Chipmakers race to curb emissions as demand surges

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A greener future is not necessarily a lower-tech future. On the contrary: policy experts at the International Energy Agency and World Economic Forum see smart, data-driven energy systems as crucial to hitting net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

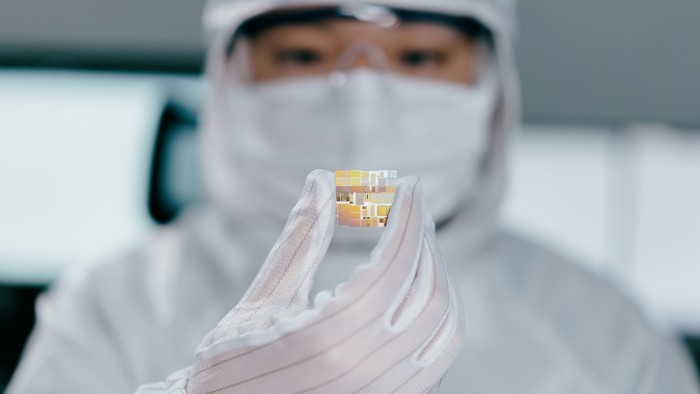

But the chips at the heart of all that clean tech — found in everything from wind turbines to electric vehicles and smart grids — come with a big carbon footprint.

According to Harvard research published in 2020, chip manufacturing, not energy consumption, accounts for most of the carbon output from electronic devices. Take water use: a chip fabrication plant can use tens of thousands of cubic metres a day, with each cubic metre creating over 10 kilogrammes of carbon emissions through transportation and purification.

Record growth in chip demand in recent years also means more energy is used by manufacturers. Emissions increase with the size of production plants, meaning the carbon footprint gets larger as companies rush to build out capacity.

The problem is most pronounced in Asia-Pacific, which dominates the world’s semiconductor industry, with regional revenues of $330bn in 2022, more than half the global total. South Korea and Taiwan are home to the most advanced chipmakers and, although both countries are aiming to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, their semiconductor giants currently have carbon footprints to match.

For example, in 2020, emissions from Taiwan’s TSMC — from its own operations (so-called Scope 1) and from the energy it purchased (Scope 2) — were about 10mn tonnes, not far off the levels for Taipei City. South Korea’s Samsung emitted 15.6mn tonnes in 2021.

Now, however, chipmakers are trying to shrink those footprints, helped in some cases by sister companies with green energy expertise.

Making greater use of renewable energy may seem an obvious way for these companies to move closer to net zero: in 2021, for example, renewables accounted for just 9 per cent of the electricity consumption at TSMC’s production plants.

But it remains a tough task in Asia. Nearly all of Taiwan’s energy, and about two-thirds of South Korea’s, comes from fossil fuels. And none of the big chipmaker’s climate commitments are in line with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, according to a report by campaign group Greenpeace.

Even so, companies including Samsung, TSMC and South Korea’s SK Hynix have announced aggressive measures to get all their energy from renewables by 2050. These efforts are likely to give a further boost to two growth technologies: green hydrogen and energy storage systems.

Hydrogen is already a crucial input for chipmaking plants. Access to cost-effective “green” hydrogen, produced without generating any CO₂, has long been a key goal for manufacturers. In Europe, the shift has started, with gases company Linde supplying chipmaker Infineon in Austria.

This potential for hydrogen as a fuel has spurred further interest. “Hydrogen will undoubtedly play a major role as a fuel in many regions of the world,” says Juergen Guldner, general project manager for hydrogen technology at carmaker BMW. “Hydrogen is one of the most efficient ways to store and transport renewable energy, making it a key player in future energy supplies.”

The trouble is that most hydrogen is currently derived from fossil fuels, with significant CO₂ emissions. That will have to change if it is to become a mainstream fuel, Guldner says. “The success of hydrogen will depend on competitive production of sufficient quantities of hydrogen from green power,” he stresses.

Another challenge is creating the infrastructure that can transport hydrogen as a fuel to end users. Samsung’s engineering arm, Samsung C&T, has set up alliances with local shipping and construction companies to build out a full hydrogen industry value chain, from overseas production of green hydrogen to domestic delivery. It also produces and distributes clean hydrogen derived from ammonia, which is considered easier to transport over long distances. Another Samsung unit specialises in green propulsion systems for ships, including hydrogen carriers.

But building infrastructure is a slow and costly process. A more immediate solution to the green energy shortfall has been to increase the use of energy storage systems. These can compensate for the intermittency of wind and solar power, maximising its efficiency by storing electricity during off-peak hours.

Here, the sister companies of South Korea’s chipmakers are in a strong position. Samsung SDI, for example, is one of the world’s largest makers of energy storage devices, accounting for about tenth of the global market, while SK Hynix affiliates account for another 6 per cent.

The market for energy storage systems is growing fast as governments revise their emissions targets — research firm Allied Market Research expects it nearly to double in size to more than $430bn by 2030. Unlike batteries for electric vehicles, these storage systems face few constraints on size and weight, so an increasing number of battery cells are being loaded into them and it is proving a lucrative business. In April, Samsung SDI reported record first-quarter results, with earnings topping $4bn.

Going all out for renewables is now a priority for Asia’s chipmakers as they seek to match new capacity to forecasts of booming demand — driven in particular by the recent spectacular rise of artificial intelligence — while also responding to growing pressure to curb emissions.

The green energy solutions that their subsidiaries can provide offer a rare example of companies’ financial interests aligning readily with those of their regulators.

Comments