Minister seeks to steer Slovakia past a ‘lasagne of evil’

Simply sign up to the European companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Of all the images used to describe the populist wave sweeping Europe at the moment, Peter Kazimir has perhaps concocted the strangest: the lasagne of evil.

Each layer of the lasagne, Slovakia’s finance minister explains, represents a different part of society that has failed to curb the swelling unrest — the media, politicians, corporations, even religion.

“Now we have to eat it,” he says, pointing to Britain’s impending departure from the EU, but with an eye on the rising poll numbers for far-right parties from France to Hungary to Greece.

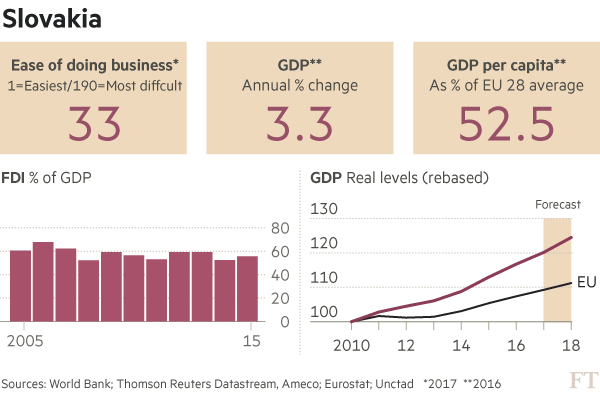

This unpleasant gastronomic comparison does not sour his outlook for Slovakia. The former Soviet-dominated nation that joined the EU in 2004 and embraced the euro in 2009, is establishing itself as one of central Europe’s industrial powerhouses.

The country, fresh from elections last year that saw the ruling Smer-SD party reinstated as part of a three-party coalition, has good reason to be optimistic about the future. Its economy is forecast to grow at 3.3 per cent this year, unemployment has almost halved over four years to 8 per cent, and its budget deficit, already among the lowest in the EU, is expected to be eliminated by 2019.

We meet at Mr Kazimir’s office in Bratislava, also attended by his labrador dog, Rafael.

Foreign investment, from Jaguar Land Rover to Amazon, is pouring into the country, says the 48-year-old minister, who until last year also held the post of deputy prime minister.

Yet Mr Kazimir, though bullish, is concerned about the wealth gap that exists between the prosperous western regions and the poorer east. “The biggest problem of this country is regional disparity,” he says. While unemployment is low around the capital, it rises to as high as 20 per cent in some eastern regions.

Mr Kazimir, who describes his birthplace of Kosice in the east of the country as “a city in the middle of nowhere”, says there is a serious need to improve mobility of the potential workforce in the east to the job-rich west. Many new vacancies are being created, notably in the country’s growing automotive sector, which already supports 200,000 jobs. But they are broadly in the west.

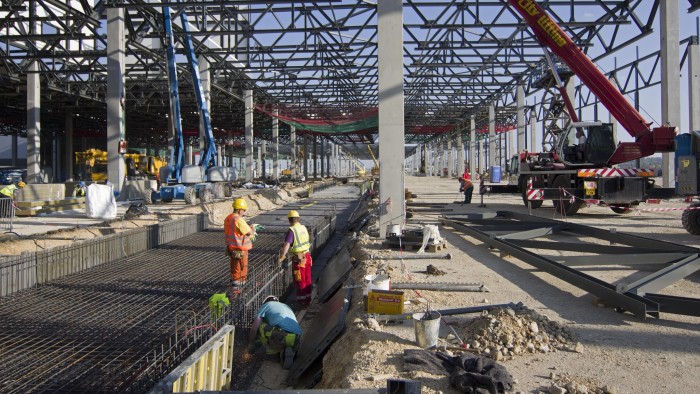

He was part of the team that secured the investment of Jaguar Land Rover in a £1bn plant, beating off stiff competition from neighbouring Poland and far-flung rivals such as Mexico.

The British carmaker’s operation is based just outside Nitra, less than an hour’s drive from the capital. Because many of the parts for its cars will come from Germany or the UK, the government could not persuade the company to move any further east.

“More eastern was less attractive for them,” says Mr Kazimir. “Every kilometre is important.”

Volkswagen, which runs a large car facility in Slovakia making vehicles for the VW, Audi, Porsche, Skoda and SEAT brands, is expanding, as is Peugeot’s plant. Both are also in the west.

To try and improve mobility, the government is proposing a measure to encourage Slovaks to rent property. “Renting is very rare — 85 per cent of real estate is in the hands of individual owners,” Mr Kazimir says, adding: “These people are not mobile.”

Further down the road, the government has a more ambitious scheme to revitalise the east — by wooing the investment might of China.

Mr Kazimir was recently in Chongqing, south-west China, to see the logistics hub that is one end of a railway that links the People’s Republic to Germany with a line that passes through Russia, Belarus and Poland as part of a New Silk Road designed to increase trade between China and Europe.

“They can deliver goods from China to western Europe in just 18 days,” he says, obviously impressed. “Connection with China’s market is crucial, and this can be decisive for the Eastern part of Slovakia.”

It is not the only large international project the government is hoping to attract: Slovakia has signed a memorandum of understanding with one of the companies developing hyperloop technology — a futuristic travel mode in which levitating pods zoom through a vacuum tube at breakneck speed. A scheme envisages a test tube that would run to Vienna, less than an hour’s drive over the Austrian border.

The government also wants to set up areas to test self-driving cars and attract foreign companies such as Tesla to use the nation’s roads as a proving ground for some of their features.

Others, such as Hewlett-Packard, are setting up in Kosice. But despite the investment from outside the country, precious little technology is developed within Slovakia’s borders. He points to flying car start-up AeroMobil as a pioneer of Slovak-developed technology, but it is the exception to the rule. The research and development that goes into the country’s cars takes place in the home nations of Volkswagen, Peugeot, JLR and Kia. Out of the 40 largest automotive supply chain companies, only two are Slovakian.

The country’s biggest selling point — its low labour costs — works wonders to incentivise companies to bang large pieces of metal together there, but does little to convince them to locate researchers to the country. “We would like to focus on this,” says Mr Kazimir.

So, might Britain’s impending departure from the EU be a chance for the country? He admits there will be competition among some nations to host banks or UK-based agencies, but stresses that Brexit is not “an opportunity process” for Slovakia.

Nor will the process hurt Slovakia, insists Mr Kazimir, even though many of the cars made in the nation are sold to the UK. But that does not mean it will not be painless for the EU as a whole. “I expect that it will be quite a bloody exercise for both sides,” he says. “That is my feeling.”

Slovakia and the Czech Republic enjoyed a peaceful divorce following the collapse of the Soviet bloc, he says, but even then the beginning of the process was difficult. Brexit may be harder, though.

“We were poor,” he says. “For rich people it is always very difficult to divorce, and this is the situation of the UK and the European Union.”

Mr Kazimir, a long-time critic of the EU’s handling of the Greek crisis, is almost dismissive of the bloc’s ability to learn the lessons of history when it comes to tackling sensitive negotiations.

There is, he says, still bitter feeling at the top echelons of the European Union about the outcome of Britain’s vote last summer to exit the EU.

“You still have high-ranking political personalities in Europe, these godfathers of Europe, who believe in the European idea, and they feel they were betrayed.” His voice lifts at the end of the sentence, in a questioning tone as though he has picked the wrong word, and glances over to his adviser. “Yes,” he continues, “betrayed.”

Comments