Kehinde Wiley’s contemporary call to arms

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

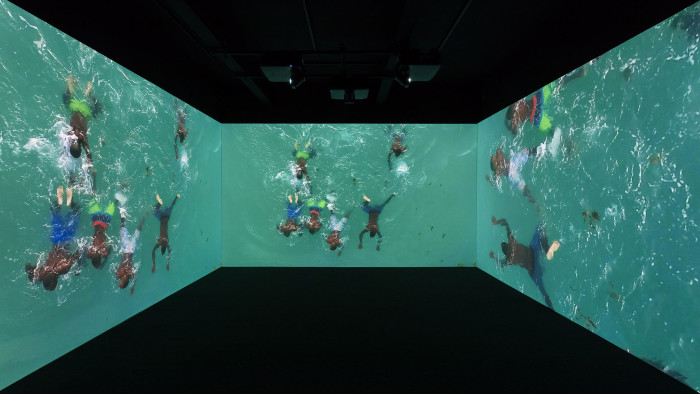

The sea feels different now. That is what I’m thinking as I watch Kehinde Wiley’s new film, Narrenschiff (2017), at Stephen Friedman’s London gallery. It’s set-up day so men are drifting in and out with cables, lights and sound equipment. Yet I am mesmerised by the triptych of moving images. There are human figures, chiefly young black men, who swim, run and gaze out to the horizon. There are boats — battered wooden vessels nearly as timeless as the water itself. But mainly there is the ocean: a vast, glimmering shape-shifter whose opaque skin remains as illegible as it is powerful.

Ten years ago, I might have read a seascape as a metaphor for inner peace. Today, the tsunami of images of imperilled refugees have cancelled out such a benign interpretation. Yet still there are moments when Wiley’s ocean exudes the contemplative mood of a chapel.

“It’s not about migration,” Wiley says when we settle on opposite sofas in the gallery. His unequivocal tones betray the sentiment of a man accustomed to over-simplifications of his work.

Now in his 40th year, primarily a painter rather than a film-maker, the Los Angeles-born Wiley is best known for portraits of black men — and some women — against backdrops of decorative, floral patterns or inserted into scenes echoing Old Masters such as Rubens and Velázquez. With wearying regularity, that oeuvre sees him reduced to a man on a mission to make blackness visible in a history of art that has ignored people of colour for centuries. Yet so elaborate and detailed are his paintings — each subject chosen with care, those patterns triggering lush, near-mystical associations — surely he is also expressing more complex truths?

“God bless you,” he breathes. “It’s so easy just to see the one-to-one narrative between presence and non-presence.” Beautifully dressed in burgundy jacket, pink shirt with monogrammed cuffs and jeans, in person Wiley is as immaculate as his paintings. His manner — soft-spoken, eager to listen as well as speak, and keen to engage with complex ideas even after a long day of press interviews — is equally disarming. Certainly, he has reasons for confidence. After a career which has included a significant US touring exhibition from 2015-17, plus a solo show at the Petit Palais in Paris, he has just been commissioned to paint the official portrait of Barack Obama.

Wiley prefers not to give bald explanations of his work. “I would rather just point. I never want to say ‘this is about that’.” Yet he does admit to “certain conceptual strategies”. Crucial, for example, is his analysis of desire. Historically portraiture has focused on women that are “sexually attractive to the male gaze”; Wiley hopes his paintings gesture towards a more “free-flowing desire”.

He wants to “remove the heteronormative dialogue” around which particular artists get to express desire and which subjects are made its prey. When he garbs his young male models as saints, heroes and leaders, he challenges a system that has fixed the black American male “within certain, two-dimensional, insufficient categories: hyper-sexuality, anti-social behaviour, a propensity towards sports”. Wiley observes, with admirable understatement, that such stereotypes are “to someone who occupies a black body strangely alien”.

Wiley is part of a generation of black men and women who are fighting their way out of these imprisoning fantasies. As such, there could be no better choice to paint Obama’s portrait. How does he feel about the commission?

“It’s a huge honour,” he says, his unalloyed happiness illustrative of his gift for sliding deftly from academic thought to a more immediate, emotional register. “To be the first black man in the history of the United States of America to create a presidential portrait [for] the National [Portrait] Gallery . . .” He lets the sentence evaporate to emphasise the quasi-miraculous state of affairs. “That’s humbling and breathtaking.”

As for details of the work itself, his lips are sealed. “I can’t talk about the commission itself until the portrait is done, but I can say I have shot numerous photographs and been in communication with [Obama] about how to create something really powerful.”

What he can talk about is the importance of “one man standing for the many”. Whether as statesperson, artist or portrait subject, the dearth of black figures in the public sphere sends a devastatingly discouraging message to young black citizens. “I remember the first time I went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and saw a Kerry James Marshall painting with black bodies in it on a museum wall . . .” He pauses, seeking the precise words. “It strengthened me on a cellular level.”

How old was he? “Oh, about 11 or 12.” Even then, green shoots of talent were flourishing. Born in south central Los Angeles, Wiley — a twin with four older siblings — did not know his father, a Nigerian who returned home after finishing his college studies in the US, though he subsequently developed a relationship with him.

Money was tight — his mother ran a thrift shop before qualifying as a teacher. But Wiley’s gift for art saw him, at the age of 11, join a non-profit programme providing arts classes to children. By then he had already absorbed the cornucopia of visual influences simmering within his mother’s store.

“We would see the insides of the houses of the black community,” he recalls now. “Hyper-decorative stuff! So many flowers on couches! It was kitsch; it was faux-rococo meets the black American street. No matter how informed I am around different aesthetics, [those images] left something in my DNA.”

Childhood memories flesh out not only the back-story to his fecund florals but also to his portraiture. Prefacing his words with the note that he “doesn’t often talk about this”, Wiley remembers that after winning a place at a conservatory — a weekend programme — as a gifted child, he found himself being “bussed into a white, wealthy LA neighbourhood” where he struggled with feelings of “competition, self-loathing and inadequacy”.

What saved him was his gift for making his classmates’ portraits. “If people looked at me like I was a little different I would maybe sit next to them and I would draw. And you know, it was a really cool way . . . you know . . . we would be friends.”

His stuttering syntax, so different from the smooth flow of his regular conversation, touchingly reveals his youthful anxiety. Portraiture, he continues, “was my shtick. It was my thing. It was both armour and sword.”

It’s possible that the elaborate costumes and settings bestowed on his models up until now reflect, on some level, Wiley’s desire to reinforce that vulnerable inner subject. (At one point, he tells me all portraiture has an element of “self-portraiture” within it.)

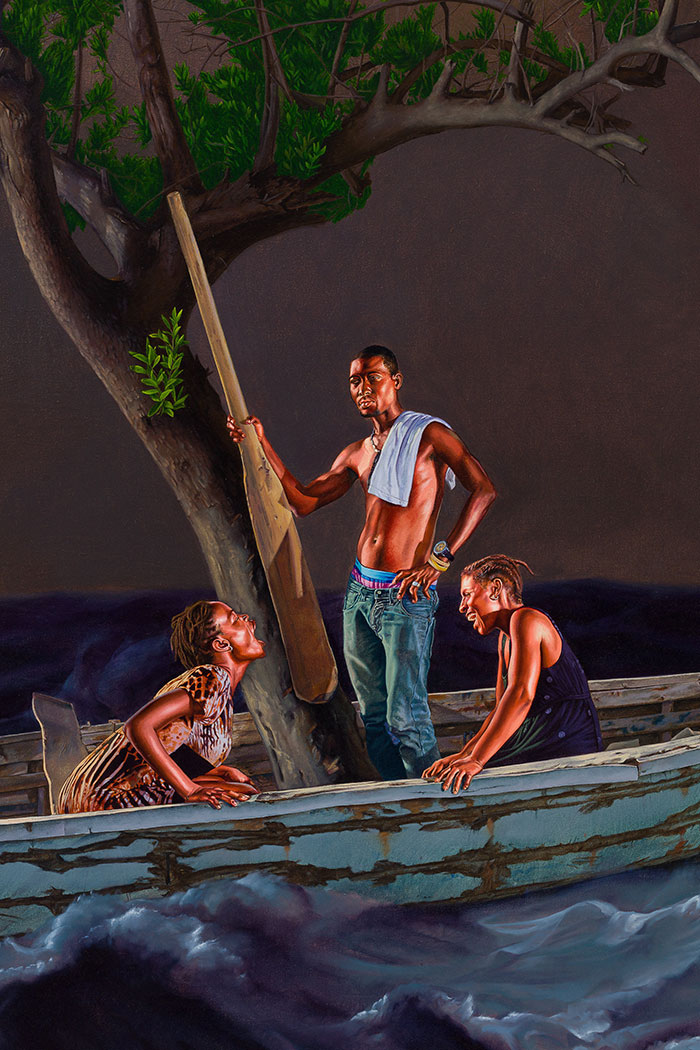

If that’s the case, then the figures in his new paintings are, interestingly, far less protected. Made to accompany the film Narrenschiff, the nine new works are variations on the tradition of historical maritime painting. Including nods to Turner, Winslow Homer and Hieronymus Bosch, these images range from tiny, desperate figures battling to stay afloat in wildly pitching seas to young black fishermen, dressed only in swimming trunks, planted on the shore whose mood of forlorn calm suggests that they are resigned to another working day lost to the inhospitable waves.

Wiley hopes that his audience will, like the young men, read such oceanic challenges as ultimately surmountable. “I am asking the question: is the sea friend or foe? My enduring hope is that the show chooses a partisan side. It is redemptive, not nihilistic . . . I stand on the shoulders of those who survived slavery and colonialism. Of those who created jazz, the blues and hip-hop from the most perilous situations.

“My work is a contemporary call to arms. It is time to get our mojo back. To rediscover our true north.”

Photographs: Mark Blower; Ana Cuba

Stephen Friedman gallery, London to January 27, and at Art Basel Miami Beach, December 7-10

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments