Is Suntory still king of Japanese whisky?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

You come face to face with drinks history as soon as you alight from the train in Yamazaki, a town just outside Kyoto. Opposite the station, behind neatly clipped hedges, sits a little wooden tea house, the only surviving design by Sen no Rikyū, the 16th-century creator of the Japanese tea ceremony.

A short walk away, on a forested slope, lies Japan’s oldest malt whisky distillery, Yamazaki. Founded in 1923 by Shinjiro Torii, the founder of Japanese drinks giant Suntory, this red-brick building celebrates its centenary this year.

Yamazaki’s great age may come as a surprise – particularly if you’re one of the many westerners who only learned Japan made whisky when they saw Lost in Translation (2003), in which a bemused Bill Murray attempts to shoot a Suntory whisky commercial: “For relaxing times, make it Suntory time!”

Japan has actually been making whisky of sorts since the mid-to-late 19th century. Yamazaki was its first purpose-built distillery. Its raison d’être was to make malts for blending, and it remains an important component of Japan’s best-selling whisky Suntory Kakubin, a blend you’ll find everywhere in the ubiquitous “Kaku high”, or Kakubin highball, served in a tall glass with soda and ice. It wasn’t until the early Noughties that Japanese whisky gained wider recognition, following a spate of wins for Yamazaki and its blended stablemate Hibiki at global competitions. It lit the touch-paper for demand, and prices duly spiralled.

Japanese whisky is made in a manner very similar to Scotch; the malted barley is imported from overseas. So what makes a whisky characteristically “Japanese”?

“It’s two things,” says Shinji Fukuyo, Suntory’s chief blender, over a tasting at the distillery that looks out on a lush forest of bamboo, firs and maple trees. “One is nature. The water here is very pure, very clean and mild. Scottish water has more organic compounds in it, so it has a stronger character. Our climate also changes drastically from hot and humid summers to very cold, dry winters, which accelerates maturation, giving us a much deeper, well-matured whisky. But it’s also craftsmanship. We think our work is very precise and very detailed. If we look at other Japanese industries such as car manufacturing or watchmaking or industrial arts like pottery or lacquer wares, it’s all very precise, detailed work.”

Another thing that tends to distinguish Japanese distilleries is their versatility – unlike Scotch whisky companies, which have a tradition of trading whisky for blending, Japanese companies are much more geared towards self-sufficiency. In the spirit of tsukuriwake – or “artisanship through a diversity of making” – Yamazaki uses various strains of barley, eight pairs of copper stills in varying shapes and sizes, and six different types of cask, which gives Fukuyo a big spectrum of malts to play with. It allows him to build, almost pixel by pixel, the intensely fragrant flavour profiles of Yamazaki and Hibiki.

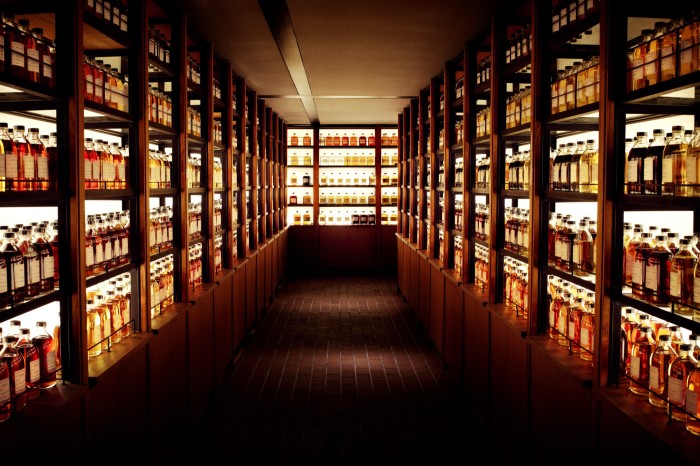

In the cool, dark warehouse, I walk among ghostly whitewashed casks coopered from mizunara, or Japanese oak – another important part of the Yamazaki recipe. “It gives our whisky a very oriental note,” says Fukuyo. “It’s spicy but incense-y, like a temple washed by rain.”

Five great whisky bars in Japan

Analog, Tokyo

One of Tokyo’s growing band of “listening bars”, where you can leaf through vinyl, dram in hand. I went for Hibiki Harmony over an ice ball, and The Strokes’ “Is This It?”, paired with popcorn chocolates and truffle crisps served in repurposed 7-inch.

Marugin, Tokyo

This rough-and-ready izakaya bar was the first to serve Kaku-Highs on draught. A tankard of whisky and soda sounds insurmountable, but trust me, it’s mostly ice. Extremely refreshing with a skewer of chargrilled peppers or quail eggs.

Apollo, Tokyo

Just a few candles away from total blackout, and hosting a mere 15 seats, this basement bar in Ginza is incredibly atmospheric. Quality, not quantity, dictates the menu. Tom Waits is on the turntable. Immaculate highballs are served with hand-carved ice.

Caamm, Kyoto

Crammed floor-to-ceiling with bottles and memorabilia, Caamm is like the den of a very cool hoarder. Choose from more than 1,000 whiskies – some rarely seen outside Japan, such as the Suntory Essences – then retire to one of the low-lit nooks.

Bar High Five, Tokyo

Cocktail fans come from far and wide to see proprietor Hidetsugu Ueno in action. If you’re very good, he may even carve an ice gem for your dram. Whisky drinks include a delicious highball of Hakushu, soda, honey, lime and yellow Chartreuse.

To mark the distillery’s centenary, Suntory has bottled a special-edition Yamazaki 18 (£1,600), aged entirely in mizunara; it’s aromatic and sweet, with notes of white peach, almond, orange zest, tatami mat and cedarwood. There will also be a limited-edition peated 18-year-old malt (£1,275) from Suntory’s other single-malt distillery Hakushu (which by coincidence celebrates its half-century this year). Distilled and aged in the cool climes of Japan’s Southern Alps, it’s as lush and subtly smoky as a spent campfire covered in dew.

Suntory’s motto is yatte minahare – a saying that embodies the concept of always moving forward. And Japanese whisky is now experiencing a dynamic period of growth. This year sees the launch of two ambitious distilleries: Komoro is the brainchild of Koji Shimaoka, a former MD at Citibank, who tells me his aim, long-term, is to build a whisky business to rival Suntory; the other is the Karuizawa Distillery, whose heavyweight backers include the owner of ultra-luxe Japanese whisky retailer Dekantā, Teaghlach Holdings PLC.

Rules were recently tightened regarding the definition of “Japanese whisky”. From next year, only those that are fully fermented, distilled and aged in Japan can legitimately use the term (blends that include whisky from overseas – of which there are a surprising number – will have to drop the word “Japanese’’). Some craft distillers like Chichibu, meanwhile, have been exploring using more local materials including Japanese barley and peat. “A 100 per cent Japanese whisky is an interesting concept,” says Fukuyo, “but not if it comes at the expense of quality. We will keep on innovating but that will always be our first priority.” @alicelascelles

Comments