Young dealers with Old Masters find support at Tefaf

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Willoughby Gerrish’s first experience of Tefaf in Maastricht came when he was just 20, a student working for The Fine Art Society. This year, after nine years at the gallery, and five with another longtime fair participant, he returns to the world’s pre-eminent art and antiques fair as an exhibitor in his own right. He is one of 10 early- or mid-career dealers taking part in the expanded Showcase section, which supports and promotes the next generation of exhibitors by offering small, low-cost stands to those who have been in business for between three and 10 years.

“For a young dealer like me to be in the same room as 50 major dealers in our area is hugely helpful,” says Gerrish. “It gives us access to clients who we would never meet otherwise.” Showcase’s smaller stands are subsidised at €8,500; the average cost in the main fair is €51,000.

It is a dream of an opportunity for those attempting to make their name — and arguably a crucial investment for an established art fair, particularly one offering older art and antiques, which have far fewer new dealers than contemporary art.

Showcase has worked well for Tefaf. Of the 78 dealers invited since 2008, dozens have gone on to become regular participants. More than 30 of them are exhibiting this year or have done so recently. Two serve on the fair’s organising executive committee, including its president, Hidde van Seggelen. (His predecessor Ben Janssens conceived the initiative.) Perhaps the real measure of its success, however, is that the concept has been adopted in one form or another at many of the other big international fairs where stand costs are high and waiting lists long.

“The vast majority of young people setting up galleries or businesses are selling contemporary art,” says Will Korner, Tefaf’s head of fairs. “This expansion of Showcase is about making space for young people whose interests mirror the full scope of Maastricht.” The move upstairs in Tefaf’s hall, where there is space for both more dealers (previously there were six) and bigger stands — now 12 square metres — is also timely. “We felt that we should make more of this platform because things have been very challenging for a lot of galleries,” Korner says. “Fairs are shutting down, dealers are giving up their galleries, and people have had to change the way they do business.”

Gerrish, who set up his business in 2019, has an unusual model, dependent on art fairs. He runs a programme of six exhibitions a year of predominantly modern and contemporary sculpture, but also fine art, in indoor and outdoor spaces at Thirsk Hall in Yorkshire in the north of England, and deals privately out of an office in London’s St James’s. “If we do an exhibition in London, we tend to show it at an art fair,” he says. One of those fairs was the now defunct Masterpiece. “Given what I am selling, it makes absolute sense for me to do a European fair . . . Maastricht is the only European fair where you can guarantee seeing a ton of US museum curators.”

Another bonus of the Tefaf halo: “Clients are suddenly prepared to give you bigger, better works on consignment.” He brings pieces by Henry Moore and Lynn Chadwick, a Kenneth Nolan Diamond painting and a Braque from 1925, plus works by Rodin, Lipchitz, Laurens and a Gauguin bronze.

“This is third time lucky for me,” says Carlo Milano of Callisto Fine Arts about his Showcase application, “which I think says something about the selection criteria of the fair. You have to be ready.” Starting out as an academic, he moved from buying in the virtual world and selling at auction to acting as wholesaler supplying the trade before opening in St James’s in 2020. He has already shown at Frieze Masters, Fine Arts Paris, Brafa in Brussels and at the biennale in Florence.

He was surprised to find young collectors too. “My generation — I am 51 — has been completely swallowed by contemporary art, and I doubt it will ever be interested in historic art. On the other hand, I see thirtysomethings who, perhaps as a rebellion against the hegemony of contemporary art, are beginning to be interested in the art of the past. Their approach is entirely different.” At Tefaf, he offers a marble bust of Paulina, after the antique, and a monochrome by the Italian abstract painter Piero Ruggeri, “who needs to be rediscovered”.

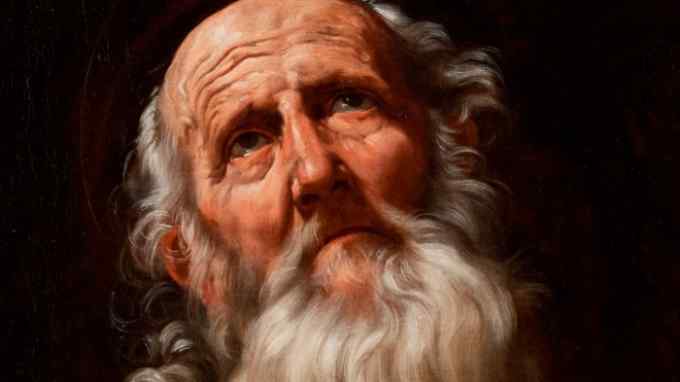

While Baroque art specialist Miriam Di Penta focuses on largely well known Old Master painters, others look to the rediscovery of artists, or types of works of art. Will Elliott, who like Di Penta previously worked for Sotheby’s, is focused on academic artists deserving re-evaluation. He brings the likes of Anton Grüss’s “Portrait of a Woman in a Red Turban” (1844) — a rare depiction of a black sitter painted in the Habsburg empire in this period.

New York-based Ambrose Naumann, 34, who worked with his father, Old Master dealer Otto Naumman, until the latter retired, found himself drawn to the period 1850-1950 and “lovely niche artists that no one knows outside their countries of origin”. He was buying women artists before they were “in”, and where once he sourced his stock mainly in France, Germany and England, now he is just as likely to buy in Poland or Romania. Not only is this financially viable for a young dealer without serious financial backing but he finds the cycle of constant discovery and research fun. He describes Liselotte Schramm-Heckmann’s “Delphinium” (1947) as a perfect example of a picture by a highly accomplished artist who, like many women, never really had a market. “It is all about finding quality, condition and value, and telling a story,” he says.

His words were echoed in many conversations with these exhibitors. For antiquarian book dealer Alexandre Pingel, 28, who used Instagram to reach a new audience during the pandemic, “younger customers prioritise visual appeal and align pieces with their personal values”. He brings a 1508 copy of the first printed compilation of Europeans’ voyages made in the eastern hemisphere, which includes the earliest large map of Africa.

“Someone hoping to exhibit long term has to consider whether they can make the financial commitment and also fulfil the extra demand,” says Emanuel von Baeyer, an exhibitor in the main fair who was in the first Showcase intake. “You also need people to help you, which is difficult if you are a one-man band. I had wonderful people around me, all in their late twenties, and all have made a career in art.” Showcase, it seems, is an exemplary nursery.

March 11-19, tefaf.com

Comments