The French town that shows how Marine Le Pen could win

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Quiet! Watch out! Enemy ears are listening,” warns a first world war propaganda poster on the door of Will Perez’s second-hand bookshop, near Béziers’ town hall.

Inside, in semi-darkness and surrounded by Nazi and colonial memorabilia, 65-year-old Mr Perez says he enjoys “provoking bohemian-bourgeois” tourists, coming for a taste of the French far-right town. Liberal hipsters from large cities do not realise that “France is being colonised”, he says. “I am no racist but I see these [Muslim] guys around, they stay among themselves, they don’t want to integrate. Islam is a religion of power. We must enter into resistance.”

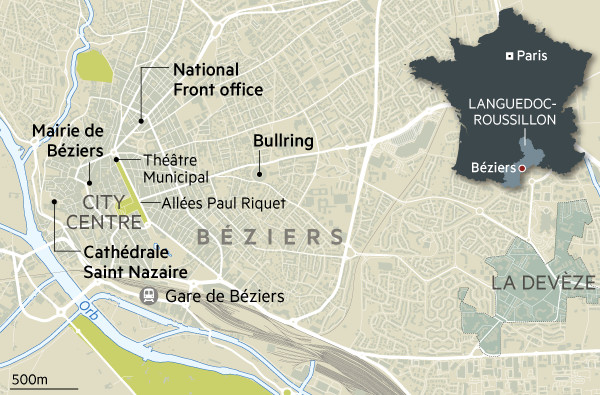

Under Béziers’s sleepy veneer — with its large tree-lined square and fortified cathedral overlooking vineyards — disquiet is brewing. The town of 75,000, squeezed along the Mediterranean coast between the larger cities of Toulouse and Montpellier, was historically a vibrant economic centre until its wine industry fell away in the 1970s.

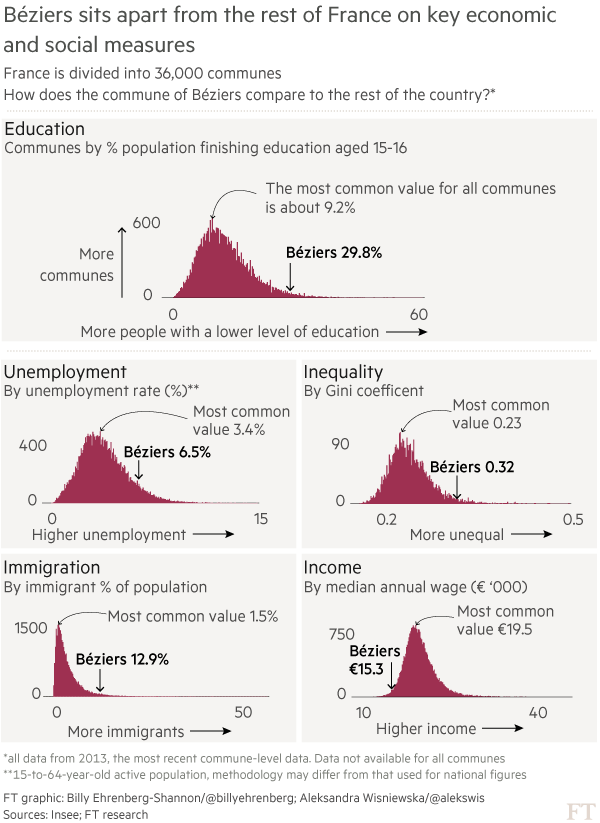

Today, one in five working age adults is unemployed, double the national average. The town grapples with some of France’s widest income inequalities. Its poorest residents suffered the second-biggest drop in earnings during the financial crisis, according to Observatoire des inégalités, a think-tank.

Béziers is a symbol of “peripheral France”, a term coined by French geographer Christophe Guilluy to describe struggling industrial bastions, suburbs and rural areas that feel abandoned by the central government and Paris establishment. In these disillusioned territories, a rightwing counter-revolution is under way, rooted in angst over French identity. In Béziers, as nationwide, the fear of a vanishing French way of life has translated into mounting anti-Islam sentiment and growing support for the political party that has seized on it: the far-right National Front (FN). Now, its leader Marine Le Pen is predicted to qualify for the second round of presidential elections on May 7 — the most certain feature in a campaign convulsed by scandals and the collapse of traditional mainstream parties. In an echo of the rising populist tide in Europe, a Le Pen victory cannot be ruled out.

The far-right strategy

Robert Ménard, the mayor behind Béziers’s far-right shift, is sipping mint tea in Najim’s café in La Devèze, a poor neighbourhood on the eastern rim of town. He gestures towards the male-only Maghrebi customers sitting in the morning sun to underline a looming clash of civilisations.

“Look around, 30 years ago, it wasn’t like that,” the 63-year-old politician says of the estate. He lived in this part of Béziers as a teenager: his Alsatian family settled in Algeria then returned to France when he was nine. “The population is changing, it’s a fact, and it’s a fact I dislike. This is France in 20 years,” he says, adding: “Minorities are never a problem as long as they stay minorities.”

Receiving the official backing of the FN — with which he shares many of the ideas but of which he is not a member — Mr Ménard was elected mayor in 2014 with 47 per cent of the vote, coming ahead of the centre-right Republican and Socialist candidates. He believes in the “grand remplacement”, a theory prospering in far-right circles that claims the French white middle class is being replaced by north African populations. (French Muslims accounted for about 5m, or less than 10 per cent of the total population, according to 2010 estimates by the Pew Research Center.) With this idea in mind and a law-and-order agenda, Mr Ménard has turned Béziers into a laboratory for local experiments in far-right strategies. But he is also nurturing a grander ambition: proving to Ms Le Pen that bringing the mainstream right and far-right together, as he did in his town, is the only path to the presidency.

For two decades, Béziers’s economic decline was presided over by centre-right politician Raymond Couderc. Mr Ménard, a journalist who appeared regularly on television, ran an energetic campaign as an independent with a plan to revitalise the historic centre and tackle petty crime. He managed to lure members of the previous mayor’s team. Many chose the charismatic Mr Ménard over Mr Couderc’s designated heir and official Republican candidate. This allowed Mr Ménard to attract not just FN supporters but also a more moderate rightwing electorate.

“I think the method I’m using here can be applied on a national level — getting a team that mixes the FN and the traditional right,” he says. “I am just a mayor. For the sake of Béziers, I want things to change on a national level too.”

As mayor, Mr Ménard has veered more to the far-right — though he rejects the term and says he is just the “true” right — mixing tough law-and-order measures with shouty slogans and aggressive public relations. He accepts that he is a “populist” (“I respect the people, I try to describe things as they are with day-to-day words”) waging war on a liberal, leftwing “intelligentsia who hate France” and who are allegedly to blame for the country’s woes. A practising Catholic, he has sought to return Christian traditions to the fore in France.

He armed the local police, plastering posters of handguns around the town with the warning: “Béziers has a new friend.” Local courts stopped him setting up a civilian militia, but he succeeded in banning the drying of laundry in public view in the historic centre — a habit of the town’s poorer Maghrebi residents. He raised eyebrows when he sought to impose a curfew for minors and caused outrage over a municipal weekly newsletter showing Middle Eastern migrants boarding a train with the headline: “They are coming!” He is facing litigation for stating on TV that two-thirds of primary school students in Béziers were Muslims — in France, the collecting of religious and ethnic statistics is prohibited.

Béziers residents largely applaud Mr Ménard, and welcome the attention. “I like that he shakes things up,” says Sabine Gély, an FN sympathiser who lives in a village outside the town. “The town’s centre was dying, there were vagrants and stray dogs. At least people are talking [about this town]. Before him, no one talked about Béziers.” Isabelle des Garets, a 55-year-old winemaker, shares the mayor’s anti-immigration stance. Running the 23-hectare vineyard that has been in the family’s ownership since the French Revolution, she says bitterly that her father, a retired fruit and vegetable grower “who worked hard all his life, lives off a €1,200 monthly pension, while immigrants can access healthcare”. A supporter of Ms Le Pen, she blames the EU for the burdensome norms and regulations: “Spain is flooding the market with cheap wine and prices have gone down. I doubt they apply all the norms there.”

Even within his administration not everyone is comfortable with Mr Ménard’s style. Valérie Gonthier, a councillor who had enthusiastically joined his campaign, quit in November because she disagreed with the mayor’s “ideological drift”. Some critics say most of Mr Ménard’s measures did not warrant all the attention they received from national media. About 40 per cent of local police in France already carry guns. His policies on curfews for minors have also been implemented by other towns to tackle petty crime (human rights activists who tried to stop Mr Ménard’s policy in court lost their appeal last month). Aziz El-Mahi, a 37-year-old lawyer who was born in La Devèze and regularly visits his parents there, says the restriction has hardly been enforced anyway. “I actually wish it were,” he adds. Mr El-Mahi is a leftwing sympathiser who is no fan of Mr Ménard.

“Ménard is doing the job,” says Arnaud Gauthier, a journalist at local newspaper Midi Libre who has frequently clashed with the mayor. “But he is also leading a cultural battle. The more popular he is, the more he’s pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable to say or do, as with his comments on Muslim children. He’s seeking to break down mental barriers.”

Residents of La Devèze

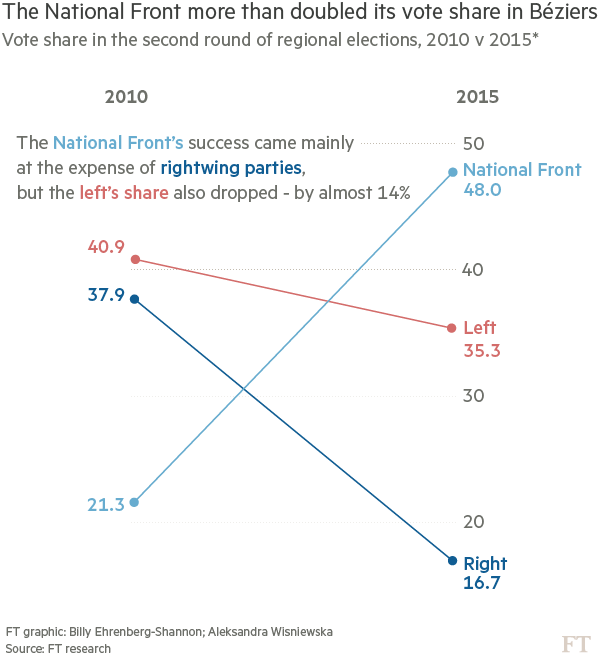

Mr Ménard’s victory in 2014 coincided with a surge in local support for the FN. In presidential elections in 2012, one in four Béziers voters had backed it. Two years later, one-third did so in EU parliamentary polls. In local elections in 2015, the far-right party attracted 48 per cent of the vote.

In contrast with the former Socialist industrial strongholds of the north, where the FN’s advances are more recent, the far-right party has had a solid base in southern France, especially among a large “pied-noir” population — the 1m French settlers in Algeria who were forced to move out after it won independence in 1962. Many were drawn to FN founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, who fought in the Algerian war and shared their resentment towards president Charles de Gaulle for negotiating the independence of what had been a French colony for 132 years. Pieds-noirs brought with them a strong anti-Arab sentiment, says Françoise Arnaud-Rossignol, a Socialist opposition city councillor in Béziers. She says she was shocked, when she moved from central France two decades ago, to see that “people were openly racist”.

Mr Ménard’s pied-noir family left his native city of Oran after nearly a century in Algeria. He remembers stepping over a body on the way home from school during the war, the guns hidden in the trunk of his father’s car, his older brothers eager to fight. In Béziers, life was filled with humiliations. At school, the young Robert Ménard was called “dirty Arab”. The family would make ends meet selling his mother’s cakes in the estate. They would talk about Algeria all day long.

Like many students in post-May 1968 France, Mr Ménard became a Trotskyist. As founder of Reporters Without Borders, a press freedom activist group, he climbed up Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris at night to unfurl a banner denouncing the authoritarian regime of Beijing, which was hosting the 2008 Olympic Games.

“I have changed. Thirty years ago, identity was not an issue, the mere fact that we talk about it shows there’s a problem,” he says.

When the first residents moved into La Devèze in the 1960s — pieds-noirs and Moroccan workers essentially — few spoke Arabic in public. Muslim women would not wear hijabs in the streets, says Claudie Escudie, a longtime resident. Today, the 9,000 inhabitants are mostly families of Moroccan immigrants who came to work in the region’s vineyards and farms circling the town. Some of the buildings are so rundown that they are going to be demolished. Veiled women rush by, while groups of youths wearing hoodies roam around, looking idle. A mustachioed retired truck driver from Meknes in Morocco, who has lived in the area for three decades and does not want to disclose his name, complains about insecurity. “It’s like Beirut here,” he says. That is why he voted for Mr Ménard, he adds. “If they deport you, you won’t be as happy,” snorts Ms Escudie, a leftwing sympathiser.

Like other towns in southern France, Béziers is not immune to the Islamist threat, says Mr El-Mahi. In 2001, a week before the 9/11 attacks on the US, Safir Bghioua, a 25-year-old radicalised Devèze resident, fired a rocket on the local police station and killed a city official with a Kalashnikov gun. In 2012, soon after Mohammed Merah killed soldiers and Jewish children in Toulouse, Mr El-Mahi saw youngsters in the neighbourhood celebrating the terror assaults. “They looked like youth on the fringes, completely lost,” he says. When he was a child, children from different backgrounds would play football against one another every Sunday. “Not any more. The wealthy residents send their children to private schools, Arabs stay among Arabs,” he laments.

Mr Ménard’s identity politics has brought Catholicism back to the fore. A statue of the camel of the legendary Saint Aphrodise, an Egyptian Catholic preacher thought to have been eventually executed by local authorities in the third century, welcomes visitors to city hall. This revival of old traditions has pleased a conservative electorate, says Robert Margé, a local breeder of fighting bulls. An example has been to reinstate mass before corridas in the town’s bull ring, as was customary in the old days. “I am a Catholic, we share the same values,” Mr Margé says.

Mr Ménard is more explicit: secular France should reaffirm its Christian roots over Islam to address “its moral crisis”, he says, adding: “Religions should not be treated on an equal footing.” Radical Islam, he claims, is spreading out of the banlieues. The mayor’s outright hostility saddens Mr El-Mahi but he says most Muslims in Béziers do not pay much attention to Mr Ménard’s provocations.

Template for victory

Mr Ménard wants the FN, which has thrived on these frustrations, to use Béziers as its template for presidential success. A condition for Ms Le Pen’s victory after the first round of voting on April 23 depends on her ability to unify other rightwing parties, he says. “Even though her ideas are increasingly mainstream, her party is still perceived as radioactive. She can only reach power by reaching out to the French right.”

Since succeeding her father in 2011, Ms Le Pen has sought to normalise her party — which has involved expelling her father after he made anti-Semitic comments. The final phase of this detoxification strategy is fast approaching, according to Jérôme Jaffré, a professor at Sciences Po Cevipof: if she qualifies for the presidential runoff against centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron, the far-right politician will signal she wants to work with the centre-right Republicans party, whose candidate François Fillon has been impeded by an embezzlement scandal.

“The question of whether or not to unite the French right is no longer a theoretical one for the National Front,” Prof Jaffré says. As in Béziers, where Mr Ménard managed to lure Republican councillors, such a scenario could split the Republicans between senior figures still viewing the FN as toxic and others eager to govern.

Meanwhile, electorates are coalescing. About 30 per cent of centre-right party voters, in disarray because their nominee Mr Fillon may not qualify for the runoff, say they would back Ms Le Pen in a second round against Mr Macron, while more than a third would abstain.

Far-right personalities from southern France, such as Mr Ménard but also Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, Ms Le Pen’s niece and an MP in Vaucluse, would help establish a bridge between the two parties. Practising Catholics, more conservative on social issues and holding free-market views, would also help lure Republican voters who do not agree with Ms Le Pen’s statist views on the economy and her plan to exit the euro.

The possibility of Frexit is what holds back many Republican voters from supporting Ms Le Pen, Mr Ménard believes. “It’s a stressful stance. I have spent hours telling her.” Her approach to the euro is simplistic, he says. “The EU is not responsible for all of France’s woes.” Mr Ménard knows Ms Le Pen well and speaks to her by phone every week. (She even offered a present — a pet cat — to his daughter, Clara.)

But on issues of immigration and identity, far right and mainstream right have already started to converge. It helped that in 2007 former centre-right leader Nicolas Sarkozy ran a successful campaign on those themes, marking the end of the left’s domination on values and social issues. “What’s the difference between a Republican voter and an FN voter now? Very little. In the south of France, nothing,” says Mr Ménard. “On the right, we won the battle of ideas.”

Comments