Teaching children about money in lockdown

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Along with identifying different plants in the garden, calculating fractions and learning who Boudicca was, this week I’ve also been trying to teach my children about the value of money.

Like millions of working parents up and down the country, my husband and I became temporary teachers overnight after UK schools closed and lockdown began on March 23 as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

What has saved us are the abundance of online school learning programmes from the likes of BBC Bitesize, The Khan Academy and the new government-funded National Oak Academy, which is streaming 180 lessons per week. And, of course, there are YouTube lessons from celebrities such as PE with Joe Wicks, maths with Carol Vorderman and history with Dan Snow.

Yet it’s not just the traditional subjects that are being taught digitally — there is a wealth of material on personal finance out there too for children of all ages.

Experts say the lockdown is the perfect opportunity to give young people the financial skills they need for life. “Most of the previous generations — including millennials and generation Xers — were not taught about basic financial concepts, having to learn the hard way once they started working,” says Adrian Lowcock, head of personal investing at Willis Owen.

“This could be our chance to change that for the younger generations. While none of us would choose to be stuck in our houses for an indefinite period, we have an opportunity now to ensure something positive comes out of this crisis. Teaching our kids new things — including the value of money — could be a real benefit to them in the future.”

Whether you’re looking to introduce some formal lessons under lockdown, shake up your children’s savings or integrate learning about money more subtly into everyday family life, here is a wealth of ideas to inspire parents.

Start giving pocket money

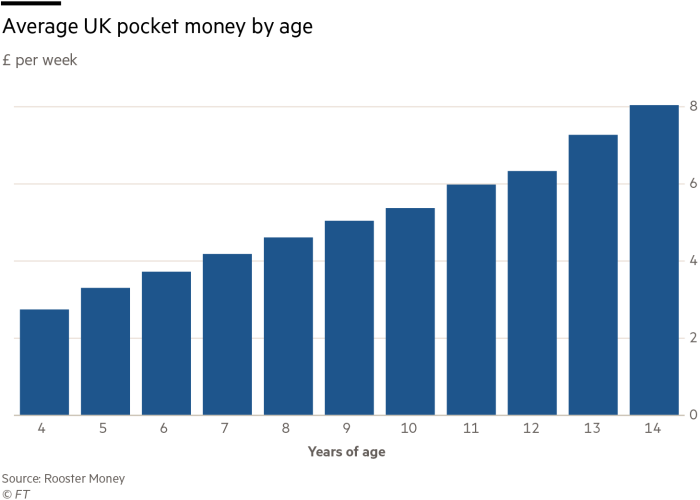

Whether it’s 50p or £5 a week, giving pocket money can help your children learn about budgeting as they start making decisions about their own money.

“It doesn't matter how much money you give your children, the act of paying regular pocket money helps open up conversations around money in the home,” says Louise Hill, co-founder of GoHenry, one of a growing number of specialist contactless card apps for children and parents.

Competitors include Rooster Money, Osper, Gimi and Otly. While fees and features vary, all of them help parents to educate children about the value of money while controlling what they’re spending.

The key, says Ms Hill, is to get children thinking about the four key pillars of money management: spend, save, earn, and give.

Make them work for it

As well as giving them weekly pocket money, parents can pay their children extra for completing tasks and chores — either via one of the above apps, or the old-fashioned way in cash.

The number one chore parents reward via the Rooster Money app is tidying bedrooms — and the most popular ways children spend their “earnings” are online computer games such as Roblox or Fortnite.

Parents may well have mixed feelings about monetising chores, but it can help youngsters learn where money comes from, that it has to be earned, and that it does not necessarily come easily.

Sarah Coles, personal finance analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, says children of any age can do chores for cash. “There are more of you making the place a mess at the moment, so more of you can clean up, and the kids can get some experience of earning money,” she says.

David Boyes from Wiltshire signed his eight-year-old daughter Ciara up for the GoHenry app and has been paying her to do chores. He says: “Within weeks, Ciara has learnt the value of money. Before, she would ask for things with no concept of what they cost. Now that she is managing her own money, Ciara has become very conscious of what is going in and out of her account.”

For smaller children, having a marble jar to fill — with the promise of treats when it is full — works well as a simple rewards system. Good behaviour can earn marbles — bad behaviour will result in the threat of marbles being removed!

Get them involved in household budgeting

Building a budget encourages children — and adults — to take a close look at their spending habits. This could be introduced from an early age via (an online) trip to the supermarket. Perhaps you could give them a set amount of money to see what they can buy on a budget. Older children could be challenged to make a meal — good practice for when they leave home, get a job or go to university.

“It’s very likely that we’re all going to be working and learning from home for a considerable time yet,” says Maike Currie, director at Fidelity International. “Take this opportunity to teach your children about money. You don’t need any textbooks — your kitchen (and lounge) is the best classroom.”

“During lockdown, people may be paying closer attention to family budgets and avoiding unnecessary spending,” says Becky O’Connor, personal finance specialist at Royal London. “This is a good chance to apply maths to real life.”

You could challenge children to find a better deal on mobile phone and broadband contracts, electricity suppliers or insurance and make them your in-house savings expert. To encourage them to do the research to find a deal, consider sharing some of the savings with them.

Dig out their old savings accounts

While stuck indoors, searching out paperwork and passwords for long-forgotten children’s savings accounts could be a profitable activity. The first wave of Child Trust Funds established by the then chancellor Gordon Brown will mature later this year, with about 400,000 teenagers becoming eligible to claim funds totalling around £700m.

CTFs were set up predominantly to invest in stocks and shares, so children will be able to see how their investments have performed over time — a great opportunity to get them interested in the stock market. You could also encourage them to transfer the money into an adult stocks and shares Isa when their account matures.

If you have set up a Junior Isa for your child, be aware that the annual tax-free savings limit has just been raised to a very generous £9,000.

For cash savings, challenge children to find out the rate of interest paid on old accounts, then research the best deals available.

Play games

Playing games is the easiest way to get children interested in money. You could try a game of Monopoly — there are important financial lessons within the game, such as the importance of always keeping an emergency fund, managing cash flow and honing your negotiating skills. It naturally brings out lots of discussion (and arguments) over money and being the banker is great for maths and mental arithmetic.

Older children and young adults could try their hands at the FT’s Road to Riches board game, where they will be faced with financial dilemmas including whether to prioritise saving for a house deposit over saving into a pension.

The power of saving

Saving pocket money towards a longer-term target helps teach children that resisting the temptation to spend immediately can lead to bigger rewards.

“For older children, you could promise to pay them a ‘bonus’ if they hit an agreed savings target. Or you could offer to double any money they are prepared to put aside into savings,” says Ms Coles. “This will show them the benefits of saving towards their goals.”

This could also give you an opportunity to explain how long-term savings vehicles such as Junior Isas work, and how the investments within them can help generate more money in the long run.

Top 10 things UK youngsters spend their money on

1. Roblox

2. Fortnite

3. Books & Magazines

4. Lego

5. Sweets & Chocolates

6. Xbox

7. Minecraft

8. Toys

9. Apps

10. PlayStation

Source: Rooster Money

Top 10 paid chores for UK youngsters during the lockdown

1. Clean bedroom

2. Make the bed

3. Do the laundry

4. Clear the table

5. Look after pets

6. Set the table

7. Empty dishwasher

8. Homework

9. Load the dishwasher

10. Take out the bins

Source: Rooster Money

Watch and learn

The internet provides many fun — and free — ways to teach your children about money.

The KickStart Money programme is proving popular with parents and was set up after research found that our money habits as adults are set by the age of seven.

Aimed at improving financial education among children aged between five and 11 using videos, games and quizzes the initiative is funded by 20 financial companies and overseen by charity MyBnk.

Its financial education programme, Family Money Twist, is an easy way to encourage the youngest members of the household to learn how to save and spend responsibly — with help from the Cookie Monster and a Save-o-saurus Rex. Its programme for 7-11 year olds launches on May 11.

Steve Korris, father of seven-year-old Matilda, has been using Family Money Twist to introduce money to her and to start conversations about money at home. “At school she has learnt coin recognition and maths sums, but nothing about how money works, value, income and savings,” he says. “She’s very inquisitive so will definitely be asking questions now we’ve got her started.”

Another great free resource for teachers (which has been adapted for home schooling) is the website of the Young Money charity. Parents can download free home learning guides covering everything from spending and budgeting to how student loans work.

Children aged 4-19 can sign up for the Young Money Challenge and win £50 for themselves (and up to £500 for their school). This year’s theme is how to be a responsible consumer, and entries must show how they’re reducing energy use, upcycling items or avoiding food waste.

Delayed gratification

One of the most important habits to develop and practice is finding ways to delay spending decisions. Many things that children (and adults) want badly in the moment seem less crucial if they just delay the purchase and sleep on it.

“Telling kids that they can have that thing they want, but only if they still want it in a day, or a week, is a technique that resolves a lot of impulse spending,” says Greg Davies, head of behavioural science at consultancy Oxford Risk.

The length of time it takes to save up for something is a powerful indicator of its value for children who are old enough to receive pocket money. Tell them to divide the cost of the thing they want by the amount of their weekly allowance to work out how many weeks it will take them to save up for it.

Get in touch

How have you been teaching your children about money under lockdown? Leave your comments below or email the Money team via money@ft.com we will print a selection of the best reader ideas next week.

“The thought of, say, eight weeks of waiting gives context to £40 — and might just put them off the item,” says Ms O’Connor. However, be prepared for more enterprising children to ask for a pocket money pay raise.

Another way of connecting time and the value of money is to divide large items up into the number of days you and your partner have had to work in order to afford them.

“This way, they learn to equate the worth of possessions according to effort and to view things they want as reward for work,” says Ms O’Connor.

“If you explain to your child that it takes three days of work to earn, say, one PS4, they are able to understand the value of the item is more than a set of numbers. Do this with the value of houses and cars — calculating after tax for greater effect — and watch their mouths open in disbelief.”

Set the example

“Never underestimate the impact your own money habits — good or bad — will have on your children,” says Ms Currie. “Describe what debt is, and the downward spiral that it can be for so many people.”

You can talk to your children about your own experiences and interest rates associated with different financial products. This will be particularly beneficial to older children who might be about to take on student loans.

“If you teach them nothing else, make sure they have a firm understanding of the two Cs: compound interest and credit cards,” she adds. “If they understand the magical power of the former and the dangers of the latter, you’re halfway there.”

Talk about money

In the current environment you may want to have some financial discussions in private, but in general, it’s great to show youngsters that money isn’t taboo by talking about it openly.

However you try to teach children about the value of money the key thing is not to make it boring, says Ms Coles. “You can do more harm than good if you march them through a preset lesson under time pressure and with you both in a state of high stress.

“If you have time to teach your kids about money, this is a brilliant opportunity to do so, but if you don’t have time or space for it, then the hands-off methods may make a great deal more sense.”

Why money matters

Financial education will undoubtedly have an important role to play in preparing children for an uncertain future, says the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), warning that young people stand to be the most economically affected by the after-effects of the pandemic.

A lack of preparedness for the unexpected has shown that money lessons matter, says Greg Davies, head of behavioural science at consultancy Oxford Risk.

“Levels of financial resilience in the UK are extremely low, with large portions of the population with little or no savings buffer to help tide them through unexpected emergencies,” he explains.

He points out that a large proportion of the UK population lack the functional skills and knowledge effectively to manage their money.

“Since we’re now in the midst of such an emergency, the importance of financial resilience and financial capability is becoming painfully apparent, and for many people simultaneously,” he says.

However, building financial capability takes time, and requires developing effective money management habits. “The earlier such behaviours can be inculcated, the better,” he adds.

Even though many young people say they wish they had learned more about money and finance at school, it has never risen far up the agenda.

Myron Jobson, personal finance campaigner at Interactive Investor, says: “In a packed curriculum, financial education competes for space with many other topics and it is not compulsory in academies, private schools or faith schools. But with many families now taking a much more hands-on role in home learning, there’s more flexibility to talk about money management.”

Will Carmichael, chief executive of RoosterMoney, adds: “Now more than ever, building financial capability into our kids is so incredibly important. The current pandemic and the financial impact of the crisis are likely to affect us for a generation. Having confidence with money, building positive habits around saving and learning to make considered spending choices will be skills that stick with them for life.”

Comments