Navigating work as a blind person

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

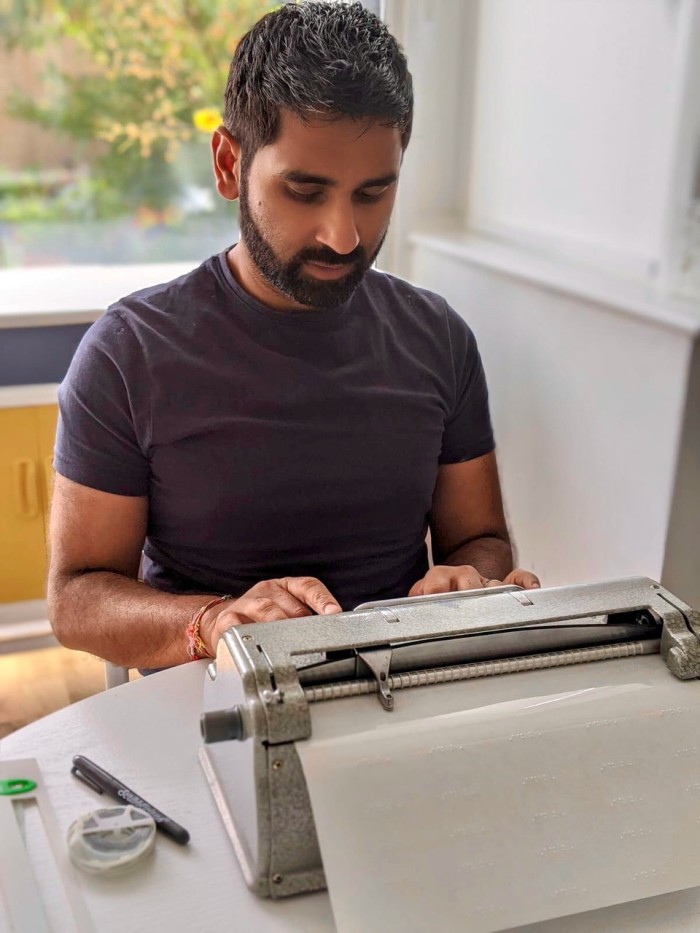

Amit Patel graduated from Cambridge university and qualified as an accident and emergency doctor. But his training did not prepare him for what happened next.

During his studies, he was diagnosed with keratoconus — a condition that affects the shape of the front of the eye, but is treatable with corneal transplant surgery. Patel was one of the rare people where the transplanted tissue was rejected, however, and he became blind overnight after a haemorrhage behind the eyes.

“I had to relearn how to live with sight loss; simple things like how to make a cup of tea became a journey of planning,” Patel says. “I was terrified of stepping outside and didn’t leave my house for three months. I needed a reason to wake up, I needed to be back in society — I knew I could do this and a big part of that was work.”

He is one of 340,000 people in the UK who are blind or partially sighted. But a 2019 study by charity the Royal National Institute of Blind People found that the employment rate for those who are blind or partially sighted was 27 per cent, compared with 51 per cent among people with other disabilities and 76 per cent for the general population.

The study also found that there had been no significant change in employment rates for blind people compared with a similar study in 1991.

Research carried out in Northern Ireland by the RNIB and Birmingham university found the biggest barriers to employment for people with sight loss were misconceptions of their ability, inaccessible recruitment practices, and insufficient workplace support.

For Patel, crucial support came from his “amazing” wife Seema, with whom he has two children. She used to joke that he could not have dinner until he did his Braille exercises. A guide dog, Kika, helped him navigate rush hour on London public transport and was fitted with a video camera to record discrimination that Patel could not see, such as station staff deliberately ignoring him. He learned how to use a screen reader to navigate documents and the internet and eventually started looking for administrative jobs.

“Getting access to a job vacancy is the first hurdle a person with sight loss faces,” says Martin O’Kane, Strategic Lead for Employment and Technology at RNIB. “Often websites are not accessible — poorly structured without screen readers or magnification software.”

RNIB advises employers who are unable to adapt their own websites to use those recruiting websites that do meet the sight loss accessibility test, such as Evenbreak.

For Patel, however, it was only when he “excluded his disability from applications” that he was called for interviews. “I remember the first interview I was called for,” he says. “They didn’t know what to make of me when I asked if they could describe the room to me before we began. I didn’t get the job because, in their words, I hadn’t told them I was blind in the application and that I wouldn’t be a good fit for them.”

O’Kane says that “not understanding the capacity level of a person with sight loss by employers is a barrier, but making simple adjustments can assist a person with sight loss to access and retain a job”. The RNIB estimates that 11,000 people with sight loss are currently looking for work.

The UK government’s Access to Work scheme is aimed at helping people to find and keep a job if they have a disability, funding travel and equipment costs as well as a job coach to support people to transition smoothly into the workplace.

But Patel argues that “even with government support, the onus is on employers, because the biggest barrier people with sight loss face is the assumption we cannot do the things in the job advert because we cannot see. These negative attitudes need to change to embrace a willingness to accommodate our needs with simple things like a specialist screen readers and keyboards.”

Embracing his sight loss, Patel became self-employed as an inclusion and diversity consultant and a motivational speaker, wrote a book called “Kika and Me”, and now works on the TV programme Dog Squad on the CBBC channel.

He plans to build an outdoor timber kitchen this year, with his two children, aged three and seven, and Kika. “With three pairs of eyes helping me, I’m pretty sure the timber will level up,” he laughs.

“When I faced barriers trying to get a job, it used to rattle around in my mind. Now, I look for challenges to make those changes — the workplace becomes more confident when it empowers a workforce with practical knowledge to assist blind people.”

Click here to read more about accessibility features on FT.com

Comments