Theaster Gates at Kunstmuseum Basel — an opulent web of words and imagery

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Even today, when many artists multitask as skilfully as the busiest working mother, Theaster Gates is a master juggler. Sculpture, architecture, film and song are just some of the arteries running through his remarkably rich practice.

The new exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel acts as a magnificent showcase for the Chicago-born, African-American artist’s breadth. Embracing performance, singing, photography, sculpture, installation, print, publishing, film and archive, it unfolds over both of the museum’s spaces — Nebau in the centre of town, Gegenwart on the riverside — in a topography that maps Gates’s borderless horizons.

To feel the pulse of this fiesta, it makes sense to start with the most condensed display, which is hosted by a single gallery at the Kunstmuseum’s central venue. Here Gates chooses to open with a 15th-century painting drawn from the museum’s own collection. Entitled “Virgin with Child in front of a Landscape” (1530) by the Dutch master Maerten van Heemskerck, it undermines classical convention by depicting Mary with a sly, sideways, secret-hugging smile rather than the customary demure moue.

Renaming her “Ghetto Madonna”, Gates declares himself in sympathy with this Mary’s resistance to traditional representation. Indeed, his entire show can be read as a passionate denunciation of centuries-old efforts to cage women, particularly black women, into stereotypes. Yet so opulent is Gates’s web of image, word and song that it creates its own paradox: for this is clearly an artist who loves to represent his world even as he knows the dangers of such authoritarian activity.

At the kernel resides Gates’s concept of the Black Madonna, a figure that fuses myths around the Virgin Mary with those of black women in history and today. As Gates puts it in an interview about the show with Kunstmuseum curator Søren Grammel, “The everyday black woman is an under-celebrated figure. The Madonna represents female firefighters, female news anchors, female weather people, female bus drivers, female social workers.”

Yet there was a “real” Madonna in Gates’ own history. The gift of a simple keychain of Mary and Child — which he describes as like a “rabbit’s foot” lucky charm — became for him “in all her brokenness . . . the ideal Mary: the Mary of the keys, the Mary of my pocket, the Mary of my purse. You may forget about her but she’s always there.”

That touching memory resolves here into “Black Madonna” (2018), a sculpture of the Virgin and Child whose rigid, queenly, near-medieval iteration is complicated by the work’s material: obsidian-black tar. Gates, who has long worked with this substance, likes the way that the tar puts his sculptures at risk from melting. His Mary’s body is, as he puts it, “constantly affected by the world”.

Alone in the sunken lobby of the Kunstmuseum’s Gegenwart space, “Black Madonna” certainly looks vulnerable. It was profoundly moving to watch Gates’s performance — in front of a packed audience — in the opening week, when he drew close and sang to her as if there was no one else in the room.

She also has other more permanent companions. Running around the wall in a single glittering row is “Walking Prayer” (2018), an installation of 2,500 books about black and African-American experience which Gates has rebound in black and retitled in gilt with his own lyrical phrases — No, Mama, Salvation is Dark, And What is Mother — in the hope that new readers might be provoked into looking within.

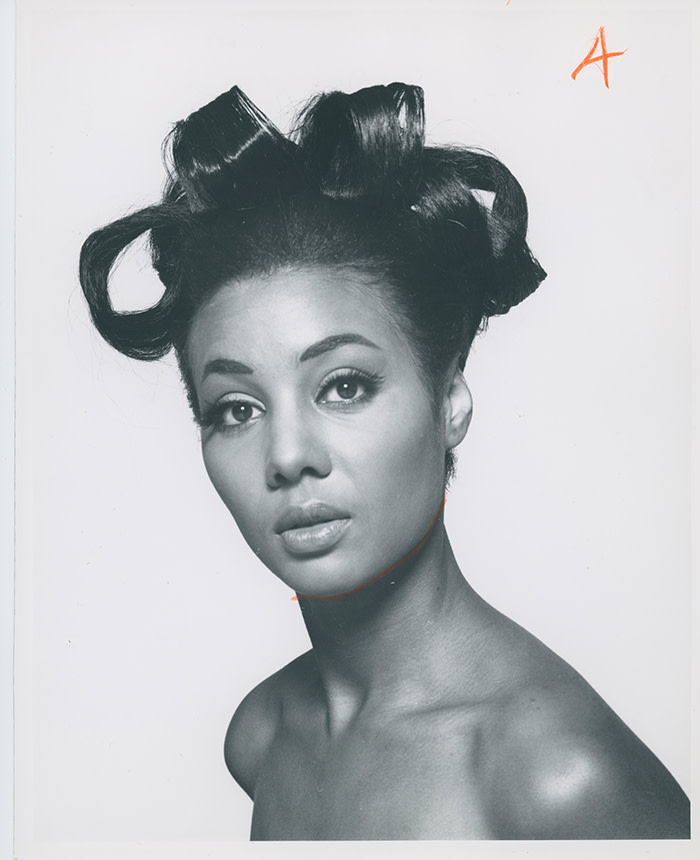

Printing carries huge significance for Gates. Some of the books in “Walking Prayer” were originally published by Johnson Publishing, the seminal publishing company responsible for magazines such as Ebony and Jet, which Gates describes as “an early platform for self-healing” for black American people. The company also provides the images for his stunning installation — in the Nebau space — “Facsimile Cabinet of Women Origin Stories” (2018), which brings together over 2,500 pictures drawn from their magazines. These 20th-century depictions of black female glamour — in swimsuits, bridal gowns, evening dresses — are stored in a vast cabinet inspired by that used by the museum to house its illustrious collection of historical prints and drawings.

Gates’s fascination with archives, so often used to reinforce abusive systems of power, emerged, he says, as he realised that “people who organised information [ . . . ] were involved in a work that was not just about the present but about the future.”

As well as organising information, Gates also produces it. His Black Madonna Press has already published several books and an album cover. In Basel, whose history as a hub of humanist thought makes it, as Gates points out, “hard not to think about the history of printing”, he has borrowed a vintage Heidelberg press from the nearby Swiss Museum for Paper, Writing and Printing.

Installed in a niche on the ground floor, where it can also be viewed from the mezzanine balcony above, the handsome wooden contraption will be in use regularly during the exhibition. I watched as two operators meticulously fed sheets of thick, creamy paper into the press’s old-fashioned jaws and took home one of the results: a square-format poem by Gates in a velvety-black font whose elliptical fragments included: “It’s a militant south/But there is a fountain/behind those chains”.

We live at a moment when imagery — from Hollywood to contemporary art — is notably powerful and controversial. Gates’s unwavering commitment to highlight the mechanisms behind the myths is embodied by the plethora of printers’ marks on the magazine photographs of black women that run like a seam throughout this exhibition. His skill at reminding us that reality is sacrificed at every stage of the process, while stoking our hunger for visual fantasy, makes him one of the most important contemporary artists today.

To October 21, kunstmuseumbasel.ch

Comments