Bacon-Giacometti at the Fondation Beyeler: a pairing of modernist giants

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

How to astonish the world’s most sophisticated art audience? Bacon-Giacometti, the Fondation Beyeler’s show during this year’s Art Basel fair, risks the familiar and transforms it into the sublime. Europe’s greatest postwar painter and greatest postwar sculptor have each been massively exposed lately; their dialogue with each other, and with this iconic gallery’s towering day-lit spaces, jolts us into a fresh experience of all three.

Bacon’s brutal swagger portrait “Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho”, a ferocious black-robed harridan before flashy motorists and spinning tyres, glares at Giacometti’s “Femme au Chariot”, a sculpture on wheels also based on a view of Isabel from afar: a moment of perfect visual affinity backed by biographical context — Isabel was both men’s lover (and Bacon’s only female partner). A series of portraits in paint, pencil, bronze and terracotta spanning 1936-67 unravels how her strong features, prominent chin and high cheekbones offered the resistance which allowed each artist to savage her into an image at once monstrous and full of pathos.

Pity, horror, awe and supreme formal virtuosity: Bacon and Giacometti both had false start careers before World War II and emerged after it with a conviction, against the tide of abstraction, that only an art of Old Master gravitas, obsessively concerned with distortions and fragments of the human form, could uphold figuration after the Holocaust. Bacon’s sinister “Marching Figures”, an army of white silhouettes within a ghostly outline of a cage topped by a ghastly dictator’s bust, shimmer here against Giacometti’s huddle of massed figures, “La Forêt”. The desperate woman on a swing in Bacon’s “Study for the Nurse in the Film Battleship Potemkin” veers towards Giacometti’s filigree suspended figure, stretched out to suggest a crucifixion, in the delicate plaster frame “La Cage”.

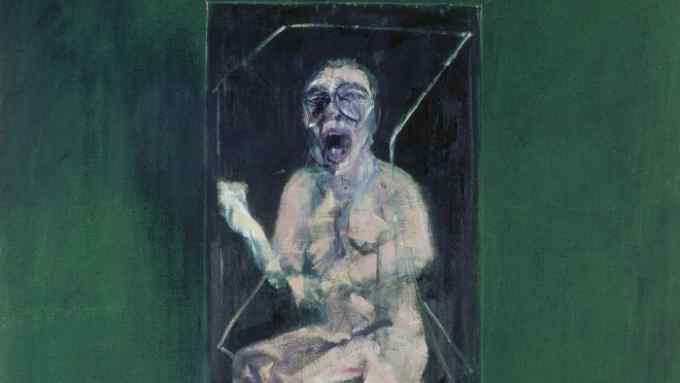

The similarities, and the shared existentialist milieu, of these two deeply pessimistic artists are pronounced, but so are compelling contrasts, the drama of what makes each unique. In a gallery entitled “La Vérité Crainte”, two Bacon screaming popes imprisoned on their thrones, the privately owned “Study after Velázquez” and MoMA’s theatrical gold-encased “Study for Portrait VII”, face Giacometti’s hieratic, still, seated figures: the fragile, plaster “Homme à mi-corps” and the bronze “Eli Lotar III (assis)”, both with arms and huge hands so elongated that they seem to imprison their owners’ bodies. Hysterical versus mute anguish; voluptuous, violent colour versus bleached out, deathly pallor: difference within likeness of such high wire expressiveness makes each more affecting.

For from the initial salvo, Bacon’s early yelling “Head VI” and Giacometti’s “Le Nez” — a skull hung from a crossbar like a gallows, with extravagantly protruding nose suggesting a gun — both 1949, it is clear that Bacon brings out the subliminal menace in Giacometti, while Giacometti makes us aware of the monumental, sculptural ambition of Bacon’s painting from the start. “This is the man who has influenced me more than anyone”, Bacon said of the sculptor.

Although Giacometti drew then sculpted from life whereas Bacon, fearing preliminary drawing would detract from the spontaneity of the first fluid, loaded brush marks, fused mostly photographic sources, films here show close parallels in their ways of working: obsessive stalking of the motif, filthy chaotic hovels as studios, places which shape a sense projected by each of dark, claustrophobic interiors.

This aspect is flamboyantly offset by the lavish, light-filled Beyeler, its glassy façades giving on to broad vistas of cornfields, vineyards, ancient trees. The incongruity is sharp: the apogee of art world wealth and grace — Beyeler, a successful, influential, sympathetic dealer, was founder of Art Basel — versus the tough grit of the lone artist in his atelier confronting his demons. But then, Renzo Piano’s Fondation is among the brightest, most optimistic 20th-century galleries anywhere — “I have always perceived works of art as parables of creation, as an expression of joie de vivre,” Beyeler declared at the opening — and the demons, if aestheticised, roam thrillingly here as things of unlikely beauty and eloquence.

Go for the central gallery alone, amply accommodating three triptychs, five further huge Bacon canvases, and arenas of nearly a dozen large Giacometti figures. Crowds circle among the stately, enigmatic, upthrusting “Femmes de Venise”, take selfies, imitating the poses of various versions of “L’Homme qui marche”, and stand dwarfed by the10-foot “Grande Femme IV”.

The performative element in turn energises Bacon’s key paintings of movement gathered here, from the Beyeler’s own unruly, white on maroon, almost affectionate “Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle” — Bacon’s clumsy, vulnerable lover peering out suspiciously beneath a helmet — to the staging of birth, copulation and death as butchery and voyeurism in the Hirshhorn’s lime/midnight blue “Triptych” inspired by TS Eliot’s “Sweeney Agonistes”. Not since Tate and MoMA’s Matisse Picasso in 2002 has a pairing of modernist giants felt so apt and pleasurable.

To September 2, fondationbeyeler.ch

Comments