From dandies to cruising, Art Basel talks probe life in Paris today

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Outside, traffic speeds by, the 21st century is in full swing, but within this Montparnasse brasserie the talk is of dandies, decadence and nocturnal trawling in search of sex: another normal day for curators Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou.

The pair have been picked by Art Basel to run the conversations programme at its new fair, Paris+, which opens next week, and their proposal defied the often anodyne themes of such events, with talks on matters such as curating “dangerous” collections; raving, hedonism and protest; and Pan-Africanism in countercultures.

One talk is particularly close to their hearts, centred around the legacy of the dandy, that elusive, glamorous, slightly sulphurous figure who has been an important part of their curatorial work. The dandy first emerged in Paris and London of the 1790s as a vain character who paid more attention to his clothes than to politics or culture.

But he (and it was most often a he) fascinates the pair not because of his sartorial inclinations but because he is a master of self-creation, says Mateos: “The dandy is a celebration of imagination and a certain sense of theatricality. You can come from a working-class background and invent something completely different with your look. [They have] the capacity to reinvent, to create an avatar . . . to invent your own category.”

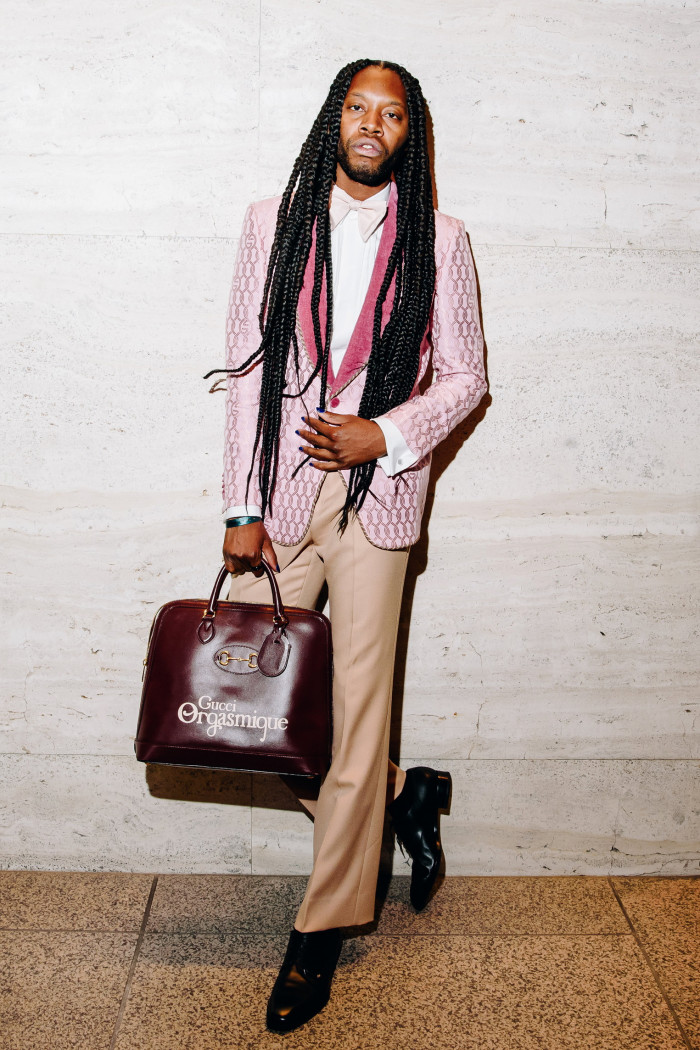

They are bringing the dandy to Paris+ because they see a strong strand of dandyism in artists, who are always reinventing themselves against bourgeois society. But the dandy of 2022 can be of any gender, race or culture, as long as they’re defying society’s binaries and received wisdom. One of today’s foremost dandies, the black American playwright Jeremy O Harris, is due to appear in the Paris+ talk.

While we might once have considered the dandy work-shy, their soft hands unsullied by labour, this same quality makes them distinctly modern figures in a productivity-obsessed society, says Mateos. “A dandy is revolutionary — his pose is a kind of passivity in a world which is always pushing you to produce produce produce.” Beau Brummell: anti-capitalist.

But this passivity — the dandy is “someone who doesn’t transform his thought into opinions, transform his thought into statement”, says Teyssou — is dangerous: disengagement from society leaves the field to radicals. (It can also tend to a fatal “black romanticism”, says Mateos.) It’s here we might distinguish the dandy and the artist, since artists are perpetually productive and always reifying their thoughts.

Leaving behind the distant, dissolute dandy, a second figure of fascination for Mateos and Teyssou appears in another Paris+ talk: the man cruising for sex. This might seem an unlikely topic for an art fair, but the pair want to look at how art and desire — both powerful creative drives — intersect and can even be indistinguishable. There are many examples of art and cruising crossing paths: take Manhattan’s desolate piers in the late 1970s, which people visited to seek sex, make art or both (like David Wojnarowicz).

Cruising also has its own aesthetic effect, they argue: it changes the way we understand our cities and allows us to see familiar spaces — in Paris, the Tuileries garden is known as a cruising spot — in a new light. City-centre monuments become “poetic” utopian cruising sites, says Teyssou, uniting people from different backgrounds with a common aim. Cruising itself, says Mateos, has “this capacity to re-enchant, to make luminous and magical and to reinject a sense of desire into what seems hollow, dead”.

The Paris of both dandies and hook-up spots is certainly enjoying its moment in the artistic spotlight, with large foundations and institutions opening in recent years (Fondation Louis Vuitton, Bourse de Commerce) and galleries arriving from abroad, such as Chicago’s Mariane Ibrahim. So is Paris changing from the city which “nurtured an ad nauseam obsession with its own reflection”, as the duo have written, into something more open, outward and diverse?

Mateos agrees, ascribing the belated evolution of local countercultures to “the blooming of Paris [thanks to] art and other [creative] industries”. Paris’s music scene is “very vivid right now” too, because its west African roots and communities are growing in prominence and confidence. But Teyssou thinks there is more to it than the culture industry: “There is also a part which is a bit mythological — you never know quite why it’s happened. There is this kind of feeling that Paris is at the centre again and everyone wants to rush in, but nobody knows why.”

The Paris+ talks programme runs October 20-22, parisplus.artbasel.com

Comments