Cowboy culture is everywhere – and it’s way more inclusive

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On a sodden Tuesday night in Brooklyn, bundled up twenty- and thirtysomethings rustle into a ballroom. The points of cowboy boots poke out under jeans and peasant skirts; Stetsons stud the sea of heads. Inside, beneath shards of light spun from a gigantic disco ball, they dance. Specifically, they line dance. A man in cow-print chaps, a black leather thong and fringed capelet kicks his heels high. The hundreds-strong crowd toe-tap, clap, whoop and slide through the set moves.

This is Stud Country, the queer line dancing and two-stepping party founded by Sean Monaghan, 36, and Bailey Salisbury, 39. After amassing a cult following in LA (including singer and actress Reneé Rapp and indie supergroup Boygenius), where it began in 2021, Stud Country now hosts regular parties in New York at Brooklyn Bowl and Georgia Room. Across the city, everyone is line dancing in clubs and bars – at classes at the Ukrainian East Village Restaurant; at an LGBT+-led Hell’s Kitchen club that’s been going for nearly three decades; at a honky-tonk party in Queens recently headlined by singer and actress Lola Kirke.

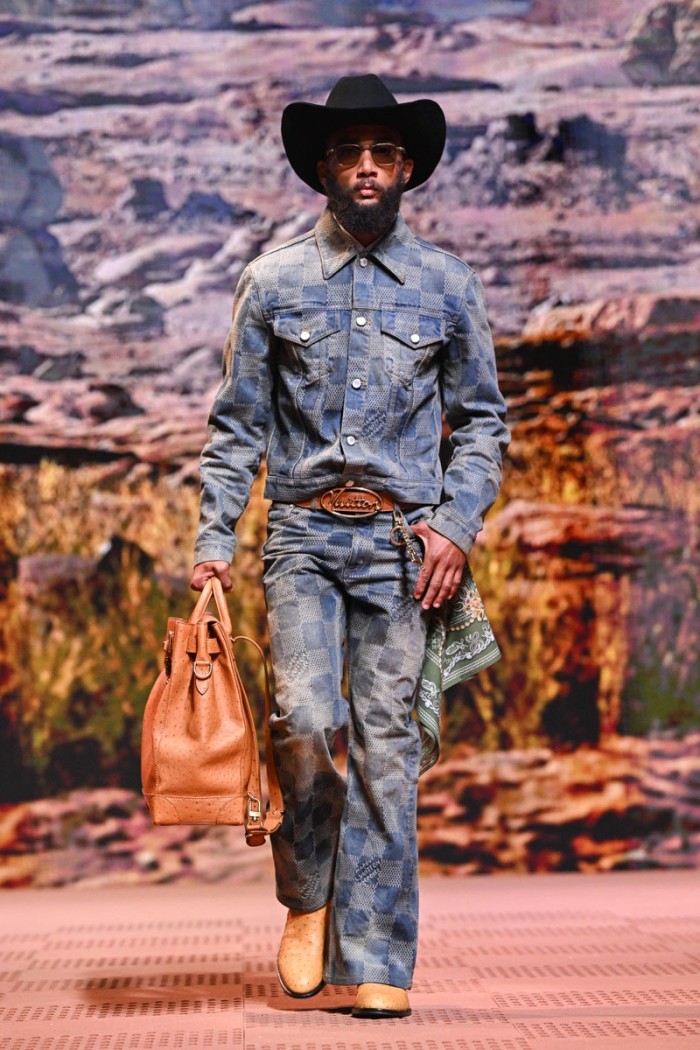

Cowboy culture has been riding a wave that recently crested with – in quick succession – Pharrell Williams’s western collection for Louis Vuitton, Lana Del Rey’s announcement of a country album, and Beyoncé’s long tease of her new album Act II: Cowboy Carter. Molly Goddard nodded to western wear in her AW24 collection with yoked shirting and embroidery. Edward Crutchley offered tapestry cowboy hats and laced leather. And Stetson has been struggling to keep up with the demand for its hats.

For anyone who thinks line dancing is for dour southern conservatives, Stud Country proves them joyfully, defiantly wrong. “I say Stud Country is explicitly queer but not exclusively queer,” says Monaghan at an East Village café as a chihuahua in a pink puffer hoodie squirms on Salisbury’s lap.

The two friends from the Bay Area punk scene have a background in dance – Salisbury’s mother was a ballet teacher, and Monaghan did Irish dancing competitively. When Salisbury moved to LA about seven years ago, they started line dancing at Oil Can Harry’s, then the oldest gay bar in the city. When it closed during the pandemic, they were “devastated”, and decided to keep it going themselves. Classes on Zoom evolved into regular parties and workshops in New York, LA and San Francisco, where Salisbury now lives.

At Stud Country, there are “leaders” and “followers” rather than traditional men-women pairing. “What makes it queer is the partner dancing,” says Salisbury. “Past generations were arrested for same-sex partner dancing.” When it’s time to teach the night’s first line dance, attendees sardine themselves in messy rows on the dancefloor, Monaghan and Salisbury run through the steps and the crowd follows, mostly treading on each others’ toes. There are two lessons. The rest of the night is given over to dances people know the steps to, mesmerisingly in sync as they slide and stomp across the floor.

Line dancing can be complicated, but Stud Country endeavours to keep it accessible: “The more people on the dance floor, the better,” says Monaghan. Most of the music is country (Keith Urban, Luke Combs, now Beyoncé) but not all of it (Ed Sheeran, Stevie Nicks). Since it’s choreographed, it’s easy for non-dancers to get involved. “You learn the choreography, you make it your own, you freely express yourself, you leave exhausted but happy. What’s better than that?” says Rona Kaye, who has been teaching line dancing in New York City for 31 years.

Kaye also lists the health benefits of line dancing: it’s cardiovascular, and it exercises your memory. Candace Maxwell, 33, an actor who attends line dancing classes in the East Village, adds that she considers it “meditative”. “It forces me to be present,” she says, “I can release – and it’s also fun.” Others come for the social element.

“It’s growing exponentially, with or without us,” says Salisbury. “But the etiquette and the history and the tradition is so important [to remember],” she emphasises. She and Monaghan often give impromptu history lessons, for instance explaining how Stud Country’s style of two-step – slow-slow-quick-quick – has its roots in gay convention. “It’s more meaningful when it’s connected to the history,” says Monaghan. For them, dancing is about community and culture – and the community is the culture; that history of clubs, like Oil Can Harry’s, where LGBT+ people line danced and two-stepped in a safe space.

Back in Brooklyn, Amanda Chesin, a 27-year-old software engineer originally from Arizona, explains the club’ s appeal. “I felt excluded from line dancing, because I felt it wasn’t for me,” she says. “Same with two-stepping – as a woman, to dance with another woman, I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing that somewhere else, but it’s cool to feel that comfort and that space here.”

Over the 20th century the forces of Hollywood, commercialisation, nostalgia and racism coalesced to create the archetype of the cowboy, a white, masculine folk figure onto whom an American national identity could be mapped, Emma McClendon, an assistant professor of fashion studies at St John’s University, explains. However, she notes, cowboy culture and clothing has a diverse mix of influences: the Mexican vaquero tradition, and the real-life cowboys, some of whom were Indigenous, and as many as one in four were Black. “I feel like when you see cowboys portrayed, you see only a few versions,” Pharrell told press after the Louis Vuitton show, for which he worked with Lakota and Dakota artists. “You never really get to see what some of the original cowboys really look like. They look like us, they look like me, they look Black, they look Native American.”

Stud Country may be political, but primarily, it’s social. It’s a place where dancing alone becomes something communal. “Dance is an opportunity to make a connection with your body and other people,” says Monaghan. It opens the door to friendship, romance and community. To the swagger, sexiness and exhilaration of the group dance; the intimacy of touching a stranger in the partner dance. “And everyone’s hot,” Salisbury laughs.

Comments