Ukraine seeks billion dollar investments to fuel fragile economy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ukraine’s prime minister Volodymyr Groysman quickly took advantage of becoming involved in a Twitter exchange in which technology entrepreneur Elon Musk boasted that his lithium-ion battery technology could prevent electricity blackouts in Australia.

Mr Groysman tweeted swiftly back: “Interesting idea. Ukraine is eager to become a test site for innovation. Let’s talk it over in detail.” Formal discussions followed, the prime minister told the Financial Times, in an interview in which he praised Mr Musk’s “experience and capabilities”.

Such opportunities of direct contact with influential global businessmen are not to be missed. Ukraine desperately needs billion-dollar investments to fuel a fragile economic recovery as it presses on with difficult — and at times patchy — reforms of the former Soviet republic’s economy and government institutions.

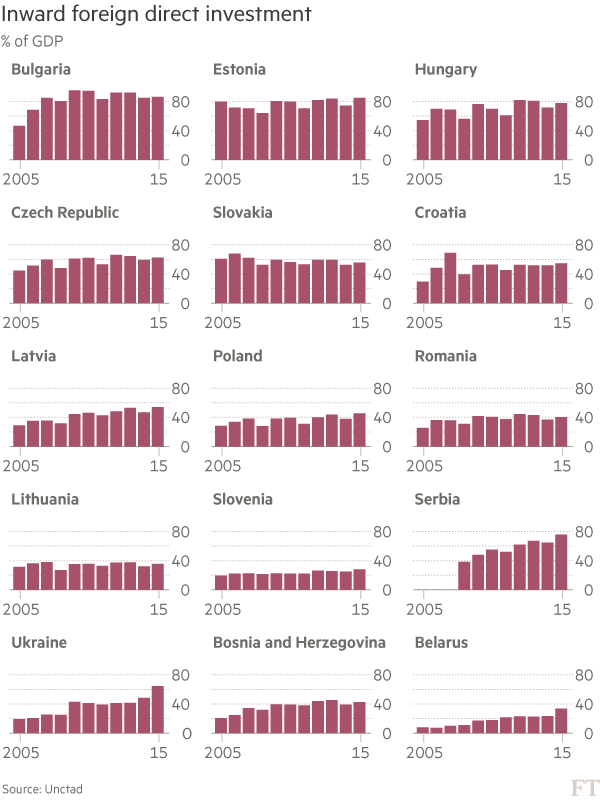

Recapitalisation of shaky banks accounts for most of a paltry $3bn in net foreign direct investment lured in 2016. The country last year crawled out of recession posting 2.3 per cent growth in GDP following a contraction of nearly 17 per cent over the two previous years.

That followed Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and the fomenting of a proxy separatist war in far eastern regions that continues to claim lives and sap financial resources.

Yet despite turmoil in these hotspots, Mr Groysman is keen to convey the message that 90 per cent of the country is safe and open for business.

“We cancelled more than 3,000 . . . regulations, which were the basis of corruption and pressure upon businesses,” he says. Changes include more transparent refunding of VAT to exporters through a new automatic online registry, reform of the natural gas market and the introduction of a business ombudsman.

The latter provides a forum for the business community to file complaints about unjust treatment by the state or municipal authorities, state-owned or controlled companies, or their officials.

Reforms to the gas market, meanwhile, have not only wiped out the country’s once heavy dependence on Russian fuel imports, but also opened to foreign traders a multi-billion-dollar sector once solely set aside for domestic oligarchs. It is one of the government’s initiatives that is starting to bring in foreign business. Since last month it has allowed foreign traders to bid for contracts to supply the national pipeline operator with gas for the first time.

ProZorro, Ukraine’s attempt to introduce a more transparent electronic procurement platform, has replaced old paper-based state tenders.

Before ProZorro “you needed to be the prime minister or above” to deal in gas domestically, but “now it’s an open market”, says Andrew Favorov, managing director of Energy Resources of Ukraine (ERU), one of the winning bidders, who cites the presence of Trafigura and Engie.

ERU has started to supply gas to restart the strategic state-owned Odessa Port chemical plant, delivering up to 60m cubic metres of natural gas per month in exchange for ammonia and urea, which ERU will turn into fertiliser for local and foreign markets. The project is backed by various EU suppliers with risk insurance provided by the US government’s Overseas Private Investment Corporation.

Mr Favorov adds that ERU is considering options to purchase the Odessa Port Plant, the largest of Ukraine’s chemical plants, which remains plagued by debts after two attempts to privatise it last year flopped due to lack of bids.

An upbeat mood was reflected by another investor betting on Ukraine. EuroCape New Energy plans to start building a nearly $1bn, 500 megawatt wind power array this year close to Crimea and eastern front line regions where Russian-backed separatists battle against government troops daily.

“You can make money here,” says Peter O’Brien, EuroCape’s country manager. Electricity market amendments, also adopted in April to boost competition, are a “game changer” that will connect the Ukrainian and EU electricity grids, setting the stage for lucrative power exports, he adds.

Opportunities range from banking and energy to agriculture and the automotive supply chain. Keen to capitalise on low-cost labour, manufacturers from Japan and EU markets have stepped up production in western Ukraine, turning the region into a part of Europe’s vehicle industry.

Investors from as far as China are eyeing construction of solar power stations in the exclusion zone around the decommissioned Chernobyl nuclear power plant, site of the world’s worst nuclear accident in 1986.

An overhaul of the healthcare system this year promises to slash financing of state hospitals by introducing a system where reimbursement for care “follows the patient”. This is likely to shift patient treatment, and investment, to private clinics.

And after nearly half of Ukraine’s 180 banks were shut down since 2014 as part of a sector “clean up”, their assets, including credit portfolios and branch offices, are to be auctioned.

“Scores of distressed assets are seeking investment,” said Tomas Fiala, chief executive of Kiev-based Dragon Capital. The group’s private equity fund purchased a dilapidated mall in a “great location”, even though it complains of harassment by the authorities and is in a legal dispute to regain its stake in another mall.

Toronto native Daniel Bilak, adviser to Mr Groysman and head of UkraineInvest promotion agency, acknowledges that investors have lingering complaints about corruption, unruly courts and a lack of respect for property rights. But he points to judicial reforms, including wider public participation in the selection of judges, which aim — over the course of years — to improve trust in the legal system. “The country is really transforming,” he says.

Addressing a gathering last month organised by the US-Ukraine Business Council, Francis Malige, regional director for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, said his institution was keen to lend more to the country.

The EBRD, Ukraine’s largest financial investor, has commended the authorities for achieving more in reforms in past three years than in prior decades. But Mr Malige warned that larger investment inflows would not arrive until key problems — such as foreigners’ inability to repatriate dividends and a long-stalled start to privatisation — are addressed.

Putting thousands of poorly managed state enterprises into private hands remains “for now a complete failure” but is potentially “a great way to put Ukraine on the map”, Mr Malige added.

Mr Groysman has pledged to start this year with auctions of alcohol distilleries, seaports and utilities.

When asked whether Mr Musk provided a definitive answer on investing, the premier says simply that he is “awaiting a response”.

The article has been amended that the worst nuclear accident was in 1986 not 1996.

Comments