Planetary plea for help

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Polite chit-chat about the weather does not often spark an idea for an iconic art installation, but Lars Jan is more than a little preoccupied with the elements.

For his earlier work “Holoscenes”, individual performers going through everyday routines were repeatedly flooded by up to 15 tons of water inside their 13-foot transparent tanks. Set up in public spaces including New York’s Times Square and Exchange Square in the City of London, the simulated drowning while victims read a newspaper, sold fruit or tuned a guitar was intended to connect normal, familiar behaviour to the more abstract forces of climate change.

The idea for Jan’s latest public installation, “Slow-Moving Luminaries”, was sparked by a visit to Switzerland. Soon after winning the commission for this year’s Audemars Piguet pavilion at Art Basel in Miami Beach, the Los Angeles-based artist travelled to the watchmaker’s headquarters in Le Brassus. There, as he began to chat with the annual project’s curators for the first time, he suggested it must snow a lot there. “Yes — but a lot less than it used to,” he was told.

“Instantly I had a vision of a see-saw — a glacier goes down in one place and water goes up in another,” says Jan. “One is liquid and one is frozen . . . There is this mass and geographic separation but there’s a connectedness.”

Paired with Audemars Piguet’s light-touch framework for the commission of “complexity and precision” and the beachside location for the installation in Miami, a mechanism was set in motion to create “Slow-Moving Luminaries”.

Visitors will enter Jan’s pavilion on the ground floor, winding through a labyrinthine pathway surrounded by tropical plants. Minimalist model buildings, designed to resemble nearby hotels, will slowly fall from above then rise back into the ceiling. Go up the stairs to the next level, and the same stylised buildings will emerge through a shallow rooftop pool, merging into the Miami skyline behind them.

Beneath the pool, lines tracing the path of the labyrinth below will spell out “SOS”. This planetary plea for help is only visible to those flying above it — helicopters that are able to flee the rising seas or, perhaps, aliens coming to the rescue, suggests Jan. Square and circular windows around the pavilion are also intended to recall the shapes of the maritime “SOS” distress flag.

Jan was born in a small coastal town outside Boston where, he recalls, his basement would often be flooded. “There is something very visceral about water,” he says. “That’s an important part of the [Miami] project, that it’s not just conceptual and aestheticised. There is something about moving water, sinking, that gets me personally in my gut.”

Yet “Slow-Moving Luminaries” is not as bleak as its recollection of sea-level rise might suggest. “Because it’s so heartbreakingly beautiful and seductive, and it’s an experience that in a way you’re surrendering to, you are encouraged to look a little harder and stay a little longer,” says Kathleen Forde, curator of the project for Audemars Piguet.

Jan has spent time living in Kyoto and the Miami pavilion is intended to be a meditative place, like a Japanese temple. Walking around that “SOS” shape, even if visitors do not realise they are doing it, is key to that. Jan says he is invoking a tradition in Celtic Christianity, where worshippers would walk the shape of the cross.

“So it’s a walking meditation,” he says. “There is an inherent geometry to the pathway that you’re kind of retracing over and over again, that is supposed to inform your thinking. So that’s one of the ideas that inspired tracing the SOS — that we’re walking through space, we are looking at the world from different perspectives but there’s a kind of unconscious physical resonance.”

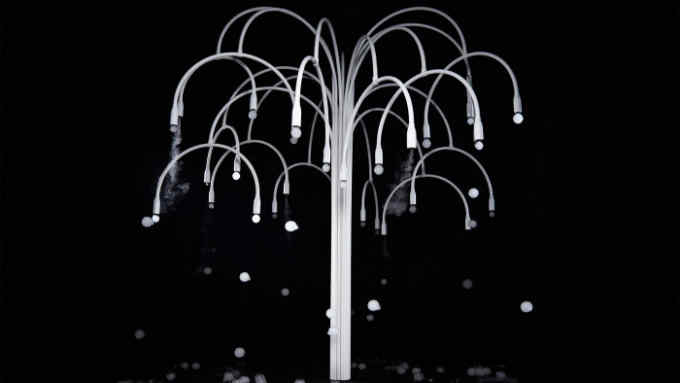

The buildings that float around visitors as they walk are synchronised so that once every hour, all five rise and fall together. Before visiting Le Brassus, Jan says, “I had never considered the extent to which timekeeping — and especially the tiny mechanism in a watch — is kind of an imperfect approximation of the movements of these massive celestial bodies, the earth and the moon. In antiquarian terms, luminaries are the sun and the moon, which are definitive of how we perceive time and the movements of our lives.”

That is just one way to read the work’s title, though. “Luminaries” might also refer to our role models or thought leaders, many of whom have been slow to respond to the crisis of climate change. On a more literal level, the buildings are illuminated objects.

“There is an algorithmic logic determining the rhythm of the five buildings,” says Jan. “So you’re seeing all of these sort of sunrises and sunsets, yet they are mechanised in an algorithmic pattern . . . There’s a kind of kinetic mechanism to the entire installation.”

Finally, the audience themselves are in some way the luminaries too. “The audience are moving slowly through because they are in a labyrinth, they perform the piece. It completes the work,” says Forde, who also serves as artistic director at large for Borusan Contemporary in Istanbul.

Any or all of these interpretations are up for grabs, as Jan prefers not to impose any one specific message on the viewer. “One of the things that is so nice about Lars’ work is that it has an open-endedness — that space to take your own perspective,” she says. “If Lars is providing one particular answer for what the installation means, the conversation stops.”

Even so, climate change is likely to be in the minds of many visitors: not only because of the pavilion itself, but its situation. In September, Miami was hit by strong winds and rains from Hurricane Irma, uprooting trees and causing power outages lasting for days.

“Coastal Florida is really the tip of the spear in terms of feeling the effects of sea level rise and climate change right now,” says Jan. “The thing that I’m most interested in is the fragility of our structures and our existence on the precipice of this great natural body, which is the ocean.”

Although the global issues that these works tackle may seem vast and insoluble, Jan hopes that the kinetic, multi-faceted “Slow-Moving Luminaries” will also connect with people on an individual level.

“The way that we think about our lives in relationship to time, I think, is a deeper problem,” he says. “We are moving ever faster, not just in terms of attention span but in terms of the shifts in our desires. The rhythm at which we are moving and making decisions and even thinking is a bigger issue than any of the other issues that face us.”

Photographs: Audemars Piguet

From December 5, audemarspiguet.com/en/experience/art-commission

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments