Why Marine Le Pen is the choice of ‘unhappy France’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Marine Le Pen’s National Front party has tapped into new and diverse layers of the electorate and become the choice of “unhappy France”.

A new paper from Sciences Po and Cepremap, shared with the Financial Times, shows a clear division between a “pessimist” France turned towards Ms Le Pen, and an “optimist” France embodied in Emmanuel Macron, the centrist candidate who has never previously stood for office.

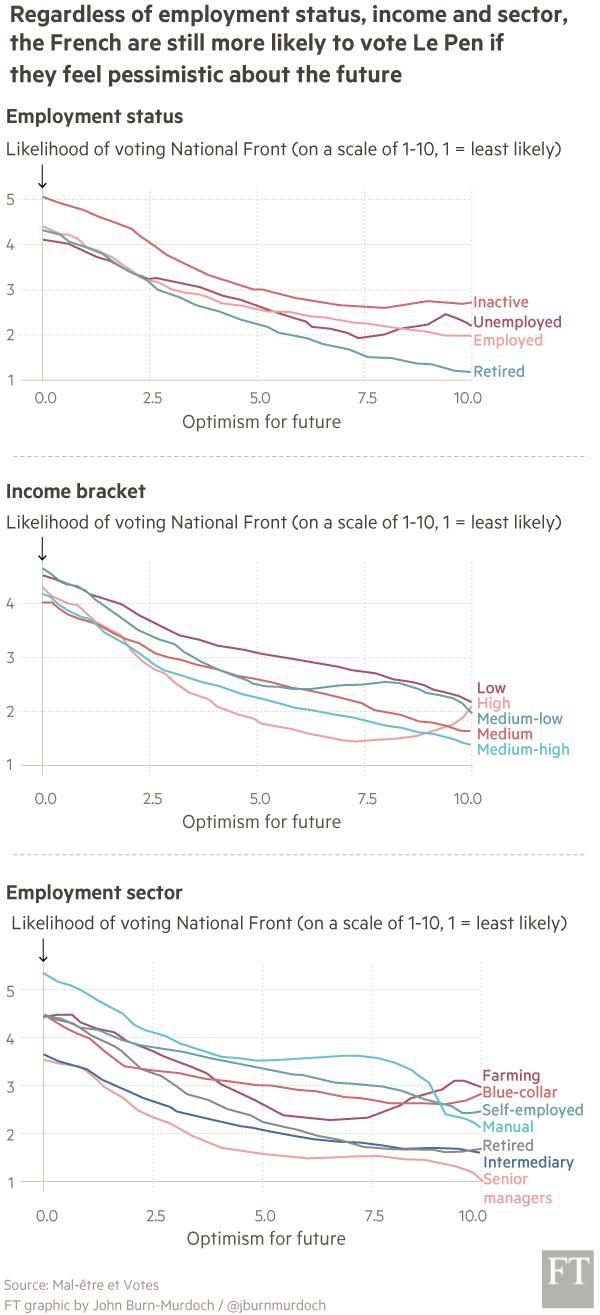

According to the research, a sense of deteriorating wellbeing is one of the main explanations for rising support for the FN in Sunday’s first round of the French presidential election, cutting across most boundaries of age, education or economic status and sapping support for mainstream parties.

When asked* about their expectations for the future, the individuals who were most pessimistic were those most likely to vote for Ms Le Pen or Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the far-left candidate whose support has risen sharply in recent weeks. In contrast, those most satisfied with their life opted most often for Mr Macron, followed by François Fillon and Benoît Hamon, the candidates of the traditional centre-right and centre-left parties.

Anxious society

The researchers explain this link between well-being and an intention to vote for the FN as a “crisis of hope”, saying that after almost 10 years of financial crisis, many people — well beyond the working and middle class — have lost hope of a better future.

“We tend to think that only poorer and less educated people lose because of globalisation. It is not always true — those with higher education also often have to take their chances in very competitive sectors and they do not always succeed,” says Martial Foucault, head of Centre de Recherches Politiques de Sciences Po and co-author of the paper. “Marine Le Pen says: ‘I am going to protect you,’ and they are convinced that she will.”

The feeling of being left behind is present in people from very different backgrounds. Age, income, employment status and level of education do remain relevant but are less important to voting intentions than how gloomy one is about one’s future, according to the data.

Importance of education

Educational attainment proved significant in the UK’s EU referendum, the US presidential race and the recent Dutch election. In all these votes, it was the less educated who tended to choose the “populist” option — whether voting to leave the EU in Britain or for Geert Wilders, the Dutch anti-Islam politician.

In France, similarly, the likelihood of voting FN decreases as a voter’s education increases. However, the Sciences Po research shows that the level of education becomes less of a factor if a voter’s outlook for the future is pessimistic. The trend is particularly visible among older voters (over 50), where a more optimistic outlook quickly reduces the likelihood of voting for the FN. Younger people’s voting intentions seem less affected by pessimism.

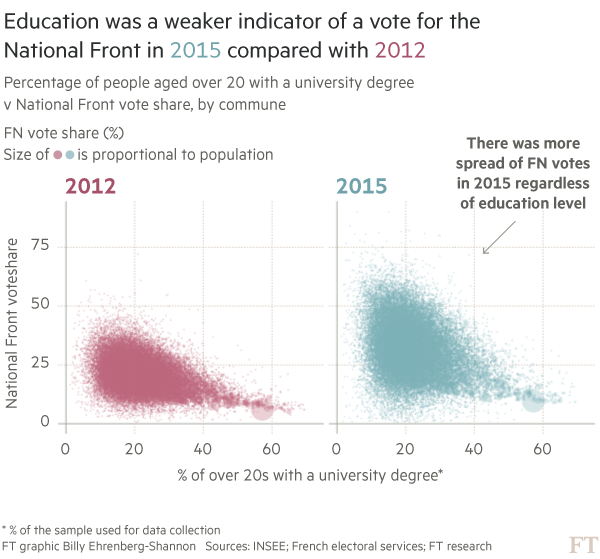

The findings have been backed up by the Financial Times’ own analysis of educational attainment and the FN vote in two recent French polls: the 2012 presidential vote and the 2015 regional elections.

Although the two elections are not directly comparable, the 2015 regional elections were the last before the current presidential race, and also the ones where the FN won its highest share of votes. The FT followed in the steps of the researchers at Sciences Po and examined FN supporters’ socio-demographic characteristics.

In the FT’s analysis, which covered those aged over 20, education — the percentage of people with a university degree — explained less of the vote for Ms Le Pen in 2015 than it did in 2012. This could indicate the FN is gaining ground among voters with higher educational attainment.

Education is a proxy for many other social factors, however, which may have influenced how long a person stays in education. It is a mix of these factors that ultimately influences who a voter chooses.

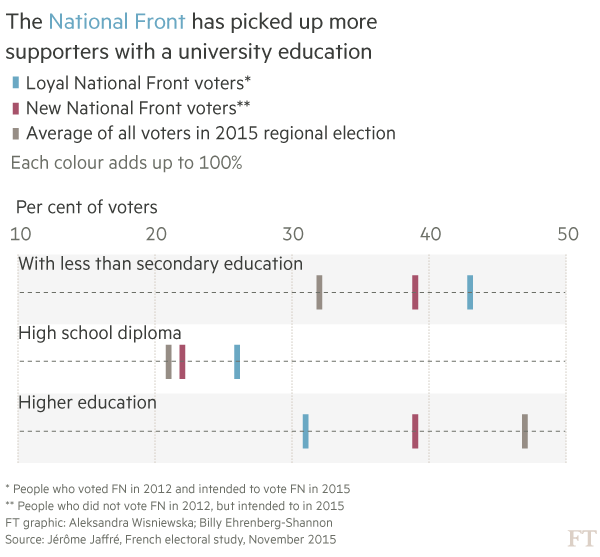

In the 2017 race, Mr Foucault says he expects Ms Le Pen to attract greater numbers of better-educated young voters than in 2012 or 2015. “Her electoral base is expanding,” he adds. “In the 2012 presidential elections, people who voted for Marine Le Pen usually did not have a baccalauréat [secondary school diploma]. This year, we expect that [more] people who have passed this exam will also vote for her.”

Mr Foucault attributes these gains partly to Ms Le Pen’s efforts to temper her image. “She seems to be less polarised, she has been listening to people and has made some progress,” he says. “It is different from, for example, her father who did not want to moderate his views and did not manage to attract any young voters.”

For Mr Foucault, however, the most significant novelty in this weekend’s vote is that highly educated people are less likely to participate in the elections at all, turned off by all of the candidates.

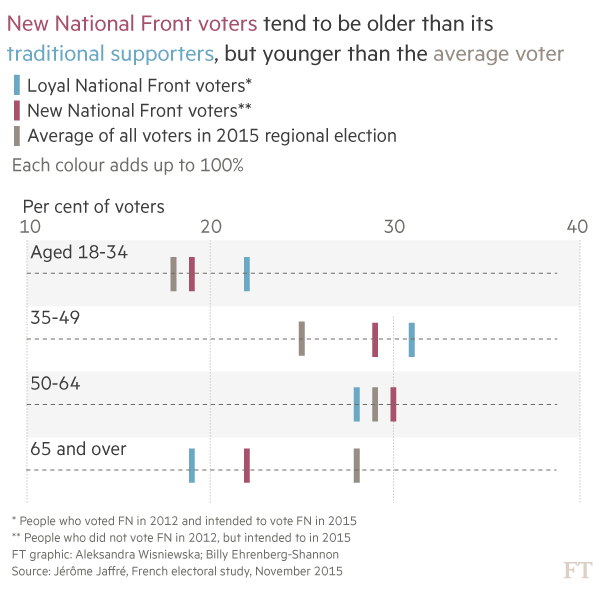

New National Front voters are older . . .

Increasingly, the FN appeals not only to educated voters but also to older age groups. These traditionally strong centre-right supporters are slowly turning towards Ms Le Pen, according to another piece of research from Sciences Po, which compared the electorates in the 2012 presidential and the 2015 regional elections.

It is axiomatic that as a society ages, older voters make up a bigger share of the electorate, making them ever more relevant to politics. They are also the age group feeling most abandoned by political elites.

The proportion of respondents over 65 who think politicians care about them “a lot” or “enough” stands at 10 per cent, lower than for 25-34 year olds (13 per cent) and voters aged 18 to 25 (16 per cent), according to a paper by Luc Rouban, director of research at CNRS. Senior voters are therefore starting to “defect” to the National Front — especially if they are also poor.

. . . and very radical in their outlook

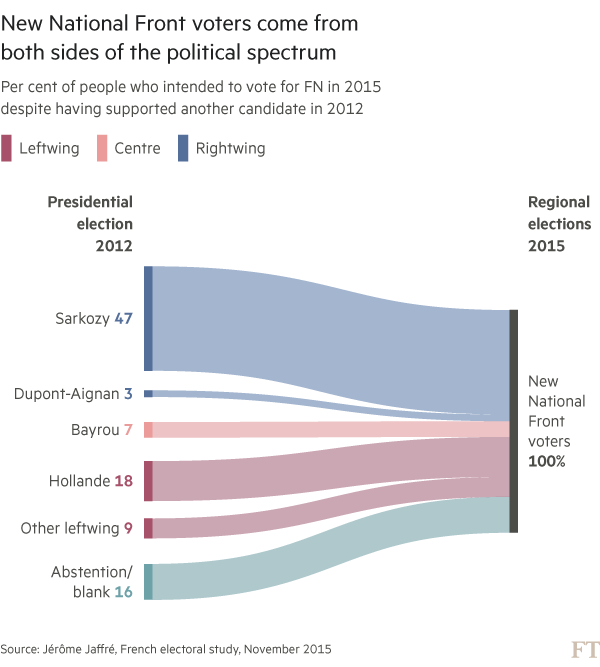

The paper has also shown that the FN has picked up support from both sides of the political spectrum, as well as among those who rarely or never vote. The interest of these previous non-voters or reluctant voters in the far-right party indicates the movement’s populist appeal — but it also means that extra care should be taken when interpreting opinion polls, since their voting patterns are, almost by definition, unknown.

Data from the French electoral study collected in November 2015, just before regional elections, show that almost half of those intending to vote FN had supported centre-right candidate Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2012 presidential race. However, almost one-fifth of new FN supporters said they had voted for François Hollande, the Socialist winner. Interestingly, as seen in the chart below, the attitudes of these former Hollande supporters on issues such as immigration, Islam or the death penalty is closer to those of traditional FN loyalists than those of former Sarkozy voters.

The changing nature of the FN electorate means far-right support in France is no longer confined to its traditional, limited support base. It is not solely driven by concern over immigration, nor is it just a protest vote, or the choice of blue-collar workers and hot-headed youth. It is the vote of the pessimists: those who feel unhappy, undercut and left behind.

. . .

*Electoral study by Cevipof, conducted in July 2016 among 17,000 respondents.

The following research informed the above article:

“Mal-être et Votes” by Yann Algan (Sciences Po), Elizabeth Beasley (Cepremap), Martial Foucault (Sciences Po), Paul Vertier (Sciences Po), Claudia Senik (PSE, (Cepremap)

“Les nouveaux électeurs du Front National”, by Jérôme Jaffré, director of Cecop

“Les trois France”, by Bruno Cautrès, professor at Sciences Po university

“La dynamique du Front National”, by Pascal Perrineau, professor at Sciences Po university

“Les seniors au centre de l’élection présidentielle de 2017 (étude n°1)”, by Luc Rouban, professor at Sciences Po Cevipof

Comments