How AI eases teachers’ heavy workloads

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In a primary school in Plymouth, England, children sit across from Nao, a humanoid robot that is conducting an educational game using an electronic tablet. The machine, created by the robotics arm of Japan’s SoftBank, is capable of recognising 20 languages and learnt how to conduct the lesson in three hours.

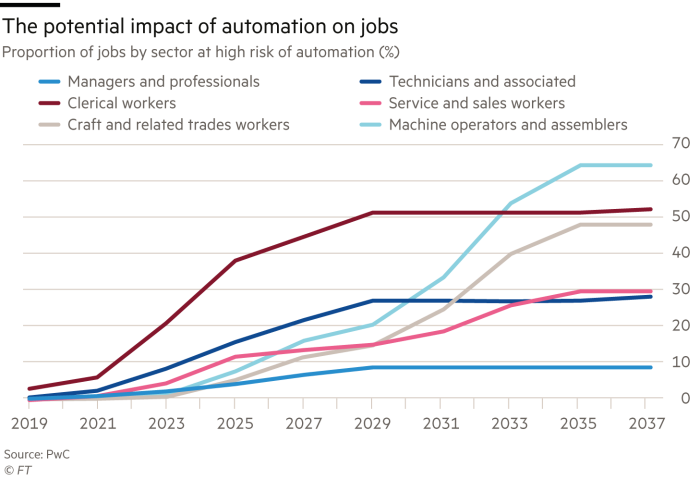

Nao and other advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics have raised concerns that human teachers could one day become redundant. It is estimated that 1.5m workers in England and 800m globally are at risk of being replaced by robotic automation by 2030, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics and McKinsey Global Institute.

Experts, industry chiefs and governments say such fears are overblown, and are working together to harness technology to ease teachers’ workloads, freeing them from mundane tasks to focus on spending more time with their students.

“Too much of our time is spent planning lessons and assessing students,” says Isabella Kallan, a modern language teacher in London who has witnessed Nao in action. “Schools need to employ more teaching assistants but the government hasn’t provided the resources. Technology like this would enable us to help more of those students who are struggling.”

A quarter of teachers in England work 60 hours a week, according to a recent University College London report. The overall average was 47 hours during term-time, which is eight hours more than comparable OECD countries.

While 98 per cent of teachers say they enjoy teaching, they spend less than half their time in the classroom because of the burdens of administrative work, planning lessons and marking, according to a report by Ofsted, the government’s inspectorate.

More than a third of UK teachers leave the profession within five years of joining and almost half have experienced depression, anxiety or panic attacks due to workload. The sheer amount of work has been identified as one of the main sources of teacher stress, with marking especially described as “heavy” or “massive”, says the report.

“More and more teachers are leaving the profession,” says Jake O’Keefe, co-founder of Atom Learning, a platform that helps teachers with planning lessons and gathering resources. “It’s about the quality of the work and the stress put upon them both internally and from parents.”

The UCL report recommended a cut in workload and less time spent on lesson planning and administration. However, it added that these recommendations will be difficult to implement without technology because teaching assistants are already overworked and there is a shortage of teachers.

“Tech . . . can empower the teacher to spend more time teaching, freeing them up to focus on skills like critical thinking and collaboration,” says Priya Lakhani, chief executive of Century Tech, a learning platform for schools and universities.

Century Tech’s system marks each student’s work automatically, collecting the data for teachers so they can identify who understood the lesson and who struggled. Funded by angel and social impact investors, it charges £5 a year per pupil, and invests revenues into research.

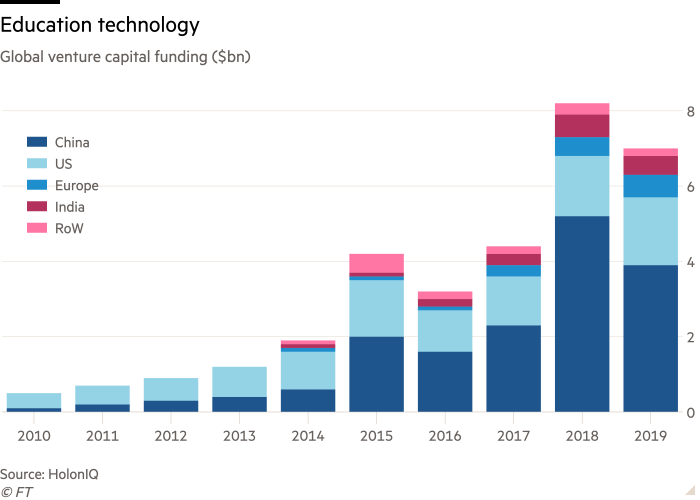

Investors generally continue to be enticed by education technology companies such as Century, with venture capital funding for the sector surpassing $8bn in 2018, according to Holon IQ, a market intelligence agency. Think and Learn, the Indian company behind learning app Byju, was recently valued at $8.2bn following fresh funding of $200m from US private equity group General Atlantic.

Elon Musk, Tesla chief executive, once described AI as “our biggest existential threat” and likened AI research to “summoning a demon”. A recent report from the Institute for Ethical AI in Education, a UK based think-tank, warned that replacing emotionally-laden teaching and learning activities with algorithms could decrease independent thinking and depersonalise education, while personal user data could also be used inappropriately.

Ms Lakhani is conscious of these risks. However, she is sure of one thing: “Technology cannot and will not replace the one to one interaction between the teacher and the student . . . The idea that kids will walk into schools run by robots and machines is nonsense.”

Comments