Beauty, by holy order

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The first prayers of the day are said at 5 o’clock in the morning at the Abbazia di Praglia, at the foot of the hills outside Padua, Italy. The monks make their way through the 15th-century cloister to the church, with its barrel-vaulted ceilings and frescoes by Campagnola, where, as sunrise breaks through the windows, they say their matins. Afterwards, they follow the daily routine as set out by Saint Benedict in 530AD, to “labour at whatever is necessary until about the fourth hour, and from the fourth hour until about the sixth let them apply themselves to reading”. At Praglia, this labour might be any pursuit that enables the smooth running of the abbey: cleaning, cooking, vegetable-growing, teaching in local parishes or tending the bee hives. Ora et labora is the monks’ dictum: prayer and work. Idleness, counselled Benedict, “is the enemy of the soul”.

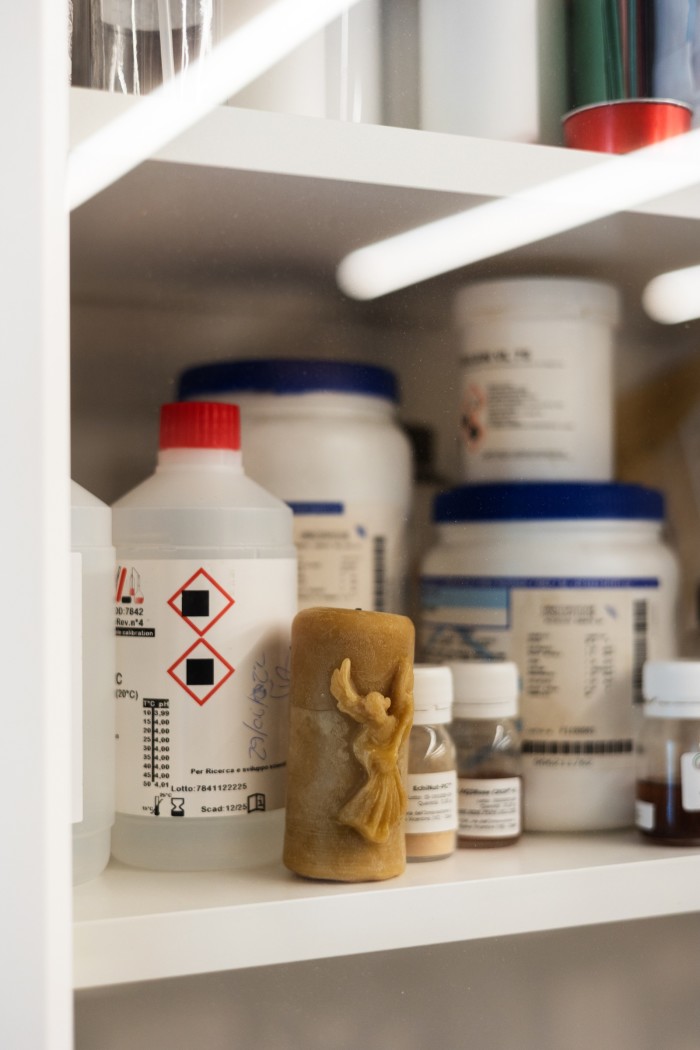

In a laboratory at the heart of the abbey, a small group of monks takes a more chemically minded approach. One monk, two in training and a herbal technician spend their days measuring out quantities of oil and water, adding dashes of rose water, calendula and sage oil or drizzles of honey, and beating them into tonics, creams and tinctures that are shipped around the world. Their names have a modern cadence – toners, moisturisers and aftershaves – but they are continuing work that Benedictines have practised for centuries.

The abbey has run a herb garden since the 16th century. The monastery was closed down twice – first by Napoleon in 1810 and then by royal dynasty the House of Savoy in 1867 – but resumed its function in 1904, and began making cosmetics in the 1970s, when beehives were introduced. The 20 products today include a cream containing propolis, the resin-like substance bees use to build hives (€16.50); cocoa-butter lip balm enriched with beeswax, honey and propolis extract (€3); soothing calendula creams (€18.50); and olive soap made using a traditional cold-kneading process (€4). Starting at 9am, the monks weigh out their ingredients and begin mixing, heating, cooling, potting, bottling, labelling and shipping.

Benedictine abbeys such as di Praglia have long prided themselves on their ability to sustain themselves without support from the Catholic church. Creating cosmetics – which in di Praglia’s case sits alongside book restoration, wine making and a conference centre in the monastery’s roster of small businesses – is important for the survival of a way of life. “They were self-sufficient right from their birth,” says Matteo Zampieri, the tecnico erborista, or herbal technician, who oversees the running of the laboratory at the abbey, “small worlds that had to live from their own work and their own revenues”.

Many holy orders restarted the ancient practice of herbalism in the 20th century in order to make use of their skills and land when faced with rising energy costs. In France, for instance, a group of nuns in Chantelle began making their own products in 1954, led by a nun who had been a chemist before she took her vows. A few years ago, the Cistercian Monastery of Nuestra Señora de Vico in Spain’s Rioja region added lime blossom, thyme, mint and olive oil-based moisturising creams to its long-standing line of fresh pasta and biscuits (“Hallelujahs without sugar”).

“It is important to work and to have income,” says Father Avakum from the forest-covered hills of Mount Athos in Greece, a religious community comprising 20 monasteries. “For some of the monks who live alone, this is their only income.” Mount Athos is famed for prohibiting women from within 500m of its coast, a convention that allows the orthodox monks to devote their attention to the Virgin Mary. They make incense, and ointments including Black Walnut Tincture (€16) to aid digestion, SPF50 made with hyaluronic acid and lavender flower water (€12) and calming face cream with kombucha, oregano and rose (€13). The money is used mostly “to preserve this place as is”, says Father Avakum, and “for the everyday needs of the people that come to visit Mount Athos and of the monks”.

But creating products remains foremost a meditative act of devotion in the eyes of Father John, who runs Sanctuary Products from St Augustine’s Abbey, a Victorian friary in Surrey. “There is very, very much a spiritual element,” he emphasises. His moisturising creams (£7.50), Frankincense & Cinnamon Beeswax lip balms (£3.95) and furniture polish (£4.50) are handmade in a “prayerful way” with the produce from the Abbey’s resident bees. “Whenever you begin any good work, you should begin with prayer. And while making the products, you raise your mind to God.” Devoting the body provides some respite from devoting the mind, he believes. “You’re giving your mind rest, and you’re using the whole body to help you to continue this search for God.”

The monks must remain mindful of their holy devotion. “Anybody who feels that they’re doing a service to the community, that they’re indispensable, or they’re making more money than any other member of the community with their craft should be taken off [production] straight away,” cautions Father John, “because it’s not good for his soul. It can easily fuel our vainglory.”

It’s a principle that stands in stark contrast to perhaps the most famous of all monastic pharmacies, the flower-garlanded, marble-floored Officina Profumo-Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella, housed in a 13th-century Dominican friary in Florence. The church and its friary were established in 1221, and the friars soon began “experimenting with herbs and flowers grown in the monastic garden, creating soothing balms, elixirs, and other medicines”, says CEO Gian Luca Perris. One of the earliest products was the Rose Water intended to treat the plague at the height of the Black Death, first sold in 1381. The Farmaceutica remained in the ownership of the church until 1866, when the property was confiscated by the kingdom of Italy, under whose ownership it remained until 1946 when Santa Maria Novella was privatised following the formation of the Italian Republic.

It still sells the Damask rose water (£35), along with other elixirs including tobacco-infused shaving cream (£45), a bergamot-scented enzymatic peeling mask (£90) and a children’s line of diaper cream (£20) and gentle cleansing water (£25). The farmaceutica now has around 100 stores worldwide, but the original friary, with its frescoes by Paolino Sarti, remains a cult destination. So much so that investment company Italmobiliare decided to complete its purchase of the brand in 2021, buying the final 20 per cent stake for €40mn. “One of the rooms in the Florence store overlooks the cloister of Santa Maria Novella,” observes Perris. But the monastery “is no longer involved in the production of the products”.

From a friary without its monks to nuns without a convent. Found on an acre of land in California’s central valley, The Sisters of the Valley is a collective of non-religious, spiritual “nuns” who live and work communally, growing marijuana to produce CBD products. “We’re not a religion, we’re just all about women owning businesses, and we live a monastic lifestyle,” says Sister Kate, who founded the Sisters of the Valley in 2015, after being inspired to explore communal living by a Native American tribal gathering she attended in the San Joaquin Valley.

In its modern Californian incarnation, the “order” is supported through making white-sage bundles ($10.75), lavender spray ($21.50), Clary Sage Spray made with distilled moon water (water charged with lunar energy) and witch hazel ($21.50), Arnica soap ($7.20), CBD tinctures (from $24.69) and salves (from $10.51) to aid sleep and pain relief. They grow everything they can, and harvest with the cycles of the moon. Sister Kate’s Catholic schooling shaped some of their practice. “We’re very much about putting prayer into the work we do, and working in a prayerful environment,” she says.

Rather than ora et labora, they take a vow of “solace”: Service, Obedience, Living Simply, Activism, Chastity and Ecology. “I’ve always been spiritual,” says Sister Kate. But she’s realised that for her, “meditating and manifesting is more powerful than praying to a god. Manifesting is creative energy.” It’s her own version of the Catholic sisterhood that educated and inspired her as a girl.

It’s a different lifestyle from that of Father Avakum or the monks at the Abbazia di Praglia, but there is a shared ethos. “We want these products to be things that people will buy that will help them feel good about themselves, in their physical wellbeing,” says Father John. “That was perhaps the fundamental inspiration: to know that the products are going into someone’s home from a monastery where God is the centre of everything. Hopefully the people who use them are inspired to be open in a new way to hope, to love.”

Comments