Byju’s finds profitability in Indian consumers’ hunger for education

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This article is part of the FT/ArcelorMittal Boldness in Business awards, recognising companies and individuals with novel answers to everyday needs.

In an improvised sound stage in Bangalore, India, actress Tarana Thakurdas stands under studio lights in front of a green screen as a cameraman frames a shot. A man with a clapperboard leaps in front of the camera. “Greater Than, Less Than: scene two, take one,” he declares with a snap of the board. Then comes the call from the director: “Action!”

Thakurdas, who has worked as a school drama teacher and commercial actress, launches into an energetic monologue. Her subject: a school sports day, two rival teams who have earned 1,028 and 666 points respectively, and how children can understand which team won by figuring out which number is greater than the other. Dressed in a polo shirt and baseball cap, she points to imaginary scoreboards and an imaginary number line as she cheerfully starts the lesson.

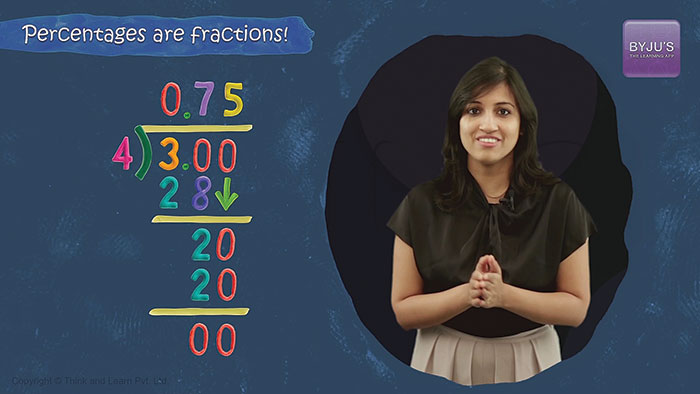

After the filming, the footage will be enhanced with animations of children playing sports in front of a stadium crowd, scoreboards and a number line. The aim is to create an engaging and lucid explanation of a basic maths concept for year-four students (who are about nine years old). For her next role, Thakurdas will swap her baseball cap for gardening gear to give a lesson on the life cycle of plants, using real potted plants, watering cans and shovels as props.

Such elaborate, carefully crafted short educational films — on topics ranging from basic maths concepts to advanced trigonometry, chemistry and physics — are at the heart of Byju’s, the fast-growing Indian educational technology company that has built a profitable business by catering to Indians’ hunger for high-quality education.

Started in 2011, the company — whose founder Byju Raveendran was a star maths tutor — today has 3m subscribers: students who pay $170 a year to access maths and science tutorials, and game-based practice tests, to help them master the academic curriculum for years four to 12. The company operates on a “freemium” model, where students can download the app and access some limited content on their phone for a brief period before they need to subscribe to gain full access.

To fund its transition from an offline one-man tutoring business to a big online educational company, Byju’s has raised $1.2bn from high-profile global investors, including California-based venture capital firm Sequoia Capital, Chinese technology group Tencent, South African ecommerce company Naspers, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, and the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative (set up by Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan).

Following its most recent funding round, Byju’s was valued at $8bn, making it the most valuable educational technology company in the world. Yet what distinguishes the Bangalore-based business from many other glittering Indian tech start-ups is that it has found a path to profitability. That is thanks to the enduring nature of its academic content, all created in house by diverse teams, including subject specialists, graphic artists, animators and writers, who together brainstorm how best to teach complicated topics.

One recent afternoon, for example, engineers and a former maths teacher with a masters in applied maths sat down to discuss how to illustrate complicated concepts of trigonometry to make them understandable to high school students, trying out various illustrations on a computer. “We spent a lot of time creating the content correctly and, once it’s done, we don’t need to change it very often,” says Anita Kishore, Byju’s chief strategy officer. “That is what makes it possible to generate a profit.

“For an entertainment company like, say, Netflix, you need to keep churning out new content. But maths or science is not changing fundamentally each year. Once we [have a format to] teach Pythagoras’ theorem, it’s not like you will have to change it.”

For the financial year ending March 31 2019, Byju’s made a profit of $2.8m on revenues of $210m. This year, revenues are set to come in at about $422m. By 2024, Raveendran estimates Byju’s will have between 14m and 15m subscribers, generating at least $3bn in revenues, with profits of $1bn-$1.2bn.

“There is a large percentage of the population that is very aspirational and hungry to learn,” says Raveendran. “People know education is the only way to make it big. They all understand the importance of learning. We don’t need to create awareness of that — it is already there.”

From big cities to small towns, most Indians indeed see education as the key to economic progress and a better life. But the quality of education available to the country’s estimated 267m school-age children varies tremendously, depending on their location and family income. Most government schools suffer from a high ratio of students to teachers, weak teaching quality and poor teacher attendance. Private schools are mushrooming but are often little better than their state counterparts.

In recent years, various Indian and international companies have tried to promote tech-based answers to help such schools improve quality and teach more effectively. But they have foundered because of the difficulties of dealing with educational bureaucracies in both the public and private sectors. Byju’s, by contrast, has found success by selling services directly to parents and students — a far easier proposition. The company’s engaging videos and tests — which are delivered exclusively by app — are promoted as a supplement to classroom teaching, and a useful tool that allows children to study and practise when they choose.

“Right from the beginning, Raveendran understood the power of B2C [business to consumer],” says TV Mohandas Pai, a partner at Bangalore-based Aarin Capital, the company’s first outside investor, and a former director at Indian IT giant Infosys. “He knew the formula was to meet parents and students, and wow them with technology and direct communication.

“When they see how Byju’s teaches, the children get excited. Parents get excited because they feel it will give their children a competitive edge.”

The son of two small-town schoolteachers from southern India, Raveendran began his foray into the education business as an offline, flesh-and-blood maths coach, helping college students prepare for the ultra-competitive entrance exams for business school. As his reputation grew, he travelled constantly, lecturing in ever larger venues, from 500-seat auditoriums to a 24,000-seat sports stadium.

Later, Raveendran, an engineer by training, turned to technology to expand his reach. He set up satellite networks that allowed him to transmit his lectures live and reach tens of thousands of students in multiple locations across India. Eventually, Raveendran and his team realised they could improve their service by stopping live lectures in favour of pre-recorded presentations, enhanced with extra graphics and made accessible to students at any time and place. “We realised that live was not really necessary,” says Kishore.

When the Byju’s app launched in 2015 it already had an extensive video library, featuring engaging presenters and sometimes Raveendran himself. Kishore says about 85 per cent of subscribers renew each year, and the average user is active for 71 minutes a day. Just a quarter of subscribers are in India’s six biggest cities; while nearly 30 per cent live outside India’s 100 biggest cities. Many access the content on smartphones that cost less than $150. “We are democratising education,” says Kishore.

The company sees plenty of scope to expand in India. At present, all its content is in English, but it hopes to make its maths and science curriculum available soon in an array of Indian languages, increasing accessibility for those who do not attend English-medium schools.

Byju’s is also looking to go beyond maths and science to offer online courses in parallel with the Indian education system’s social science curriculum, and courses in English for those struggling to master the language. The company may also offer some human tutoring for subscribers who need extra, face-to-face help.

But Raveendran is looking at opportunities further afield, too. So far, Byju’s has spent only about $300m of its $1.2bn primary capital, leaving it with a significant war chest to fund forays into foreign markets, where it hopes to replicate its successful Indian formula. Small pilot projects have already begun in a couple of other English-speaking markets, though Raveendran declines to identify where, saying only that the company will have to develop content appropriate to those markets.

“The business in India doesn’t require cash, but there is an opportunity to do this in multiple markets,” he says. “What we need to figure out is the willingness to pay for education elsewhere. Here, parental involvement in kids’ education is very strong. Is there such a big need elsewhere the way we have it in India? These are the questions we have to find answers for.”

Comments