Doubts linger over Biden’s industrial push

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

By the end of the second world war, the US made half of all manufactured goods globally — shipping gleaming home appliances and cars to an emerging middle class. The state of Pennsylvania alone produced more steel than the defeated nations of Germany and Japan combined.

But, over the past 50 years, manufacturing’s share of gross domestic product in the US has more than halved to 12 per cent. Cheap Chinese imports began flowing into the US in the early 2000s and, by the end of that decade, China had become the world’s dominant manufacturer, at the cost of almost 6mn American jobs. Today, US consumers buy fewer domestically produced goods than consumers in Germany or Japan.

Now, though, a boom in factory building has raised hopes of a “manufacturing renaissance” in the US.

More than 100 construction projects, worth in excess of $200bn, have been announced since the passage in August 2022 of two pieces of legislation, the Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, according to FT research. That is more than double the capital spending commitments in 2021 and more than 20 times those in 2019.

However, some question whether this boom is sustainable, given that it is driven, at least in part, by $369bn in clean energy tax credits and subsidies that are set to expire in 10 years.

“I certainly think the clean energy stuff is entirely driven by policy,” says Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former official in the George W Bush administration who is now president of the American Action Forum, an economic think-tank. “And if you turn the policy off, you’re going to stop a lot of that construction.”

But others insist the flurry of activity represents a historic shift. The building boom erases “a couple of decades of conventional wisdom about the future of manufacturing in the United States”, according to Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, a non-profit lobby group.

“A number of these factories that are under construction are quite large, and each of them employs, in some cases, thousands of people. Conventional wisdom . . . 15-20 years ago was that the era of big factories, particularly in the United States, was over.”

While previous manufacturing booms were in response to pent-up demand or war, this one “is significant because it is in response to both public policy levers and changing political, economic circumstances globally”, says Paul.

President Joe Biden’s policies have spurred foreign investment in semiconductor, electric vehicle and clean energy plants. But, after Covid disruptions exposed the risk of sourcing materials and parts far from home, many US companies are rethinking their production.

Increasing political risk in China and the impact of climate change on the transportation of materials and goods are also prompting companies to consider shortening supply chains.

During the pandemic, “we really learnt that resilience and domestic provision are valuable and the previous 30 years emphasised exactly the opposite point,” says Suzanne Berger, a US political scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Making in America. “Zero inventory . . . that Toyota system goal . . . means zero resilience.”

Since the Covid outbreak, mentions in companies’ earnings reports of reshoring, onshoring and nearshoring have increased almost tenfold, according to the IMF. To Berger, what we are seeing is nothing less than the “reversal of globalisation”.

“Globalisation was very good for developing countries and particularly for Asia,” she says. “It has been very bad for liberal democracies. And part of what has fuelled the kind of polarisation that we see in this country is the loss of manufacturing jobs. So I think . . . [in] the push for the expansion of manufacturing — which you see both on the side of Republicans and Democrats in the US — there is a political driver.”

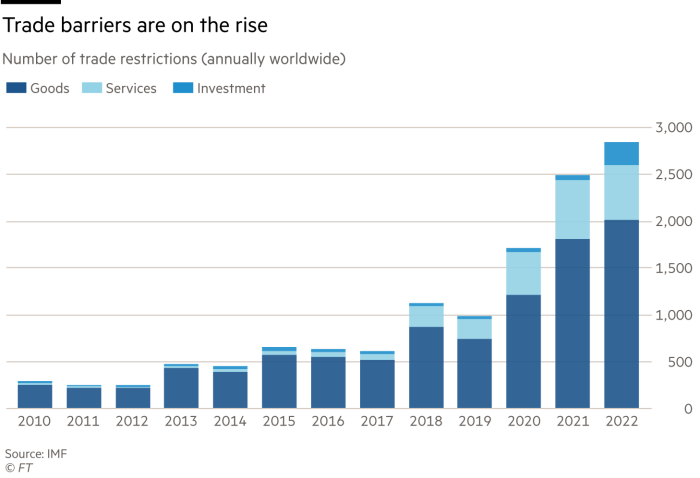

One factor spurring the localisation of production is what IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva called in January a “global surge in new trade restrictions”. In the US, the Biden administration has restricted investment in China’s tech sector, limited availability of tax credits for green vehicles to those produced in the US, and maintained tariffs put in place by his predecessor Donald Trump.

“I know that is very fashionable to beat on the tariffs that Trump put in place, but I think they also had a measurable impact in starting to reduce the level of imports that have been coming from China,” says Paul.

Though both sides of the political divide talk of reviving US manufacturing, consensus breaks down over how to achieve it. Several 2024 Republican presidential candidates have vowed to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act, despite the bulk of the investment being concentrated in Republican states.

“I don’t see why the government should have these industrial policies,” says Holtz-Eakin. “A reliance on letting the market allocate capital has been a very successful strategy for years and I don’t see any reason to change that basic input.”

A change in government would be just one barrier to making the boom sustainable. Consultancy McKinsey has also cited a shortage of the critical minerals required for clean energy, such as the rare earth elements needed for electric motors. And a more immediate concern is the tight labour market.

In July, chips giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company said work on its first US plant in Arizona would be delayed because of a shortage of workers. The Semiconductor Industry Association has warned that more than half of the 115,000 new jobs expected by 2030 would go unfilled because of a lack of skills.

Berger says there is a disconnect between the type of worker required by the average American factory and those produced by the country’s community colleges. This is due in part to a lack of advanced processes in domestic manufacturing, 90 per cent of which is done by small to medium-sized enterprises. There is nothing in the Biden legislation to change that.

Many older businesses “still have the milling machines that their grandparents had purchased for the company”, says Berger. The conundrum then becomes what kind of manufacturing will replace old postwar model.

“The big question,” says Berger, “is whether the manufacturing that gets built is just an extension of the kinds of manufacturing system that we have today in the US, which is low-tech, low-skill, low-wage, low-cost, low-productivity growth and high-carbon emissions, or whether we can build a new manufacturing system.”

Comments