At home with the Aesop aesthete

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A thick air of calm hangs in the spaces that Suzanne Santos curates. The Aesop co-founder’s Melbourne home, a 19th-century Victorian in the suburb of North Caulfield, is serene by design, with smooth, variegated marble floors that stretch the length of the house, reflecting the bright, pale walls, light wood panelling and sweeping ivory curtains. The bathroom, an uncluttered sliver in the middle of the house, has marble floors that creep up the walls and sink. It could well be an Aesop store, with the brand’s signature black-and-white labelled products scattered intentionally throughout.

“It provides me with tangible peace,” says Santos. A keen thrifter, she has filled her home with midcentury furniture and charity-shop finds, including vases, sets of china and a painting by the Australian artist John Brack. “It’s an environment that lends itself to comfort, and the ability to express my values, like cooking, listening to the radio or reading. I’ve set aside a place for that.”

Santos’ zen sensibility helped shape the look and feel of Aesop, the Australian skincare brand that has become a global phenomenon and signifier of quiet sophistication. Each of the brand’s stores and counters, of which there are more than 400 around the world, is unique in design yet distinctly Aesop, while the products engender a fervent loyalty among its clients. L’Oréal purchased Aesop from Brazilian conglomerate Natura for $2.5bn last year, in a record deal that makes it the French beauty company’s highest-value acquisition to date.

But its story starts with Dennis Paphitis, who once owned a hair salon called Emeis in Armadale, in south‑east Melbourne. He started blending essential oils into hair-colouring products to mask the unpleasant smell of ammonia and other chemicals in the salon, before expanding into skincare. A cease-and-desist letter from a toiletries company that sounded phonetically similar forced Paphitis to rebrand his salon and products in 1989; in its place, he launched Aesop. The brand was named after the Greek storyteller as a commentary on the often inflated skincare claims made by the beauty industry. Santos, who started working with Paphitis in 1987, was his first employee, and together they created the blueprint for the brand.

“I don’t believe that many people actually understand our legacy in changing the course of cosmetics,” says Santos. She has worn a number of hats within Aesop over the past 37 years, and is now chief customer officer and spokesperson; Paphitis resigned from the board in 2019 after selling his remaining stake in the business in 2016. “It was the circumstances of an exhilarating era,” she says, of how the brand came up in the midst of a social shift in diets and health, and “people’s perception of what’s good or bad”. She continues: “It wasn’t as if the cosmetics industry owned this mass social change, but it certainly, given its influence, played a part in that recreation of people’s perceptions around quality and values.”

Aesop was a disruptor long before the term became a business buzzword. The products were designed to be without the “filler” commonly found in beauty formulations, instead using potent and functional ingredients that purported to be more beneficial. Aesop removed “the unnecessary elements that helped to create extraordinary margins but did nothing for the worth of the individual who bought them”, says Santos. “Our original products – the body washes and the hand balms – were intentional, purely based on purpose: which ingredients, inclusive of essential oils, were going to provide effective and sustained hydration for the skin. That’s the purity of context.”

The brand has always eschewed traditional beauty marketing – such as print media advertising and paid ambassadors – instead orchestrating in-store installations and seasonal displays. One stunt saw a Melbourne store filled thigh-deep with crunchy autumn leaves collected from the city. Another transformed stores in Sydney and Melbourne into “queer libraries”, with books by LGBTQIA+ authors replacing the products that normally line the shelves. In both cases, Aesop sold more products than they would typically over the same periods. “Dennis was part of that first generation who led, certainly in cosmetics, an association with the arts – whether design, architecture, literature, film – as an alternative to marketing,” says Santos.

For Santos, what’s in the soap matters. But what matters more is what the soap represents. Aesop has distilled the essence of good taste. To have a bottle of Resurrection Aromatique Hand Wash next to your bathroom sink telegraphs that you, too, have garnered a kind of cultural cachet; it’s found in modernist restaurants, boutique hotels and in the bathroom of Succession’s Shiv Roy. Stories abound of people refilling their Aesop bottles with cheaper soap alternatives; you can even buy empty ones off eBay.

What’s not so easy to replicate – although many have tried – is Aesop’s distinct fragrance, which is hearty and sophisticated, sitting somewhere between woody, citrusy and herbaceous. The scent wafts out of Aesop’s stores around the world. “We often say you will smell an Aesop store before you see one,” says the brand’s director of global retail design Marianne Lardilleux. Perfume has also become a big part of Aesop’s business, growing 50 per cent in 2022, with 10 different scents (from £110) now in its roster and some of the more recent ones designed by nose Barnabé Fillion, who has created scents for Paul Smith and Le Labo.

What Aesop has done particularly well is align the brand so that it sits in the luxury category, but with a slightly more accessible price point (the hand wash is £31 for 500ml) than its competitors such as Byredo (£44 for 450ml) or Le Labo (£38 for 500ml). According to Bain & Company, it’s also a leader in the fast-growth luxury bath and body market, where it represents a more accessible pathway to the experiences of spas. “Beauty has become a crowded category over the past five years,” says Vandana Radhakrishnan, a partner at Bain. “The value of brands like Aesop and other fast-growth insurgent beauty brands is that they have created highly experiential digital and physical spaces with compelling content that tells a product and brand story in a very differentiated way.”

The company won’t reveal how many units it sells per product, but its heavy hitters are the aforementioned hand wash, Resurrection Aromatique Hand Balm, Lucent Facial Concentrate, Exalted Eye Serum and – of course – the Post-Poo Drops, a cult, slightly cheeky product that was first conceived in a collaboration with APC in 2012.

Cult-like is a term often associated with Aesop, not just for its products but also in its approach to customer service – what the brand likes to call “hosting”. A recent TikTok video poked fun at one staff interaction, in which an overbearing Aesop store clerk took the user on a “journey” to discover its deodorant, beginning with hand-washing (a store signature) and ending with her being admonished for damaging the fragrance’s base note. This training in “formal etiquette” is addressed in Aesop’s Rizzoli book in a chapter called Xenophilia: “It is a truth universally (if internally) acknowledged that new Aesop employees are faced with complex, often irrational codes and expectations. They need a guide to help demystify and absorb these – and, in turn, to help them assimilate and reach their professional potential.”

Santos adds: “How our retail staff interface with our customers is about – and what we seem to be stripping out of our fingers every moment of the day – humanity, and a human approach to an encounter that matters. The exchange of money and goods matters to people – people work hard for that – and that encounter, and the way that we facilitate it, has very few peers.”

Want to read HTSI before everyone else? Get all the top stories straight to your inbox every Friday. Sign up to our free weekly newsletter here

Certainly, the gracious manner of Aesop’s staff is consistent throughout the company, from in-store to its head office in Collingwood, to the north-east of Melbourne. The offices – again – have a serene, cosy-industrial feel, with floor-to-ceiling windows, tidy lockers for staff to put their belongings in and midcentury and antique furniture. Calming music, like a kind of meditative sound bath, plays throughout and – of course – the entire place smells on-brand. The staff drink from white porcelain cups with quotes circling around the inside, including “dare to err and to dream”, by Friedrich Schiller, and “anyone who keeps the ability to see beauty never grows old”, by Franz Kafka. The quotes, too, line the walls.

“Nothing about ourselves is contrived,” insists Santos. “I used to describe the brand as being a metaphor for Dennis. All the layers, inclusive of the philosophy. But there’s never been a doctrine. Others love to write doctrines about us. It’s like sediment, it’s just layers of life built into behaviours that became part of what is now.”

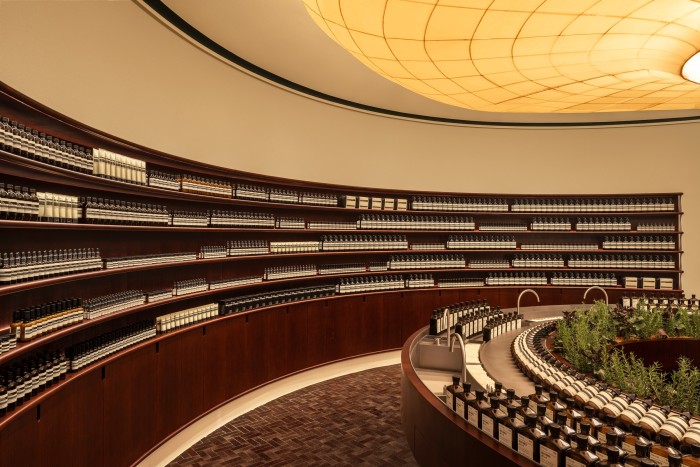

Much of Aesop’s global revere is in the physical design of the stores, which are masterminded by an impressive roster of names, who often have a connection to each location’s geography. Typically, new stores have been positioned in trendy, slightly out-of-the-way neighbourhoods, such as on Broadway Market in Hackney, but a new strategy has put Aesop’s latest openings in more commercial locations, on Regent Street and in the Marais in Paris – two central tourist thoroughfares. A push into new markets – including the opening of a 300sq m store in Shanghai – has seen a boom in growth: Aesop’s sales in 2022 were up 21 per cent from the previous year, to A$766mn (about £403mn). How Aesop navigates further expansion, while remaining authentic to its original principles, will be a challenge. Being owned by one of the biggest beauty conglomerates in the world isn’t conducive to a brand that has traded in being an outsider to the industry for the past 37 years. How does Aesop maintain its values in the face of this?

“It’s not a struggle,” says Santos. “The tangible practices of what we choose, both at an ingredient level, to create that formula, and at a packaging level, are done in an unrelenting way to the very best of our ability. That hasn’t changed. Scale has not changed that.”

To say that Santos is principled, and exacting, is an understatement. She seems to give a lot of consideration to what she does – be it her business interests, the way she is perceived, and the way she chooses to live. Everything in her home is thought out, from the design of her couch (by Australian brand Jardan) to the sail-shaped light shade hanging over it (by French designer Paris Au Mois D’Août). But “there’s not been an excessive or waste of thought”, she says. “The house is more designed as something that would live long – I really mean this – long beyond me, that wouldn’t one day be immediately desecrated by someone who might buy it.”

As we’re finishing up our interview, and the table is cleared of its breakfast contents, she hands me a parting gift, a book: Do Design: Why Beauty Is Key to Everything by Alan Moore. It implores the reader to rethink not only what we produce, but how and why. “I think you’ll like this,” she says, “and when you’re done reading it, you can pass it on to someone else.” Santos’s mission – and indeed Aesop’s – has been clear from the start: to spread the word of beautiful, calm design.

Comments