G7’s relevance cemented by G20’s dysfunction

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

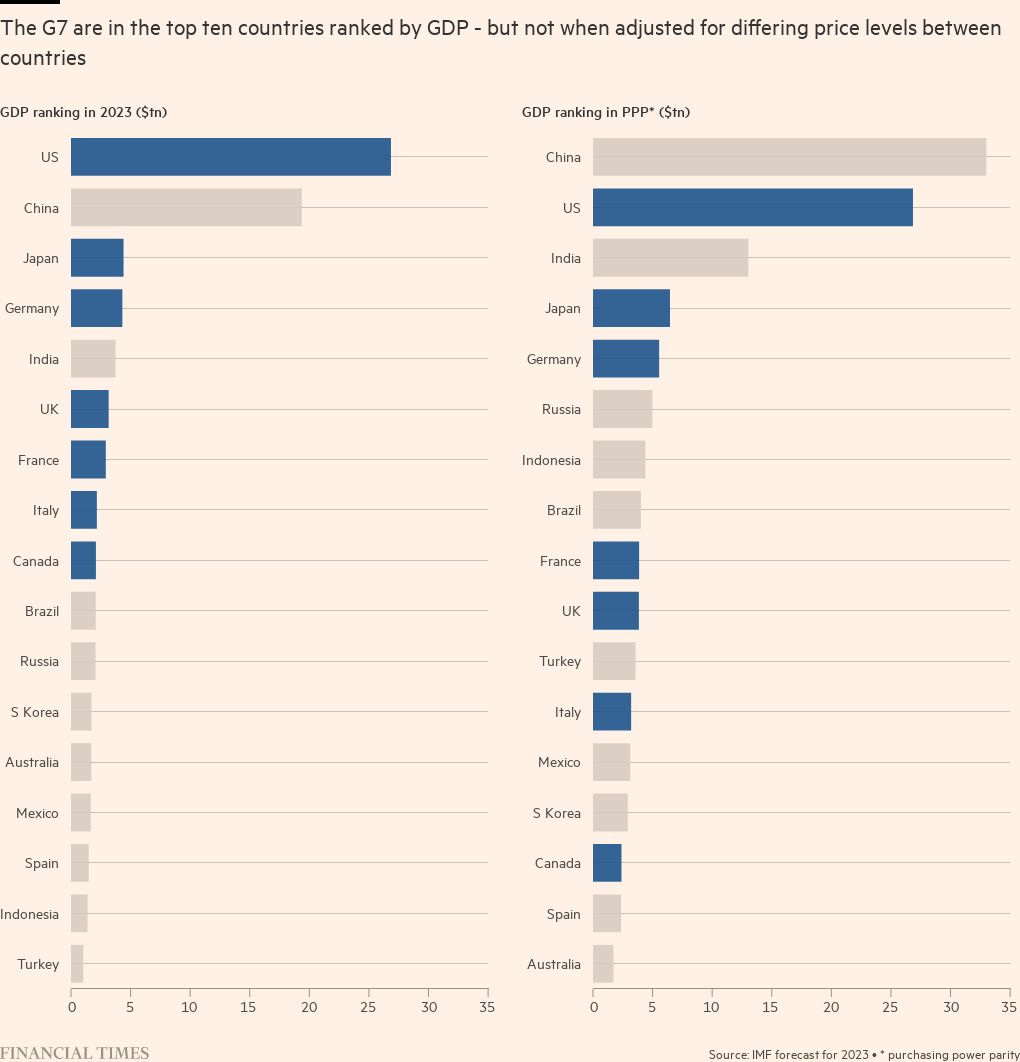

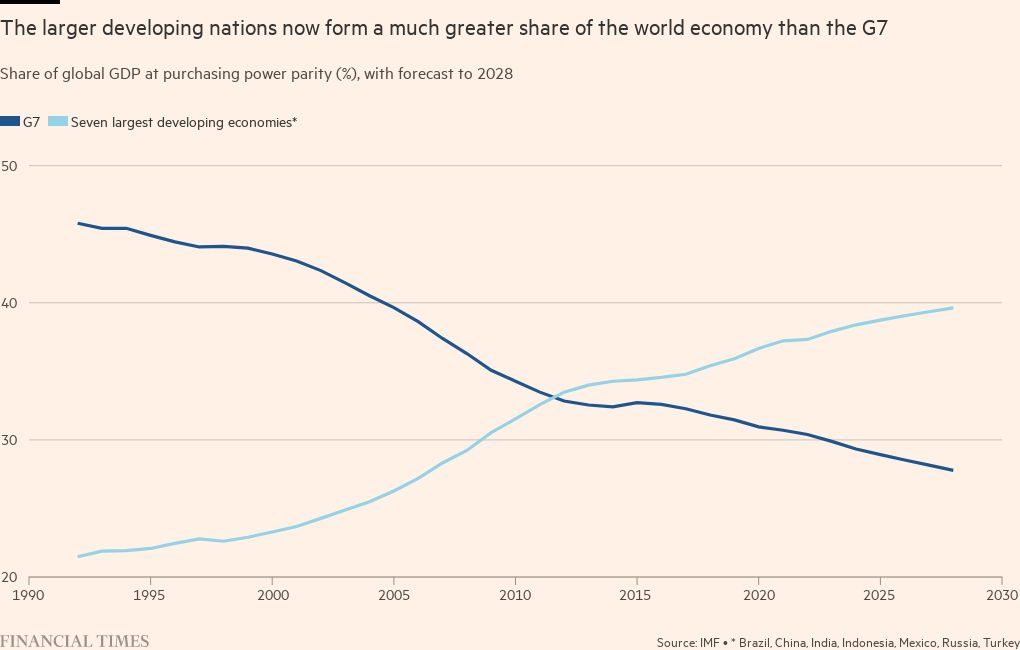

Towards the end of the acute phase of the global financial crisis in 2009, the Group of Seven appeared dead as an economic and political bloc. Representing only 35 per cent of the global economy, the then IMF head joked it was the “late G7”.

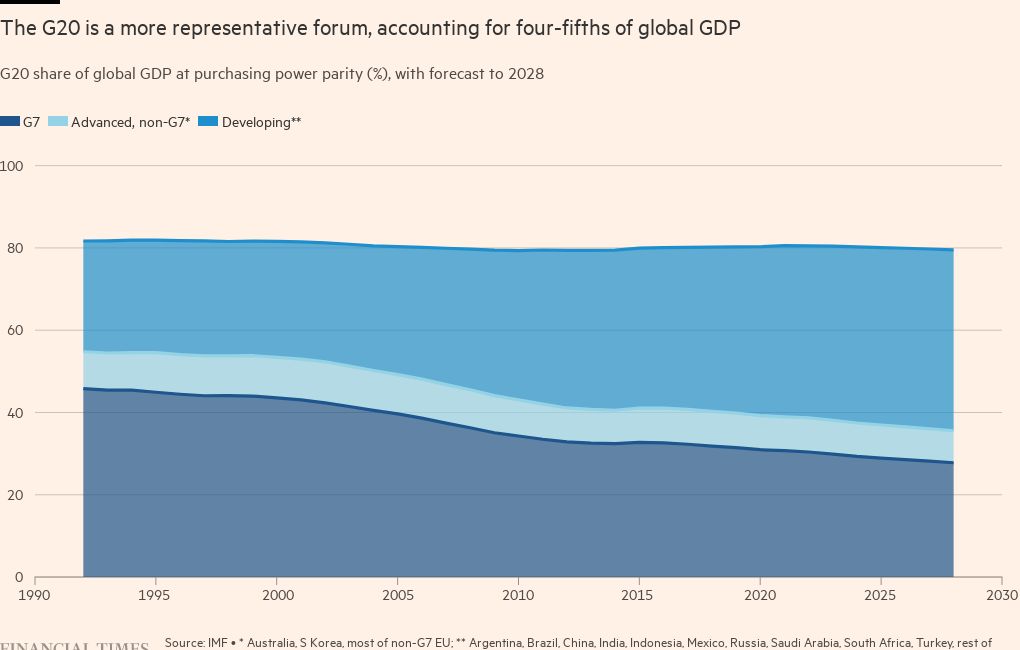

The plan was for France to perform the coup de grâce when it chaired the G7 and G20 in 2011. From that point on, the G20 would be the “premier forum for international economic co-operation” and decisions of global importance would no longer be taken by a small and unrepresentative club of just seven industrial countries.

The plan never materialised. Through the 2010s, G7 finance ministers of the US, Japan, Germany, France, UK, Italy and Canada met regularly with little consequence. National leaders met at a G8 level until 2014, when Russia was expelled for its annexation of Crimea, part of Ukraine’s sovereign territory. When Donald Trump was US president, the summits were occasionally spectacular failures.

In 2018, he left early, refused to sign up to a communique praising the “rules-based” system of global trade and called the host, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, “dishonest and weak”.

But the 2020s have been different. President Joe Biden’s administration has taken a shine to the G7 — not as the forum to thrash out global solutions, given it now represents only 30 per cent of global GDP — but as a body of like-minded advanced economies that are able to agree a united front. And this reappraisal has come at a time when the G20’s relevance in economic affairs has dwindled, with the body, including China, Russia and the US, unable to agree on much of substance.

Professor Eswar Prasad at Cornell University says: “In a rapidly fragmenting geopolitical order, the G7 represents a largely unified but now far from dominant block of countries with similar economic and political values”.

“Ironically, the dysfunctionality of the G20 and the open rancour among its members have led to the G7 regaining some of its relevance.”

The first indication of the renewed relevance of the G7 came early in the Biden presidency when his Treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, decided to cede some ground in some parts of international tax negotiations in order to achieve a US prize of a global minimum corporate tax rate.

She came to London to a G7 finance ministers’ meeting in June 2021 with a proposal to stop a race to the bottom of global corporate tax rates alongside a radical move to allow all countries to collect some tax from foreign multinationals doing business in their countries. Securing what all sides said was a “historic agreement”, the G7’s actions proved to be the catalyst for a later global agreement among 136 countries.

In 2022, the G7 cemented its newfound relevance for western nations by acting as the forum to calibrate and set sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine.

By September, the bloc had agreed a price cap on Russian oil — aiming to allow the oil to flow and to keep global prices down, while depriving Moscow of significant revenues from fuel.

This was imposed in December last year at a price of $60 a barrel with subsequent caps on petrol, diesel and other fuel oils effective from February this year. In an assessment of the sanctions, Elina Ribakova, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, says that the G7’s actions, seeking to limit flows of money to Russia from oil exports, were “a smart thing to do” although there were huge incentives for Russia and shipping companies to seek to circumvent the price cap.

Noting the lack of officials or procedures to enforce the cap, Ribakova adds, “it’s novel, but the G7 is trying to implement economic statecraft without an institutional set-up,” suggesting the cap was likely to get increasingly leaky. Those concerns, however, did not invalidate the overall effect of the G7 and EU’s sanctions, she says. Other measures and sanctions would intensify the squeeze on Moscow’s finances: “Russia’s economic challenges will only worsen as the war continues with no end in sight”.

John Kirton, director of the G7 research group at Toronto university, says these actions and others showed that the G7 was able to produce robust conclusions to summits that were useful for the world at a time when “the G20 is missing in action”.

“This year, what we’ve seen so far, empirically, is that the G7 is on the road back to life on everything — on macroeconomics, security, Russia’s war in Ukraine and energy,” Kirton says, adding that his group’s research showed that member states generally implemented and complied with agreements struck at G7 summits.

The Hiroshima summit will take the G7 into a further new area for 2023, though. In finance ministers’ meetings so far this year, the ministers have focused on building economic resilience and security, trying to define a world of “de-risking” from China — reducing dependencies on critical elements of supply chains, rather than “decoupling” and casting the country into the economic wilderness.

The finance ministers concluded in April that, “in this endeavour, we will stand firm to protect our shared values, while preserving economic efficiency by upholding the free, fair and rules-based multilateral system and international co-operation”. That will be a considerable challenge in 2023.

Comments