Prune Nourry is super-sizing her sculptures

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

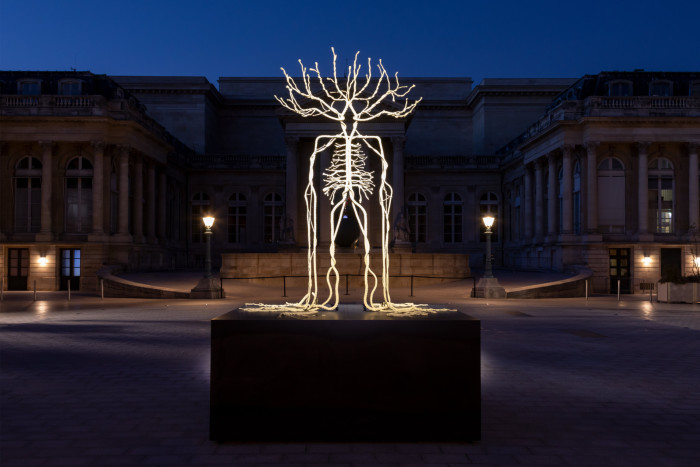

When Prune Nourry was seven, she saw a giant statue of the Buddha on a family holiday in Sri Lanka. It clearly left a lasting impression, judging by the 37-year-old French artist’s tendency to work at extraordinary scale. In 2018, she placed a four-metre-tall Amazonian warrior-woman outside the Standard Hotel in New York. At the start of October, she installed “Atys #1”, a three-metre work in bronze, in the Cour d’Honneur of the Palais Bourbon in Paris. Inspired by a character in a Baroque ballet by Lully, for three months its stark, spiky silhouette — half-man, half-tree — will stand in front of the building where the lower house of the French parliament meets. Perhaps those inside will consider more carefully the relationship between man and nature as a result.

But on October 15, a work will be revealed that has taken Nourry beyond even her own gargantuan limits. At Château La Coste, the exquisite sculpture park in the south of France with works by more than 40 artists, visitors will be able to walk on, around and inside a huge figure of a pregnant woman fashioned from clay, called “Mater Earth”. At 27 metres long and 13 metres wide in parts, the sculpture appears to be half-buried in the Luberon soil. “As we grow up, we lose our sense of wonderment, our inner child,” says Nourry, “and I think scale can bring some of that back.”

For her, this vast and apparently fecund woman may mean many things, though she prefers to leave interpretation to the viewer. As a younger artist, she had often explored ideas in her work about genetic manipulation and in vitro fertilisation. Once she devised a “procreative” dinner party which delivered the parts of conception one by one in edible form — from risotto embryos to pannacotta breasts. She created a Sperm Bar in New York in 2011, converting a food truck into a drinks van where the characteristics (hair colour, educational level, hobbies etc) of your “dream” donor determined the cocktail you were given. (That same week, it was announced that US sperm donor banks were no longer taking contributions from redheads for the foreseeable future.)

Then, in 2016, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which put her at the centre of a conversation in which she had previously taken an anthropological position; the woman who had made artworks about bioethics had to decide whether to harvest and freeze some of her own eggs. “When cancer came along,” she says, “it reminded me that an artist is never objective.”

I watched “Mater Earth” taking shape earlier this year on a searing summer’s afternoon as Nourry’s two-and-a-half-year-old son was being looked after by her mother elsewhere in the Château’s sprawling grounds. She was wearing a wide-brimmed black hat that she’d bought at another site for art pilgrims, Marfa in Texas; it was essential to keep off the relentless rays of the sun as she carried out the physical labour her work required.

The sculpture seemed to be a celebration of the artist’s own ability to bear a child and the broader power of procreation, while the work involved felt like an act of catharsis. Nourry was sculpting the breasts, slapping on massive handfuls of local clay and working it into shape. She had previously made 4,800 clay bricks to line the woman’s womb. When we sat down to have something to eat, she offered me a feel of her rock-hard bicep. It felt like the bicep of a woman who’s working away pain.

Nourry isn’t afraid to talk about her cancer. She has even made a film, Serendipity, which shows her undergoing hospital treatment, being rolled down corridors on a gurney, interspersed with stories about her artworks. It’s an unconventional self-portrait. At one point, the film director Agnès Varda appears and cuts off a long braid of the artist’s hair, anticipating the effects of chemotherapy. “It wasn’t meant to be in the film. But Agnès is a friend and said that she had marked her transition from girl to womanhood by doing the same thing. She made the camera roll,” says Nourry. When the chemo takes hold, she shaves her head on camera. Despite appearances, though, “It was very hard to do. I’m a very private person.”

Indeed she can be. Nourry prefers to be photographed with objects in front of her face, and will not be drawn on the subject of her partner, the street artist JR. Yet she has turned the camera on herself and often works in public — most recently in an open studio in Nigeria, where people could wander in and out — and also at this attention-grabbing scale.

For the Nigerian project, she travelled to the city of Ife in the country’s south, which has a virtuosic tradition of clay sculpture going back centuries. With a team of 108 art students from the University of Ife, Nourry made 108 heads — inspired by 15th-century Ife heads — to remember the missing girls detained by Boko Haram. (They were kidnapped in 2014.) “The Yoruba people believe that a sculpture has a soul,” she says.

She is hopeful that “Mater Earth” will develop one too. Visitors can gain access to a cavity in her belly by ducking through a door just 130cm high. “It’s like entering the veiny inside of an organ, or a mass of tree roots, like mangrove,” says Nourry of what lies within. She wants visitors to feel a sense of rebirth on re-emerging into the sunlight. “It’s inspired by the temazcals you find in Mexico. They are domes made of clay, and inside volcanic stones are heated by fire, and steam is made by water. You sit there and sweat and when you come out, bending down to leave, you feel reborn,” she says. “I like to think she will absorb the life and energy of everyone who enters her.”

While many of Nourry’s projects are temporary or mobile — the Amazon has left New York and is in storage in Greece where it will appear in a film project; the Nigerian heads tour the world — “Mater Earth” is here to stay. “I love to think of a child coming back as an adult,” she says. “Or it might inspire some wonder in a kid — like the Buddha did for me when I was seven.”

Comments