Political and ethnic tensions fuel fears of east-west split in EU

Simply sign up to the EU economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It became a commonplace to observe that Europe was uncoupling along north-south lines during the most intense phase of the eurozone crisis, from the first half of 2010 to the second half of 2012. At one end, it was said, were Germany and other wealthy, fiscally prudent northern European creditors. At the other end, lay Greece and other vulnerable southern European debtors.

These categories were too simplistic. Slovakia, for example, was a staunch ally of Berlin in the eurozone’s divisive bailout discussions. But Slovakia was, and is, neither northern European nor as affluent as Germany. For its part, Ireland ended up in the financial emergency ward next to Cyprus, Greece and Portugal — even though culturally and geographically, it is no Mediterranean nation.

Few EU policymakers appreciated at the time that only a few years later, the problem that would preoccupy them would be the danger of a rupture in Europe, not between north and south, but between west and east. In contrast to the earlier perceived split, this emerging division is not about budgetary rigour, broken banking systems, economic stagnation, clientelism and corruption. It is about democracy, the rule of law and attitudes to migration, Islam, national sovereignty and European unity.

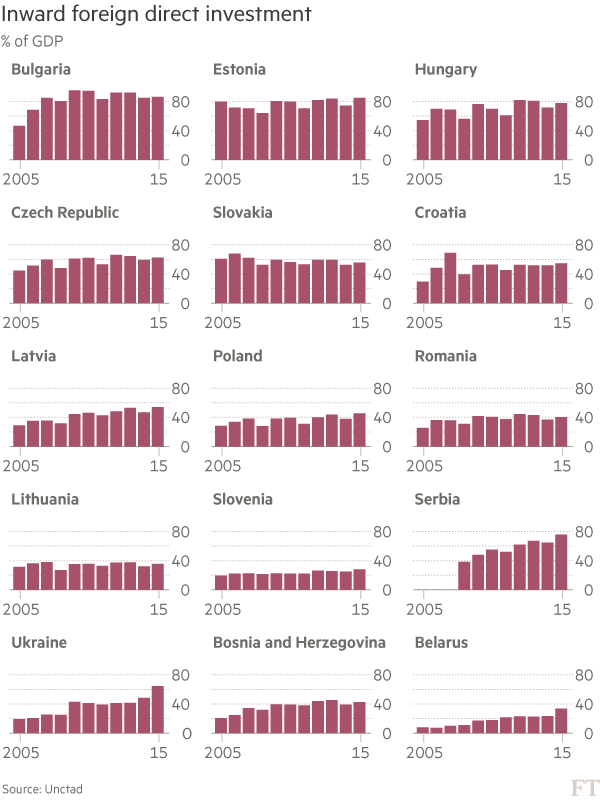

If unchecked, this rupture risks evolving into a mortal threat to the EU’s integrity. It is a disruptive political and cultural factor which, for years to come, will shape investment risks in central and eastern Europe. At present, foreign direct investment in the region is relatively buoyant. However, investors from China, the Gulf states, the US and beyond should never lose sight of the fact that any developments pointing towards the separation of eastern from western Europe will tend to their disadvantage. The region’s long-term economic strength depends on integration with Germany and other advanced western European economies

As with the north-south split, the east-west division is a loose concept rather than a statement of strict geographical fact. Among EU member states, Hungary and Poland are the countries about which western European governments exhibit most concern with regard to standards of democracy, protection of human rights and impartial administration of the law. By contrast, there are few such worries about the three Baltic states, which lie to the north-east.

Outside the EU, western concerns range from political instability and ethnic tensions in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and Macedonia to a potential drift towards strongman rule in Serbia after the April 2 presidential election victory of Aleksandar Vucic, a former radical nationalist who has served as prime minister since 2014. Western European governments are also apprehensive about the impact on the Balkans of Russian encroachment and frictions with an increasingly undemocratic Turkey.

As for Europe’s migrant and refugee emergency, and the related matter of official attitudes to Muslims, one sore point for Germany, Sweden and other liberal western European nations is the hardline stance of the Visegrad Four — the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia — against EU-proposed quotas for resettling refugees. In particular, the tendency of some Visegrad leaders to depict Muslim refugees and immigrants as a civilisational threat to Christian Europe goes down exceptionally badly in much of western Europe.

Investors should be aware of these developments, not simply because well-governed societies with tolerant political cultures and reliable legal systems are inherently better places to invest over the long term. They should do so because the economic vitality and political health of central and eastern Europe is inextricably bound up with the region’s EU membership — or, for some Balkan countries, with the prospect of membership in the future.

To reap the highest rewards from their investments, outsiders need the region to be close to the heart of the EU economy and harmoniously integrated into the bloc’s political and legal structures. They need its companies, workforces, rules of business, and energy and transport networks to form a seamless whole with the rest of the EU.

The growing risk today is that, as western European governments discuss options for a “multispeed Europe” and contemplate delaying the next round of EU enlargement, some parts of central and eastern Europe will find themselves left behind. This concern is especially acute in non-eurozone countries, such as Hungary, Poland and Romania, and countries that fear their chances of joining the EU may never come, such as Albania.

Consider the region’s concerns against the backdrop of the eurozone crisis. That episode provided good and bad lessons for the EU. Perhaps the most encouraging lesson was that, although it took time and money to recapitalise stricken banks and return impaired government budgets to balance, Europe’s leaders were ready to draw on great reserves of patience in order to keep financially damaged nations, even Greece during its erratic behaviour in 2015, in the family of EU nations.

However, there is no guarantee that, if push came to shove, western Europe would show identical patience towards any central and eastern European countries that kept drifting away from EU norms of political freedom, the rule of law and solidarity in the face of common challenges such as the migrant crisis.

Countries like France and Belgium are already displaying impatience with events in certain states to the east. The more such disagreements persist, the higher the risk that one or more central and eastern European states will one day occupy a second-tier place in the EU club. This would damage Europe and is the point that investors need to keep in mind.

Comments