China ramps up coal power while pushing for renewables

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“China always honours its commitments.”

So began a speech in late 2020 by Xi Jinping, the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, just months after he stunned the UN General Assembly in New York with a promise to cut China’s net carbon dioxide emissions to nearly zero by 2060.

Barely three years later, however, and President Xi’s hallmark climate commitments — which also include a promise for China to hit peak carbon before 2030 — are once again making the news.

Many environmentalists believe a renewed coal frenzy threatens to undermine Xi’s ambitions. Other analysts, however, claim unprecedented investments and technological advances in renewable energy mean China is on track to hit Xi’s targets, possibly even ahead of time.

The stakes could hardly be higher. China is the world’s biggest polluter, responsible for about a third of the planet’s annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. So, as the World Bank has stated, global climate goals will be “impossible” to achieve unless the country transitions to a low-carbon economy.

Already, the Beijing office of Greenpeace is sounding the alarm. In the first three months of 2023, provincial governments in China approved more new coal-fired electricity generation than they did in all of 2021, the environmental campaign group said.

This new flurry of investment in the fossil fuel — which emits far more GHGs when used in power plants than natural gas does — comes against a backdrop of concerns over energy security and economic stability. Coal is still seen as the easiest and cheapest fix for local governments to ensure that the electricity supply is not interrupted.

Many provincial leaders are wary of power disruptions after months of shortages in 2021 and 2022 — when China’s north-east cut power to households, while extreme heat and a crippling drought in the south-west caused rolling blackouts at factories.

Now, the consensus view among experts in Beijing is that anxiety over energy security continues to outweigh the climate crisis, says Li Shuo, a Beijing-based senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace. That is despite the negative impact new coal will have on China’s emissions profile and its decarbonisation agenda.

“The rhetoric from the energy regulators [and] policymakers has not changed,” Li says. “There is still a very strong push for energy security, pivoting coal back to centre stage. It is, of course, not good news . . . it makes getting rid of them at a later stage much more difficult.”

There are also worries that new coal-fired plants will result in stranded assets, creating more problems for the Chinese economy in the future. However, Li points out that, in provincial leaders’ political calculus, a power blackout, even of just one or two hours, “is far more costly” than billions of dollars in stranded assets.

“In China, it is never just ‘Economics 101’, it is ‘the Political Economy 101’,” he explains.

China accounts for about half the world’s consumption of coal and the World Bank has said that the country’s energy transition will require an unparalleled “shift in resources, innovation, and new technologies to enhance energy efficiency and resource productivity”.

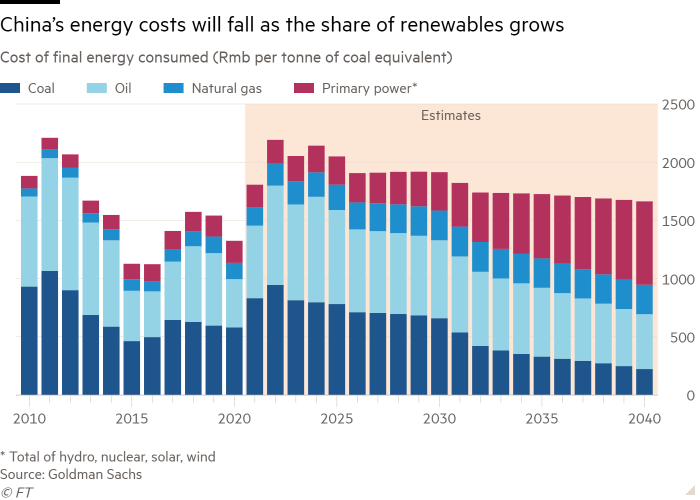

As a result, such a shift will be felt far beyond China. It could hit large chunks of the commodity trade with Russia, Australia and Indonesia, among others. At the same time, though, China’s ascendancy in clean technologies — such as solar, wind and batteries — will reduce costs for countries in the region. Climate activists are also watching to see whether Chinese companies make good on another Xi pledge: to stop funding new coal power stations overseas.

According to a new set of forecasts by investment bank Goldman Sachs, the country’s journey towards cleaner energy is well under way.

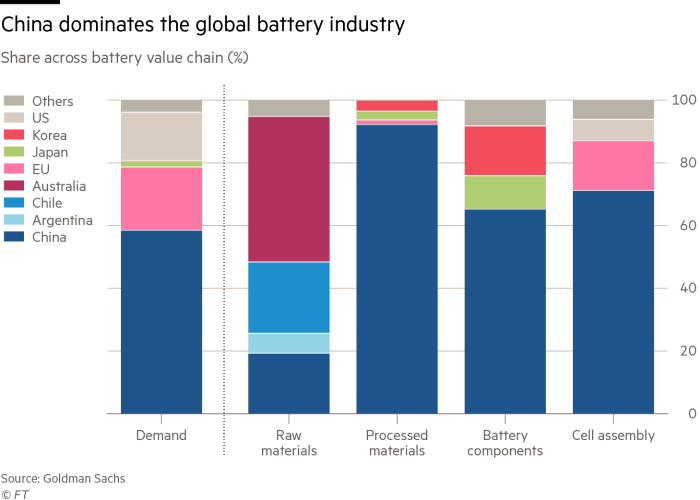

Nikhil Bhandari, co-head of research on Asia-Pacific natural resources and clean energy, points to China’s leading position across the value chains of solar, wind and batteries as evidence that the “building blocks” are in place.

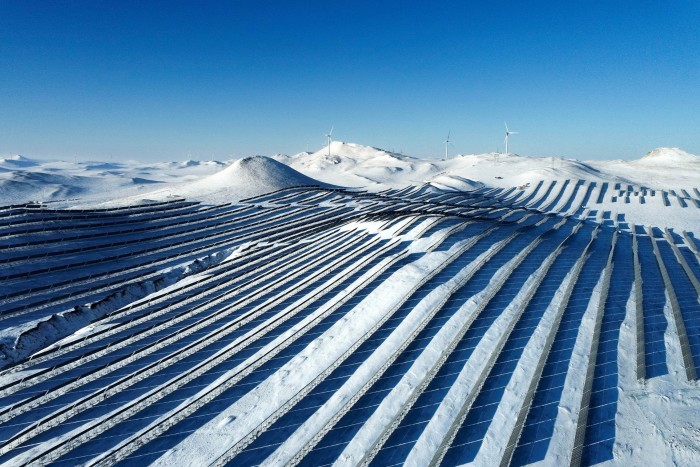

China boasts about 30 per cent of the world’s installed solar capacity, and controls about 90 per cent of the market for the key components that go into solar installations. Its wind turbine manufacturers have about 30 per cent of the global market, ahead of rivals in Denmark and Spain.

In batteries, which are increasingly important not just for electric vehicles but also in backing up intermittent renewable energy, China dominates most of the supply chain for midstream materials and cell assembly. Manufacturer CATL, alone, has cornered more than a third of the global EV battery market from its headquarters in Ningde, a former fishing village in south-east China.

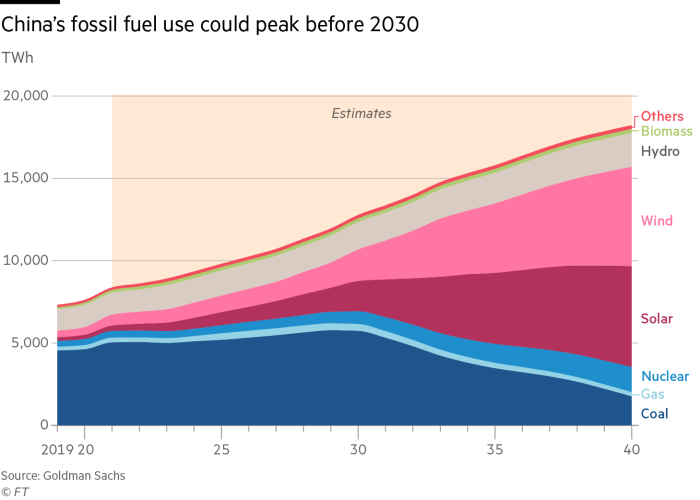

The improved economics of renewables and stored energy, driven by technological advances and significant reductions in solar and battery costs, underpin Goldman’s forecast that, by 2030, China’s combined solar and wind capacity will reach 3.3 terawatts. That is nearly triple the target of Xi’s energy planners in Beijing.

This new Goldman modelling implies that fossil fuel related carbon emissions could peak ahead of the 2030 timeline.

Also important — given Beijing’s increasingly adversarial relationship with the US and its western allies — is the fact China will be nearing energy self-sufficiency by 2060, as coal’s role fades. A “tipping point” of more than 50 per cent self-sufficiency is forecast for the early 2040s.

But a key focus for the government needs to be investment in energy storage and the electricity transmission network, to address concerns over blackouts, says Bhandari.

“The biggest hesitation in going all out in renewables is the reliability factor,” he says. “Over the coming decade, we believe China will invest more in the smart grid and the transmission system, and also increase the battery attachment rates for renewables.”

That in turn, he thinks, will accelerate the turn to renewables and “ultimately become a one-stop solution” for an affordable, reliable and self-sufficient energy system.

Yijing Wang — founder of Hangzhou-based 2060 Advisory, a firm that advises clean-tech entrepreneurs and investors — says that, in the past two to three years, the investment scene has undergone a “crazy” shift in focus towards decarbonisation industries.

She points to the wider context of slowing global growth, a weaker consumption outlook in China, and regulatory uncertainties for companies popular with investors. This has led to a reassessment of the outlook for Chinese consumer brands, technology, media, and telecoms companies, as well as online education.

By comparison, in the clean tech sector, investors can at least be certain about the direction from Beijing. “From 2020 there has been such a clear policy,” she says.

Ultimately, meeting China’s key decarbonisation targets will be “really tough” but “achievable”, Wang reckons. However, as China becomes the world’s biggest and lowest cost producer of clean tech products, she believes the west might need to ask itself a different question: “If we have very cheap low carbon technologies, and we export to the rest of the world, does the rest of the world think that is a good thing?”

Comments