Cristiano Amon: generative AI is ‘evolving very, very fast’ into mobile devices

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Cristiano Amon took over as chief executive of Qualcomm, the world’s largest mobile chipmaker, in 2021, just as the semiconductor industry was struggling to navigate pandemic-wrought supply shortages.

Three years later, the semi cycle has swung back and the chip market is only beginning to emerge from a glut. Consumer spending on smartphones — Qualcomm’s core market — and other consumer electronics has slowed at a time of high inflation and maturing handset technology.

Amon, a Brazilian-born engineer who first joined Qualcomm in 1995, has tried to diversify the San Diego-based chipmaker into new areas, including PCs and cars. But while its share price rose by about a third in 2023, its ties to the sluggish mobile market held its stock back from the artificial intelligence-driven boom enjoyed by the likes of Nvidia, AMD and Intel. Those chipmakers benefited as cloud computing providers retooled their data centres for “generative AI” tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

As he explains in this interview, Amon sees that changing this year, as AI arrives on mobile devices in a big way — and, he believes, brings sweeping changes to the balance of power in an industry that has long been dominated by Apple and Google.

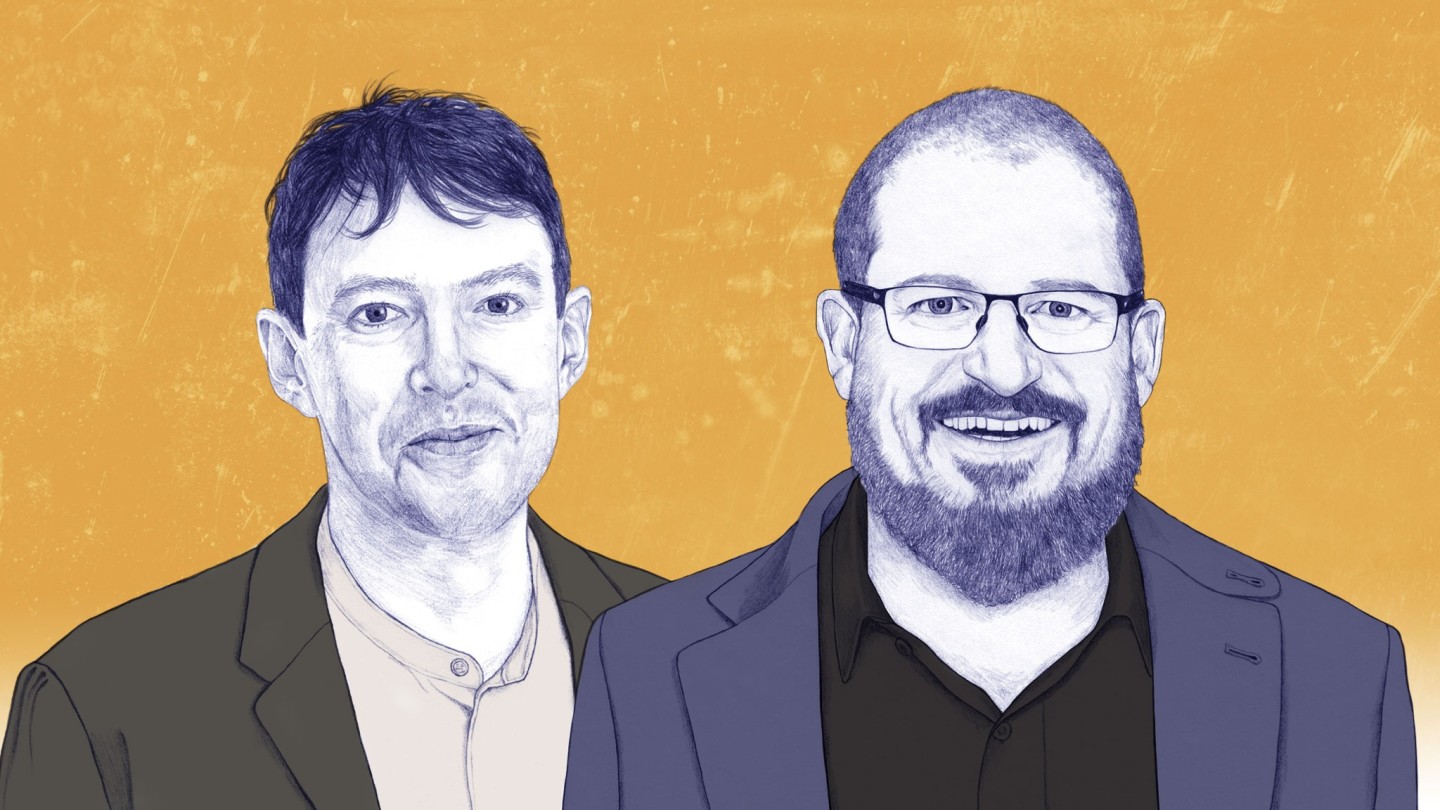

Tim Bradshaw: It feels as though, for the past year, all the conversation about generative AI and chips has been about what’s happening in the cloud. Do you feel like that’s about to change in 2024?

Cristiano Amon: Oh, it is going to change. It’s already changing, actually. And for a number of reasons. This is not about [everything that happens in] the cloud moving to the device — I think the cloud will continue to be very relevant, will continue to evolve, it’s going to be indispensable. But the device has a different role to play. And we see now gen AI evolving very, very fast into the device. I think that has been the history of computing: you start with things in the cloud, or in the mainframe in the past, and then, as the distributed computing capacity exists, you start to see the same type of computing moving on to [smaller] devices [like the PC and mobile phones]. We’re about to start that transition in a big way [in AI].

Tech Exchange

The FT’s top reporters and commentators hold monthly conversations with the world’s most thought-provoking technology leaders, innovators and academics, to discuss the future of the digital world and the role of Big Tech companies in shaping it. The dialogues are in-depth and detailed, focusing on the way technology groups, consumers and authorities will interact to solve global problems and provide new services. Read them all here

TB: And is that shift away from the cloud enabled by changes that you and other chipmakers are making, to squeeze these huge AI models on to smaller devices? Or are the models themselves changing so they can run on different kinds of computers?

CA: It’s all of the above. We [now] have the ability to create a high-performance AI processor that can be on a battery-powered device. They can run all the time, they can run pervasively. That’s the first element: having the computing engine that makes it a reality. But then the second thing that is happening is that models, as they are [becoming better-] trained, are becoming smaller and more efficient — especially if the model is for a particular use case. And that is coming to [portable] devices. Number three is that the applications are now being developed to make use of this capability. So you put everything together, and you see that will happen in phones, in PCs, in cars and even [other devices like] your WiFi access point, for example.

TB: How do you think this will show up for consumers? What will people notice as the biggest difference in an AI-enabled phone compared with how they use one today?

CA: When you’re thinking about gen AI running on devices, it is going to happen in at least two ways. One way is that you will have an AI that is running pervasively, and the job of the AI is to predict your every movement — to sort of predict you. That is very, very different to the cloud, where you have to go and run a query [ask a question to get a response].

The second way is doing the same thing that happens in the cloud, in conjunction with the device. We call that hybrid AI. So you can actually make it more affordable [for the developer] to run the AI because you’re using the computing power [on the device instead of having to call up to the cloud]. And you can make the AI more precise, because the device has real context about what you’re doing, where you are, etc. So those are two ways.

TB: Can you give me more examples of the first one, about how AI will change the user experience of the device?

CA: Let’s just go to something that you probably do multiple times a day: texting. When you write a text, you think about it as a message that you are sending to another person. But for the AI, that could be a query. As you type that text message, the AI is running and thinking, “Is there something for me to do here?”.

You just said that you want to get on a call with Clare next week and you suggested Tuesday, so the AI will bring up the calendar app and say, “Tim, you have these slots available. Do you want me to send a calendar invite to Clare?” The other kind of thing that is going to happen is: you tell me that you just had a wonderful holiday with family, and as you mention this, the AI is going to say, “These are the photos you took, do you want to share that with Cristiano?”.

TB: People have tried that kind of thing in the past and often it was just kind of annoying. I’m thinking of Clippy, the virtual assistant that featured in Microsoft Office apps 20 years ago, saying things like: “It looks like you’re writing a letter, would you like help?” Why do you think it’s going to work better this time?

CA: Because it’s going to be more precise and it’s going to learn your behaviour, about what you want and what you don’t want. Remember, it was not possible to do it in the past because there was difficulty interpreting your language. It was difficult to get context and you had to program every move. You don’t have to program any more. That’s why you have these large language models [the systems powering AI assistants today]. And the other reason is that you now have the ability to run AI pervasively, about everything that you do on your screen, as an example.

TB: How much faster is it going to feel to the user when you’re running AI on the device itself, compared with waiting for the data to be sent to and from the cloud when you’re using an app like ChatGPT today?

CA: It has to happen in seconds. Let’s switch from large language models to large visualisation models. Are you familiar with Stable Diffusion? You type a text query and it creates a photo . . . We have demonstrated Stable Diffusion running in 0.6 seconds on the device. So it’s [changing] your everyday user experience: how you think about taking photos, how you think about editing photos.

TB: What does all this mean exactly in terms of the silicon content inside each phone?

CA: We’re developing separate computing [processors] for AI. Because you can run things on a CPU [central processing unit], you can run things on a GPU [graphics processing unit], but the GPU and the CPU on your phone are busy doing other stuff. So if you’re going to run AI pervasively, you want to have dedicated accelerated computing — that’s why we also have the NPU [neural processing unit].

TB: Other than smartphones, where else will we see gen AI changing how we interact with our personal devices?

CA: The car is even easier to understand because when you’re behind the wheel, natural language is not only a safe, but also good, way to interact with your car. The car will look at your calendar and say, “Here’s where you need to go, I’ve already programmed that navigation for you.” Or it might say, “I’ve noticed that you always call somebody, you call your wife or your friend, do you want me to call them for you? I know that you have to buy groceries, do you want to make a stop at the grocery store?” Large language models are going to be perfect for the user experience in a car.

TB: For your customers, the device makers and electronics manufacturers, how much do you think AI has the potential to change the competitive landscape?

CA: We’re just at the beginning of this, where you are starting to see OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] talking about different user experiences on their devices. Some are gravitating towards photography, some are gravitating towards communication and translation. Some are gravitating towards productivity.

TB: How far do you feel like all of the things that you’ve talked about are going to rekindle growth in the smartphone market? Will consumers pay a premium for AI features, or is it just going to be something they expect as a standard part of the toolkit?

CA: This is a multi-billion-dollar question. You’re going to see devices launch in early 2024 with a number of gen AI use cases. It has the potential to create a new upgrade cycle on smartphones. And what we want is that eventually you’re going to say, you know, “I’ve been keeping my phone for the past four years . . . Now I need to buy a new phone because I really want this gen AI capability.” And you’re going to have to buy a new phone because it’s about the computing engine which is coming on those new platforms.

TB: The industry needs something to spur sales because it’s a mature market now. It’s been a tough couple of years for the smartphone makers.

CA: We were very pleased in the last earnings that the inventory dynamics and the correction of the phone market we saw in 2023 on Android are behind us now. I think the market has found its point of stability. We’re being cautiously optimistic. We’re assuming growth [in 2024] . . . But it is a mature market in many aspects, so when it grows, it grows in single digits.

However, there are different things happening in the market which are important to point out. When you go buy your new phone, you look to buy a better phone than you had before. So we have seen premium and high tiers have a higher growth rate as the market goes into a replacement cycle than the lower tiers. That’s a healthy metric. Over time, if we create a replacement cycle driven by gen AI, that will significantly change the size of the market — especially because then upgrade rates are going to [accelerate], and we’ll be able to see a lot of growth potential. I think right now, we’re just happy we’re stabilising.

TB: When we talk about these big AI models, there are really two roles for chipmakers: processing all the data upfront to create the models, which is known as “training”, and then there is how models are put to use in applications, which is called “inference”. So far in AI, the market has really been all about training and Nvidia has been by far the biggest beneficiary of that. What do you see as the relative opportunity for chipmakers in inference versus training going forward? Which is going to be the bigger market long term for semiconductor companies?

CA: It’s pretty logical, I think. A lot of the infrastructure on AI, especially for gen AI, started in the cloud, with a particular [chip] architecture that you needed to do training. But when models become smaller, they run on a device, they become specialised for a certain task. So what’s going to gain scale, in gen AI and in AI in general, is inference. Because that’s what you do: you train it so you can do inference. So even in the data centre, we have started to see a lot of interest in dedicated inference processors for models that are already trained and you want to run them at scale. So it is inevitable that inference is going to surpass training. When you talk about devices, it is all about inference.

TB: Running AI apps like ChatGPT right now is quite expensive for companies such as Microsoft or OpenAI because each time a customer uses the app, it incurs computing costs. How does doing AI on-device change the economics of that?

CA: When you think about AI models, they’re coming to devices. A number of different models are being ported to Snapdragon [Qualcomm’s mobile chip platform]. I think [mobile] platforms are becoming more open, with more potential for innovation.

We [think] a hybrid model is going to be important, especially if you look at the high cost and high energy consumption of the data centres with gen AI. You want to be able to make use of distributed computing. A lot of the models that you see today are running on the cloud. But if there’s an inference version of that model [installed] in the device, the device will give the cloud model a head start. When you make a query on a device, it is way more precise, because the device has real context: where is Tim? What was Tim doing before? So the result is that this hybrid model is cheaper. Because when you leverage the computation on the device, the query is more precise and it’s actually a more efficient way of doing computing [than running AI apps in the cloud].

TB: Can you give me an example of how that might work?

CA: Let’s say that you’re using Bing Chat [Microsoft’s AI assistant, powered by OpenAI’s GPT model]. Let’s say you have an Android phone, and you have your Edge browser, and you go to Bing and you start a chat. Today, you type in the chat box and that query goes 100 per cent to the cloud, and the cloud is going to run GPT and you start to see your answer being displayed in a string [of text]. Microsoft is paying the entire cost of that computation in the cloud and it is not cheap and it consumes a lot of energy.

Fast forward [to the new kind of AI devices] and you have now an instance of GPT or some other model from Microsoft that is running on your device. It is installed on the NPU of your device. Then you open the same Edge browser and you make the same query [to Bing chat]. The first model that runs is the model on your device. And it starts to do some computation, it generates some tokens, it sends them to the cloud. The cloud now has less computation to do to give you the answer. Or the model could say it feels well enough trained to just answer itself — then the cloud doesn’t have to do any computing. It is still a Microsoft service, but they’re now making use of the computing [power] that’s available in your phone.

TB: OK, I can see how that will be cheaper for the AI company or cloud provider. But today, the companies building and running the biggest AI models — like OpenAI and Anthropic, and even Microsoft, Amazon and Meta — aren’t necessarily the same companies that make smartphones and their operating systems, which is where companies such as Apple, Google and Samsung have more of the control. How do you get all of that to line up so the right models are in the right places?

CA: Bingo. I think that’s a great question. And that’s why I said that the platforms are changing.

If you think about [mobile] platforms today, you have one platform and one OS [operating system], and the only thing that runs is what’s on my OS. But that’s going to be different. So let’s just use an example. Let’s say you have Microsoft Copilot [the company’s AI chatbot assistant] that is running on Outlook, or Word, or some other application in the cloud. But you also have that Microsoft application on your device. Your device could have access to a third-party gen AI model from Microsoft that is running on the accelerated computing [chip] on the device. In that case, the provider of that service to you, the Copilot, has an instance on the cloud and it has an instance on the device.

Now let’s change [the example] to Meta. You have a Llama 2 model [an AI developed by Meta] on your device. You have an application for Meta, let’s say Instagram, you have that on the cloud and on the device. So this is a big change, especially when you think about the computing engine and the access of those models by applications. This is fundamentally changing, I think, how the industry works.

TB: So you’re saying that, by pushing their AI models into more phones, companies like Microsoft and Meta may get a chance to regain some of the influence in the mobile industry that they lost when Apple and Google won the smartphone OS wars? But for that to happen, don’t you need alliances between handset makers, OS makers and application developers that are not currently always that friendly?

CA: That’s why I think the industry is changing. For an app, you have an App Store. But when you run a gen AI model on the device, it is going to be pre-installed on the device engine, it’s not something you’re going to download from the App Store.

You’re going to see the ability of [mobile] platforms to support first party and third party models, as well as the OEMs. The way to think about this is like the camera app. The OEM builds that camera capability into the device, and you’re going to have a number of different engines that are built into the device as well.

I think that part of the industry is evolving. I understand the question, but you also have to think about what users want. That’s why you’ll see that you’ll have so many different apps, even apps from competitors of the [mobile] platform, and I think we’re just at the beginning of that transition.

TB: How might Qualcomm benefit from all this?

CA: The first thing is, you will make the phone market bigger. That has a benefit to our chip business and to our licensing business. A gen AI-capable device requires more computing power. That has two aspects. It drives a mix improvement towards you buying a higher premium device. It also has more silicon content, which also drives more margin contribution for the business.

That’s how it happens on the phone. On PC it is completely different and it’s an incredible opportunity. We’re entering the PC space. We are the company that Microsoft selected to do the Apple compete platform. [Qualcomm and Microsoft are working together to produce PCs that they hope can outperform Apple’s Mac computers.] When you think about the transition of Windows to gen AI, that’s an incredible tailwind for our PC entry, because we are coming in with the leading AI processing capability by a long shot. We have the best-performing part with the lowest power consumption.

The other [opportunity] is automotive. We have built a very strong position in automotive with our Snapdragon digital chassis and the immersive digital cockpit. Qualcomm has become the de facto platform of choice for all of those new immersive digital cockpit experiences that you see across over 30 brands. Gen AI capabilities [promise to let us] upgrade the system with more value to our customers and consolidate Qualcomm’s position in the automotive industry.

TB: All the hype in Silicon Valley right now is about AI. Not long ago it was all about the metaverse and virtual reality, which hasn’t panned out to be quite as big as people hoped. How do you see the potential to bring these two trends together?

CA: We are seeing gen AI coming into VR. We see an incredible potential [for augmented reality and mixed reality glasses], especially as you use audio and large language models as an interface. We have been very bullish about spatial computing being the new computing platform, and we see a lot of promising developments coming: we see what Meta is doing, we see what is happening on the Android ecosystem with Google and Samsung. We are just at the beginning.

TB: You’ve supplied the chips for new kinds of lightweight wearable device, such as Meta’s Ray-Bans, that rely less on immersive visuals and more on audio AI assistants. Might this be the disaster of Google Glass all over again, or could they be more popular than the full-on VR experience in the near term?

CA: I would bet on lightweight wearables every time. It was not until the smartphone that you started to carry a computer with you all the time. There are two things that are going to drive usage and volume. One is that [products] get lighter and easier to wear, so you wear them for longer. The second is content. As you bring more capabilities to those devices, you have better content. I think we are on that trajectory. More scale gets even better content, because developers are willing to invest the money.

The glasses that we just launched with Meta, the Ray-Ban glasses, they are very useful for a number of applications, especially as you think about social media and how you generate content. They are going to get better.

TB: My last question is about foldable phones, which have been a bright spot of growth in a dismal year but are still selling in very small numbers overall. Are folding phones going to make it?

CA: Of course they are going to make it. [Holds up his Samsung folding phone.] This is my Flip number four. I don’t think I’ll go back to a non-foldable. It’s incredibly useful.

TB: And that’s really your everyday phone?

CA: Absolutely! This is an uncompromised phone. It has all the performance you need. It fits better in your pocket. And there’s nothing wrong with opening to answer a call and folding it to end the call, especially for somebody like me that started to use phones in the ’90s.

The above transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity

Comments