklace is quite a large jewel, says Yasmin, which today she wears as a statement piece if she’s going out. “It reminds me of my wedding day,” she says.

More often, she wears a lapis lazuli, diamond and turquoise brooch that was passed down by her maternal grandmother. The piece was originally designed by Yasmin’s grandfather, an art collector and artist. (“He was one of the most creative men I have ever met, something I appreciate even more now that I’m older,” says Yasmin.) Inherited by Yasmin via her mother, the brooch has a kind of protective quality with its evil eye-like look and link to the past. “It reminds me a lot of my granny – how she used to laugh, her salt-and-pepper hair… It’s like a vessel with all the memories inside. When you have a jewel close to you, obviously those who wore it before are more present.”

Becoming a Hemmerle has only enriched the stories around her jewellery box. Cue a signature wooden Harmony bracelet, a piece that Christian had bespoke-made for their second wedding anniversary. Yasmin wears it every day. “It’s my Wonder Woman bangle, my safety blanket – it’s everything all in one,” she says, adding that she hopes to pass it down to her son and someone that he loves.

Jewellers love telling clients not to hide their jewels away in a safe but to wear them often – something that Boodles both preaches and practices. Take the aquamarine suite that is today in the custody of Annie Wainwright, wife of the current managing director, Michael Wainwright. The stones date back to 1982, when Michael’s parents – his father was Boodles’s chairman – acquired the aquamarines on holiday in Madagascar, subsequently setting them into a brooch. Annie inherited the jewel around 10 years ago, notably while her mother-in-law was still alive. “She was going to leave them to me very sweetly in her will, but then said, ‘What’s the point of giving them to you when I’m dead? I can’t see the enjoyment of you wearing them,’” recalls Annie. “She wanted to see my reaction and everything else.”

The stones were reset into the current design – a stunning 24ct drop pendant and matching earrings featuring a dragonfly motif. “It was made into something more modern and more appropriate for me, which [my mother-in-law] was very much in favour of,” says Annie (her mother-in-law passed away two years ago). Today, Annie wears the earrings more casually with jeans, but the full suite is reserved for formal occasions – such as a family wedding last summer. It was here that Annie and her 27-year-old daughter, Honour – a sixth generation of the family now working in Boodles – hashed it out to wear the jewels (the younger generation won). “Honour was very keen. It was a way to bring Granny to the wedding, if you like,” says Annie.

Mario Buccellati

Buccellati’s 1929 bracelet that Maria Cristina Buccellati’s father discovered in the ’80s

Maria Cristina Buccellati’s treasured heirloom is a 1929 silver and gold bracelet set with rose- and brilliant-cut diamonds. “It’s not a sparking, bling bling bracelet,” says the third-generation jeweller. “It’s something extremely discreet.” Made by her grandfather Mario, Buccellati’s founder, the piece was acquired in the 1980s by her father and later gifted to Maria Cristina on her 18th birthday. “My father wanted me to have something that I could remember him and my grandfather by at the same time,” she says.

When her father first saw the jewel some 40 years ago, he “went crazy”, recalls Maria Cristina. “It was love at first sight. My father was born in 1929, so he had no idea that this bracelet existed. But he could recognise the workmanship and detail. It’s all pierced, like lace. Every single hole you see is made by hand – with a little soul.”

As such an historic piece, it’s no surprise she has worn it only twice – for her own wedding and for her niece’s. The jewel is really more a showcase of Buccellati’s savoir faire, and has been exhibited in The Kremlin and Smithsonian Institution. “People can see the refinement of my grandfather’s work – and I can assure you, we have no more artists who can do that kind of work,” she says.

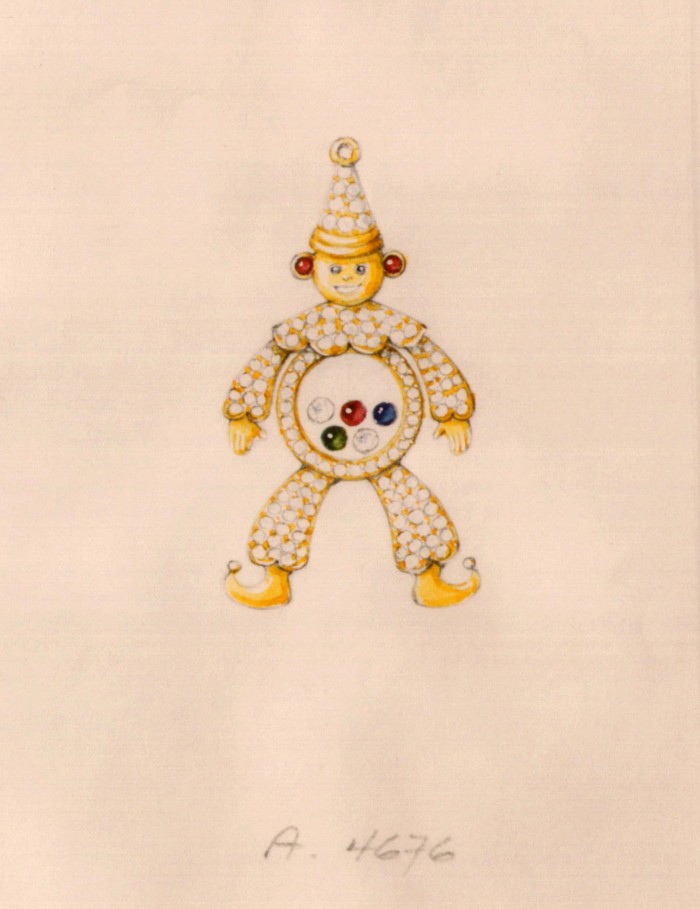

Family jewellers truly live and breathe the business. Caroline Scheufele is the second generation to run Chopard; she was only 16 years old when she inadvertently introduced jewellery into what was then only a watch company. A huge fan of the circus, Caroline created a clown jewel as one of her very first sketches, embellishing it with the spirit of Chopard’s Happy Diamonds watch, where diamonds appear to float around a watch movement. That Christmas, her father presented her with the jewel incarnate, as a clown pendant with a fully articulated head and arms. “It was a complete surprise. He took the drawing, it disappeared and then showed up at Christmas,” recalls Caroline. “It was one of my very first pieces of jewellery.”

The Chopard clown diamond pendant that Caroline Scheufele’s father had made for her

Caroline Scheufele’s sketch of the clown diamond pendant, which che drew at the age of 16

Caroline often wore the necklace to dinner with her parents and clients, and one day, while visiting Chopard’s workshop, she saw similar clown jewellery being produced. “I said, ‘Daddy, I thought this was my unique piece?’ And he replied, ‘We made a small, limited series because everyone loved it. This is commercial. You will understand later.’”

And how she did. The design kick-started Chopard’s foray into jewellery, particularly its Happy Diamonds line. Today, Caroline still wears her father’s Christmas present, and clients still comment on it. “It has a lot of value and meaning to me. People always stop me and smile when I wear it,” she says.

Whether belonging to a client or jeweller, family heirlooms are, to use Maria Cristina’s words, “a memory that travels through time”. And memory really is the crowning value in an heirloom, says Sophia Hirsh. Take a silver band that her 13-year-old son, Henrik, made for her two years ago, and which she wears every day. “In terms of value, it’s my least valuable piece of jewellery. But in terms of sentimentality, it’s up there with my engagement ring, because Henrik made it.”

There’s also a “tiny” aquamarine ring inherited from her grandmother. “It’s very, very pale and not particularly valuable. But it means the world to me,” says Sophia. The ring was first given to Sophia’s grandmother by her grandfather when the two were 14 and 17 respectively. “They fell in love on a train and exchanged letters for years. When she turned 17, he gave her this as a promise ring, saying that the next one would be her engagement ring,” says Sophia. She wore it on her pinkie for years, and though it comes out less frequently these days, she’ll never transform it into a new gem.

“I feel it has to remain what it is. I still enjoy looking at it and get emotional when I do. I still have my grandmother – she’s 95 – and I think she’s quite happy to know that I look after it. I feel I’m just a custodian for another generation to come.”

Comments