Business success is about serving basic human needs

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is part of the FT/ArcelorMittal Boldness in Business awards, recognising companies and individuals with novel answers to everyday needs.

Even the most complex and innovative business succeeds because it serves human needs that are simple and unchanging. This is an easy truth to lose sight of, but this year’s Boldness in Business Awards illustrate the point beautifully.

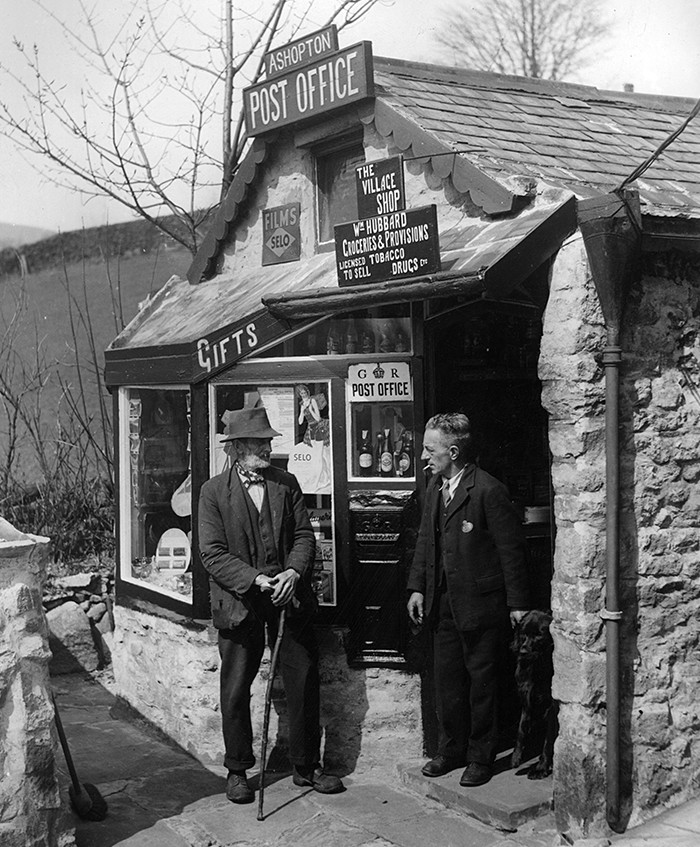

To understand why, let us imagine a very simple, self-contained economy — a village, of the sort that was common all over the world a century or so ago. It is a farm town, though it could as well have grown up beside a little factory or a mine. The town’s businesses and professionals are easy enough to add to our picture. Here is the one-room schoolhouse, there the doctor’s office and the tailor’s shop; the little local bank, a little row of shops.

Depending on the continent and country your family comes from, the details of your imagined village will vary. Whatever the details are, I hope you are now in the grip of a nostalgic feeling for the sort of place where perhaps your great-grandparents spent their lives (or you imagine they did).

Hold on to that warm feeling. I have just described to you this year’s winners: schoolhouse, doctor, tailor, bank, a couple of grocers. Does the line-up, so described, strike you as lacking boldness? It should not. Again, all companies serve unchanging needs. Boldness consists in serving them in a way others overlooked, doubted or dismissed.

Let us start with our schoolhouse (and Drivers of Change category winner) Byju’s . The image of the single-room village school is particularly apt for a business that began as a one-man proprietorship. Byju Raveendran started out as an exam tutor and, less than a decade ago, founded the company that provides video tutorials.

The need for consistent, high-quality education has always been there, especially in the developing world. What is new is seeing that this need can be served at low cost using a combination of technology and pedagogical technique — even in a physically vast, polyglot country such as India, where internet access and financial infrastructure are uneven.

Big-name global venture investors are betting that what has worked in India can work across the world, as Byju’s expands to the US, the UK and elsewhere. The little schoolhouse now has 40m students (including 2.8m fee-payers) and, in a recent fundraising, a valuation of close to $8bn.

The schoolteacher in our village has something in common with the local doctor. Both Byju’s and the winner of this year’s technology award, Healthy.io, are tackling very old needs that have been especially resistant to modern efforts at improving efficiency. The economies of scale found in manufacturing, technology and finance have proven maddeningly elusive in education and healthcare.

Healthy.io is using smartphone technology to move a medical process — urinalysis — out of a high fixed-cost setting such as hospitals and labs into the home. A simple test kit, using a smartphone camera and some diagnostic software, has the potential not just to bring testing costs down but to eliminate millions of visits to medical facilities. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved the product, and the judges were happy to see smartphone technology moving from selfies and social media to solving more fundamental problems.

To compare Levi Strauss as a tailor’s shop may seem a reach. Perhaps the most famous clothing brand in the world, it has annual sales of more than $5bn. With its core product broadly unchanged for a century and a half, to call it bold may seem a stretch, too. But it was precisely because Levi’s is a big company, steeped in tradition and in an ancient industry, that the changes it has made have impressed the judges, who awarded the company with this year’s Corporate Responsibility and Environment award.

Levi’s has a long tradition of good corporate citizenship, but under chief executive Chip Bergh the company has faced new pressures, of both public ownership — the family-controlled company listed its shares last year — and a changing industry. But it is not overcoming those challenges by short-changing its employees or the environment.

The standard way to control costs in the garment industry is by outsourcing production to poorly regulated suppliers that externalise human and environmental costs. The dying and “distressing” of jeans present particular hazards, as explained in Dana Thomas’s excellent recent book Fashionopolis. Thomas singles out Levi’s for rejecting unsustainable approaches.

Sometimes it is also bold to stick to an older, better way of doing business: treating your customers and workers as if they were neighbours in your village.

Nubank , honoured this year for entrepreneurship, has achieved something extraordinary. Start-up online-only banks are common enough, but very few have gained traction. Unlike education and healthcare, banking is an industry where economies of scale are everywhere, putting newcomers at a disadvantage. The costs of complying with banking regulation make it harder still for the upstarts. Nubank, though, is growing fast — it has more than 20m customers — and is doing so in a Brazilian market dominated by a handful of big banks, several of which are controlled by the state.

Nubank’s main innovation? Offering a better product: a no-fee credit card with market-leading interest rates. The idea of giving customers a good product at a fair price might have come from a small-town banker — perhaps Jimmy Stewart’s character in It’s a Wonderful Life. But Nubank’s simple business idea is paired with the audacity to believe a young company could take on an oligopoly and win.

There is no doubt that raising insects for protein is a futuristic-sounding business. But it is a permutation of farming, one of the oldest businesses of all. Ÿnsect took this year’s Smaller Company award because if it can do what it says it can — produce cost-effective animal feed that is high in protein with much lower environmental impact than traditional methods — it could change the economics of the way we eat for the better.

Finally, our village shopkeepers. The fight of bricks-and-mortar retailers to thrive and innovate in the age of Amazon is a theme that has interested the judges for several years. VkusVill (“Tasteville”) took the Developing Markets award this year for proving that a food-retailing model combining high quality and deep vertical integration can work in the tough Russian market. Its $1.3bn in annual revenue and 1,200 stores are a testament that demand for locally sourced, fresh products is hardly restricted to markets such as the US and the UK. People want to know where their food comes from, and prefer that it comes from nearby.

The idea that the chief executive of Tesco would receive the Boldness in Business Person of the Year award would have been hard to fathom just five years ago. The supermarket group was seen as having expanded too much — both in the UK and globally — just as its business model was being overtaken by discounters and overturned by home delivery. A criminal investigation into the company’s accounting practices piled on more pain.

But since taking the helm at Tesco in 2014, Dave Lewis has proved the company is not obsolete yet. Costs have been reined in, unprofitable stores closed, and the product offering changed to bring back customers lost to the big discounters Aldi and Lidl.

Part of being bold is seeing a business in all its simplicity. A food retailer needs to have the right product, sourced at the right cost and sold at the right price. What Lewis demonstrated is that changing technology, new competitors and internal struggles cannot be allowed to distract from that basic equation — an equation village shopkeepers have understood for centuries.

Nominees

Drivers of Change

Hitachi

The Japanese group has, over the past decade, enacted an aggressive restructuring plan to shed non-core assets while expanding overseas. A corporate governance shake-up has set it apart from other Japanese conglomerates.

Microsoft

The company was at risk of technological irrelevance but its chief executive has presided over an era of rapid wealth creation starting with its focus on cloud computing.

Northvolt

The Swedish start-up is building Europe’s first factory for lithium-ion batteries and is open to tie-ups. It raised more money than any other European start-up last year, pulling in €1bn.

Signal

Signal is considered one of the most secure free end-to-end encrypted messaging and voice-calling apps. Despite widespread adoption of its technology, the organisation behind Signal employs fewer than 10 people and relies on grants and donations.

Waterstones

Since almost going out of business nearly a decade ago the UK bookseller has reinvented itself under chief executive James Daunt, proving there is still life and profit to be found in high-street retailing.

Corporate Responsibility/ Environment

Aquafil

The Italian manufacturer of synthetic fibres is best known for Econyl, a recyclable nylon fabric made from nylon waste. The company turns old fishing nets, carpets and the like into new swimsuits, watch straps and outerwear.

IBM

IBM started its P-Tech initiative in the US to create schools that offer mainly low-income students a six-year engineering course and preparation for Stem careers. Completion rates of graduates are five times the US national average. There are now 204 such schools in 18 countries.

Milk & More

Britain’s largest doorstep delivery service for bottled milk and other locally sourced premium products, is owned by dairy supplier Müller. About 97 per cent of deliveries come in reusable, recyclable or compostable packaging. Since the start of 2019, Milk & More has gained 85,000 new customers.

SSAB

The Swedish steelmaker has ambitious plans to decarbonise its production process by using hydrogen — an expensive and commercially uncertain proposition. Emissions from “green steel” would be water vapour rather than CO2. By 2025, the company aims to cut its emissions in Sweden by 25 per cent.

Stella McCartney

The owner of the eponymous label has been a pioneer of sustainable fashion, eschewing animal products such as leather, fur and skins. Last summer, LVMH took a minority stake in the brand.

Technology

Babylon Health

The UK company has developed a chatbot app that checks patients’ symptoms. It also offers a service connecting patients in London to doctors by smartphone video call. Babylon plans to bring the GP at Hand app to Manchester in 2020.

Brainomix

The medical-technology start-up’s AI-powered software analyses CAT scans to improve the diagnosis and treatment of strokes. A score indicates the severity of the stroke, while colour markings on attached images pinpoint the affected areas of the brain. In 2017, Brainomix partnered with drugmaker Boehringer Ingelheim to offer its software in 1,500 stroke clinics across Europe.

Local Motors

The US manufacturer designs collaboratively and produces vehicles in low volumes, largely by 3D printer. It has solicited designs for a low-speed, rugged, electric vehicle intended for island economies. It has announced a 50/50 joint venture with Airbus to build drones and self-driving cars in Munich.

Neuralink

Founded by Elon Musk, the US neurotechnology company is developing neural interfaces to transmit data between human brains and computers. It plans to surgically embed electrodes to turn neural recordings into electrical signals and feed them to a robotic device, which in turn can aid patients’ movement or vision.

Verily

Alphabet’s life sciences unit is focused on harnessing big data to predict and prevent disease, often through partnerships with healthcare companies and universities. It has developed a machine-learning platform to diagnose causes of preventable blindness in adults, and has opened an opioid addiction treatment centre in Ohio.

Entrepreneurship

Beyond Meat

The company markets its products, such as imitation burgers, to omnivores. They are available at restaurants and grocery stores in the US, Canada, Europe and Asia. It aims to start production in Asia in 2020, with an eye to selling its products in China.

Ecotricity

Britain’s largest green energy company supplies more than 200,000 customers from a growing fleet of wind turbines. It also operates a network of electric vehicle charging points.

EG Group

The UK-based petrol station and convenience store operator bought US supermarket group Kroger’s convenience store business for $2.2bn, giving it 800 stores in North America. A listing on a US exchange to raise funds for expansion is being considered.

Richer Sounds

The owner of the UK hi-fi and television retailer, Julian Richer, sold his business to his staff last year. Richer refuses to employ people on zero-hours contracts and donates 15 per cent of operating profit to charity. Staff turnover is less than half the average for UK retailers, according to the company.

Rocket Lab

The aerospace company specialises in the launch of small satellites. It was funded initially by government grants. Rocket Lab has reached a $1bn-plus valuation after raising $140m in 2018 to fund increased production of its Electron rockets.

Developing Markets

Bioceres Crop Solutions

The Argentine agricultural biotechnology company develops and sells genetically modified soybean, wheat and alfalfa seeds, as well as crop nutrition products. Its drought-resistant soybean has won regulatory approval in the US and it is awaiting a approval in China.

Farmer’s Cheese Making

Cheese, long considered a luxury good in Pakistan, is increasingly popular. Founder Imran Saleh started with a market stall in Lahore and now sells his products at 40 supermarkets.

Koko Networks

The company supplies clean cooking fuel in the form of bioethanol to homes in Nairobi and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. Customers buy a cooker manufactured by Koko, pre-pay for fuel via mobile app, and refill their canisters at vending points.

Lenskart

Unlike other retailers in India’s fragmented eyewear market, Lenskart controls its own manufacturing. India’s market for vision correction is an estimated $2bn. Indian private equity firm Kedaara Capital has invested $55m in Lenskart.

Twiga

The app-enabled logistics company connects farmers and vendors in Kenya. The platform aggregates orders and cuts out intermediaries. It promises to improve the price farmers receive for crops such as potatoes, bananas and onions, while simultaneously providing urban vendors with a reliable supply of fresh vegetables at a discount.

Smaller Company

Adaptive Biotechnologies

The company has created a platform to make a map of the immune system accessible to researchers and clinicians. It markets two products: immunoSEQ, which sequences immune cell receptors, and clonoSEQ, which measures blood cancer cells that survive therapy in blood marrow.

CMR Surgical

The UK medical robotics company is already a unicorn. Its Versius robots help surgeons carry out keyhole operations and are being launched in Europe and Asia.

Reformation

The women’s fast-fashion US retailer has an agile, Zara-like production model that produces 15-20 new styles a week. Most items go from sketch to store in less than four weeks, rather than the six months of a conventional fashion cycle. It uses eco-friendly textiles, including recycled cashmere and nylon.

Solar Foods

The Finnish start-up is developing a protein ingredient that can be made using minimal energy — a resource-light alternative to animal and plant-based protein. In 2018, the company was selected for the European Space Agency’s incubator scheme to develop food production techniques in space. It is currently making 1kg of protein per day in pilot production and aims to start commercialising it in 2021.

Timpson

The UK retailer specialises in shoe repairs, key cutting and other domestic services. Chief executive James Timpson has overseen a rapid expansion of the business, which now has 2,000 stores. It has planning permission for a Timpson university in Manchester where it aims to offer degree-level training to 500 staff a year, including ex-offenders.

Judges

- Lionel Barber

Former Financial Times editor and chair of the judging panel - Lakshmi Mittal

Chairman and chief executive of ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steelmaker - Anne Méaux

Founder and president of Image Sept, a Paris-based public affairs and media relations company - Robert Armstrong

Financial Times US finance editor and former head of the Lex column - Brooke Masters

Financial Times comment and analysis editor and former companies editor - Edward Bonham Carter

Vice-chairman of Jupiter Fund Management - Leo Johnson

PwC disruption lead and co-presenter of BBC Radio 4 series ‘FutureProofing’ - Brent Hoberman

Chairman and co-founder of Founders Factory, a corporate backed incubator/accelerator - Peter Tufano

Professor of finance and Peter Moores dean, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Comments