Antwerp’s fine arts museum brings a female Old Master back to life

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Of all the things you would want to do to an Old Master painting, ironing it is probably fairly far down the list. But that was what happened during a restoration of Michaelina Wautier’s “Two Girls as Saints Agnes and Dorothea” (c1650), a humane, penetrating picture in the possession of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA). The canvas was left with small burn marks. Now, thanks to a grant of €25,000 from the Tefaf art fair’s Museum Restoration Fund, the scorched painting is going to be re-restored, fixing faded colours too.

Tefaf established the Museum Restoration Fund in 2012 to support galleries around the world which had works (from any era) in need of careful conservation. It awards €50,000 annually and this year’s other bursary goes to the Neue Galerie in New York for Egon Schiele’s “Town among Greenery (The Old City III)” from 1917.

“Wautier is an extraordinary female artist so she really belongs in this museum on the walls,” says Carmen Willems, KMSKA’s general director, as we look at the painting in its claret-coloured gallery. “She doesn’t belong in the storage rooms.” And as Willems points out, the collection — like most — is not rich in female Old Masters, which gives the restoration added impetus.

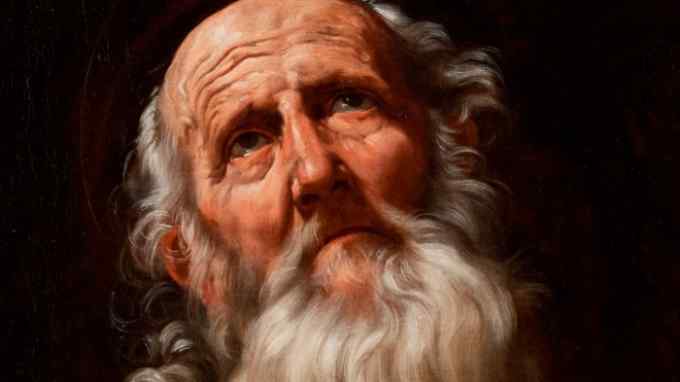

As with her “Education of the Virgin” (1656) in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, this picture has a sensitivity to the mood and physiognomy of the girls’ faces rare in Old Masters. Here they have a certain pique or wariness, as if tired of sitting for the painter for hours swathed in silks — hardly saintly, wholly human. Compared with some of the other painted children in the museum, who look more like haunted balloons, Wautier’s girls could turn around and address you.

The painting has had a more metaphorical restoration: although the Flemish artist was well-regarded during her lifetime (1604-89), after she died this picture was attributed to an anonymous painter, then to Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert. It was only in 2003 that an art historian definitively reascribed it to Wautier.

In KMSKA’s restoration studio, which the public can peer into through a glass wall, another Wautier is undergoing repair, ahead of an autumn exhibition. Conservator Paula Aleixandre is tending to “Portrait of a Young Man” (1655), a headstrong fellow with dark locks whose canvas is rather badly scratched. With this and “Two Girls”, Aleixandre stresses the importance of reversibility: don’t do anything to a painting which future restorers could not undo.

That is not an approach the museum’s board and executives took when it came to restoring KMSKA itself. After an 11-year closure, the 19th-century neoclassical museum reopened last September with 40 per cent more display space, having filled in internal courtyards to create lofty, glossy white cubes. Showing works after 1880, including rooms devoted to the macabre, cynical paintings of James Ensor, they rebalance the appeal of the museum, best known for its grand gallery of Rubens.

There are now, says Willems, “two worlds in one museum”. It might even be fairer to say there are two museums in one building: the architect behind the €100mn transformation did not want visitors to slip between old and new as it would confuse the navigation, so there is no quick way to get from Hans Memling’s 15th-century angelic orchestra to Rik Wouters’ fauvist “Etching Table”. But both halves become more potent this way, proving that some restorations are best done with fidelity — and others with flair.

This article has been updated to change the painter’s nationality

Comments