G7 prioritises ‘de-risking’ China links over ‘decoupling’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the months leading up to the G7 summit in Hiroshima, the US, EU and Japan cautiously united behind a policy towards China that rules out a full decoupling of trade between them — as the world’s most advanced nations — and Asia’s largest economy.

But how the G7 will strike the right balance between national security and economic interests remains a challenge that is likely to weigh heavily during the summit meeting. The gathering will also be joined by leaders of developing countries including India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brazil and the Indian Ocean island-nation of the Comoros.

“What Japan intends to do, rather than decoupling from China, is to strategically identify areas where collaboration is possible and areas where risks should be avoided,” said Yoshimasa Hayashi, Japan’s foreign minister, in a written interview with the Financial Times. “The Japanese government will continue to encourage co-operation in the economic field in a manner that contributes to the national interest of Japan as a whole.”

This so-called de-risking strategy is an approach first put forward by European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen in March, when she called for “new defensive tools” for sectors such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence. Since then, UK and Japanese officials have started adopting that same phrase, while the US is emphasising that its China policy is focused on “de-risking”.

At the summit, in addition to tackling Beijing’s military ambitions and the risk of a conflict over Taiwan, prime minister Fumio Kishida will aim to project G7 unity in addressing economic security, generally. But a pillar of that initiative involves how the member countries can collectively deter other nations — notably China — from using economic pressure to try to force individual governments into political concessions.

“All of the G7 countries do not have a hardline approach on China but they can agree on where they need to protect themselves against China and the newest element [to that debate] is how they need to respond against economic coercion,” says Ryo Sahashi, associate professor of international politics at the University of Tokyo.

Sahashi says it is unlikely that the G7 members would agree on new economic security tools, such as export controls or an anti-coercion instrument, at the Hiroshima summit, but he adds that “maintaining the momentum” to work together on this issue would still be important.

The US, the EU and Japan agree on the importance of economic security and the need for the so-called “like-minded countries” to collaborate to protect critical technologies, intellectual property, and supply chains.

Also in this Special Report

However, the approach taken by each country has been different, influenced largely by the extent of its reliance on the Chinese economy.

The Biden administration has pursued the most aggressive path to decoupling China from the US in cutting-edge technologies, while Europe and Japan have taken a more selective approach given the deep ties and intricate supply chains they have established in China.

Tokyo also feels more vulnerable to Beijing’s retaliation if the G7 pushes too far, having experienced a cut-off of rare earth mineral supplies in 2010 and the arrest of 17 of its nationals in China since the country passed a counter-espionage law in 2014. China has already criticised the G7’s focus on economic coercion, saying that it was the victim of economic bullying by the US.

“China knows very well that Europe tends to see the economy before national security in their relations with China, so China is likely to attempt to split Europe using its economic strength,” suggests Nobukatsu Kanehara, former assistant chief cabinet secretary during the administration of late prime minister Shinzo Abe.

“In Japan’s case, Taiwan is right in front of their eyes so Japan feels decoupling of cutting-edge semiconductor technology is inevitable, but it still needs to find a balance since full decoupling is impossible,” he explains.

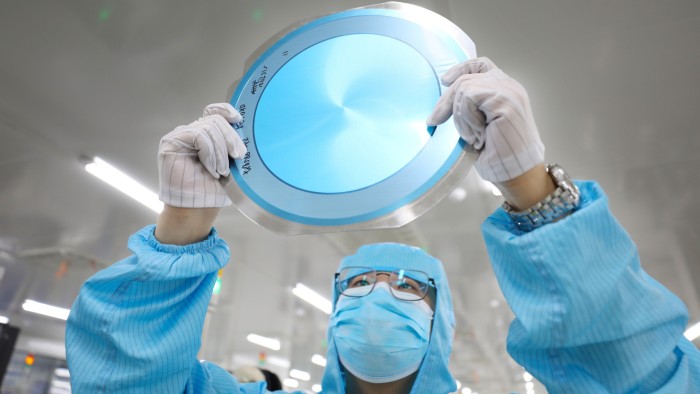

The US last year introduced sweeping export controls that would severely complicate efforts by Chinese companies to develop cutting-edge technologies with military applications. Washington is now seeking the support of its allies as it finalises a new outbound investment-screening mechanism aimed at China.

Brussels is also examining the creation of its own mechanism for scrutinising overseas investment by EU companies in a small range of sensitive technologies that could enhance rivals’ military capabilities. But officials are unlikely to agree to “a shared mechanism” with the US.

Meanwhile, Japan has unveiled curbs on the export of 23 kinds of technology as part of a deal reached with the US and the Netherlands in March. In both Europe and Japan, though, the measures are not targeted against a single country.

Rahm Emanuel, the US ambassador to Tokyo, has argued that a response to Beijing’s economic coercion needs to “be collective and must be led by the United States”, but Tokyo still prefers to use the World Trade Organization as a mechanism to resolve disputes.

“The difficulty about economic security is that countries are both collaborators and rivals,” observes Kazuto Suzuki, professor at the University of Tokyo. “If US companies suffer, it’s an opportunity for Germany, France and Japan. That is why the thinking of the US, EU and Japan will be different and it will be difficult to reach a consensus on how aggressively they will use export controls against China.”

Comments