In search of the south-Asian style icon

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

For a while when I was growing up there was Art Malik and that was it. The British-Pakistani actor was the only brown man with any presence in this country. Or so it seemed to me. Depending on your age, you might know him as the Islamist terrorist in True Lies (1994) or the hospital consultant in Holby City (2003-05). But in the ’80s, Malik was famous for playing Indian heartthrob Hari Kumar in the TV adaptation of Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, The Jewel in the Crown.

And that was the problem right there. As a young British Asian coming to terms with his identity, I wanted nothing to do with what another Hari – novelist Hari Kunzru – called the “Raj theme park”. Likewise, I ran a mile from overly romantic notions of India – the mysticism and exoticism that white folk were so eager to extol and which Hanif Kureishi satirised in his 1990 novel The Buddha of Suburbia. I was young, insecure and growing up in the shadow of London’s North Circular. What use did I have for patchouli-scented caricatures and Empire?

Of course, there was Bollywood. Plenty of brown faces there. Long before Zee TV was being streamed to Non-Resident-Indian households across the country, my father accessed the latest releases on VHS from our local Indian grocery turned video shop. But Bollywood always seemed remote to me. I didn’t speak the lingo. And its vision of masculinity – too many mullets for a start – was not something to which I aspired. “When we only see ourselves as stereotypes that have no bearing on our lived experience, we operate without reflection,” writes Nikesh Shukla in his memoir Brown Baby. Well, where was my reflection, I wondered?

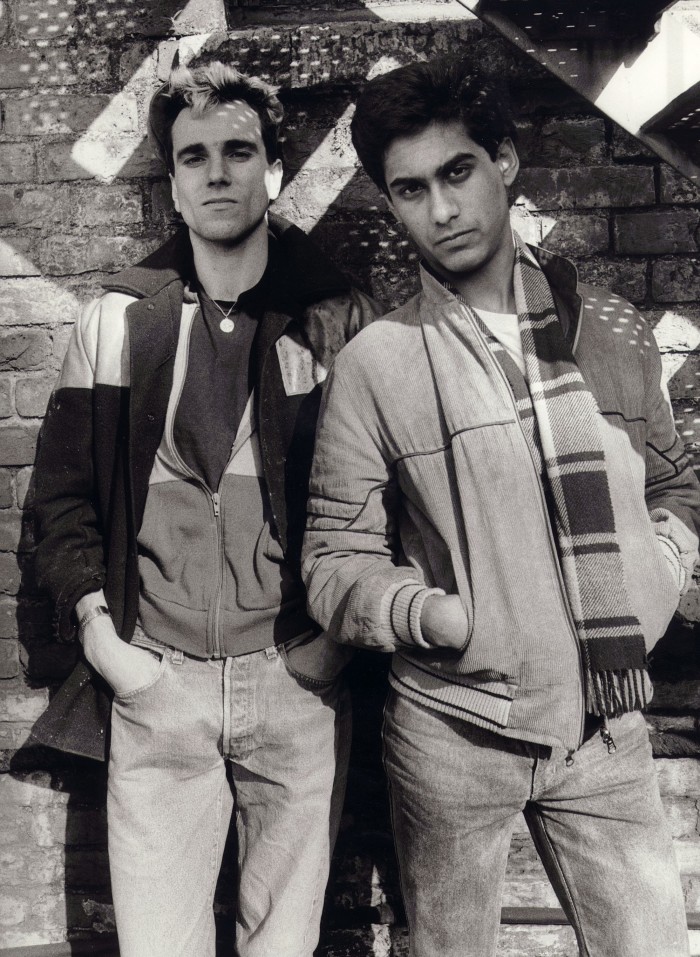

Things got worse as a teenager. Now I had aspirations. I knew what I wanted to be: not a doctor like my parents. And well-dressed. I had discovered fashion. Where were the Brit-Asian role models for that? I tore out looks from men’s fashion magazines. The faces were never brown. It didn’t really bother me. Though perhaps, in hindsight, it did. Western culture said being brown was uncool. Especially if you were male. We were the boffins. The skinny sidekicks. I, like many, was haunted by characters such as Ben Jabituya from Short Circuit (1989), the robotics engineer with an Indian accent whom I only recently found out was played by a white dude. Brownface was still acceptable in the ’80s. Even Alec Guinness was at it (in 1984’s A Passage to India). Thank god for Hanif Kureishi, who dared to show contemporary British Asians as not only sexual and desirable but also queer. Almost 40 years after its release, My Beautiful Launderette still feels radical.

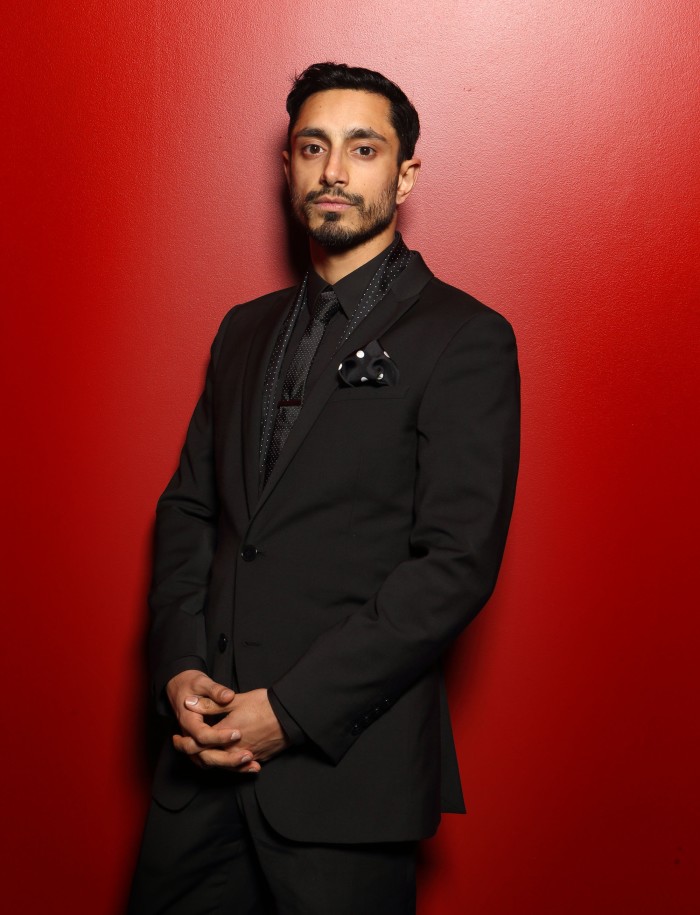

But in real life, where were all the stylish south Asians? Where was my set? Looking back, I feel envious of British-Indian fashion designer Rav Matharu who had a clique of like-minded Asians in his hometown of Leeds. Matharu, 40, is the founder of bespoke luxury streetwear brand Clothsurgeon and the first designer of south-Asian origin to open a store on Savile Row. His clients include Riz Ahmed and A$AP Rocky. After a stint as a professional footballer, he worked in retail, where he developed a friendship group of “cool Asians who knew how to put an outfit together. It was about being ahead of the curve and styling things differently.”

I see a lot of myself in his story. He wanted to go into fashion. His father was against it. He compromised and applied to be an architect before deciding to “follow my dreams” after all. Wanting to read English at university, I had to make overtures to my parents about converting to law. I later reneged on that and went into journalism. It’s a common refrain – creatively minded south Asians diverted from their preferred professions towards more “respectable” trades such as medicine or engineering. The dearth of brown faces in creative industries only compounds the problem. “Look at this country. Where do you see yourself? You have to be where you can see yourself,” Shukla’s mother berates her son in Brown Baby on learning he wants to be a writer. Reading that, I cringe in recognition.

Of course, there have been stylish figures to emulate, but until recently they have been still vanishingly few. “Actor and designer Waris Ahluwalia from the Wes Anderson movies was the only one I could look to who I thought had effortless style and taste,” says Matharu. Filmmaker Aaron Christian, 38, who grew up in east London and runs his own agency AC Studios (clients include Church’s, Dunhill and Emporio Armani), recalls attending menswear shows as a young filmmaker and spotting only a few stylish south Asians on the circuit. As a brown man who’d been passionate about clothes from an early age, it struck him: “Surely there must be more.”

It was this impetus that saw him launching The Asian Man, first on Tumblr then as an Instagram feed (@theasianman_) celebrating stylish south-Asian men. When the feed launched in 2014, sourcing pictures of suitable candidates online took up to two months. The men were out there. But few were comfortable putting themselves in the public sphere. “In the past two or three years, it’s really picked up,” Christian reports. “Now I’ve got daily posts lined up for the next eight months.”

He puts it down to younger, braver second- and third-generation south Asians who are “not waiting for permission and are more expressive in how they see themselves and putting images out”. Judging from responses, the site has helped a lot of British-Asian men shake off insecurities. “A lot of people started to believe those [regressive] stereotypes (such as the asexual nerd) and be limited by them,” he says. He is currently working on a book of The Asian Man, out later this year, which will showcase a range of men with different styles. In dress sense, as in other things, “we are not a monolith,” he says.

But stereotypes run deep. Delhi-born, London-based designer Ashish Gupta, 49, who has made clothes for Beyoncé, Hunter Schafer and Rihanna, and is the subject of a fashion retrospective Ashish: Fall in Love and Be More Tender at London’s William Morris Gallery from April, recognises the impact India has had on his work. “But it took me a long time to bring acceptance towards my roots and my cultural references because I did not want to be stereotyped,” he says. “When you try to create your own language through your work, it always involves fighting and breaking down stereotypes.”

Flying in the face of preconceptions that Indian fashion be colourful or embellished, LVMH Prize-nominated menswear designer Kaushik Velendra, 32 – who grew up in Bengaluru and moved to London in 2014 – has leant heavily towards black in his designs, using a colour “the whole world is comfortable with”. Visitors from India are sometimes surprised not to find sherwanis or kurtas in his collections. There was also an assumption among his peers at Central Saint Martins, where he graduated in 2019, that he would simply become a tailor. (Matharu notes a similar expectation: “We’re meant to be the machinists, the ones who supply the cloth, not the designers who take centre stage,” he says.) In fact, Velendra had loftier goals “to become the next Indian-originated Dior”. For that there were no role models. He hopes to become one himself. Role models are important, he says, not only for the aspiring individual but also to “prove to your family or culture that there is a path to follow”.

When Matharu opened his store on Savile Row last August, it was celebrated by the south-Asian community. They understood the significance of being represented on that street. “It was a beautiful moment,” says Matharu. He was contacted by a woman of British-Pakistani descent whose tailor father had once applied for a job on Savile Row. “They told him he could have the job but he would get half the wage and could never come upstairs especially when a client was in the building,” Matharu says. “She told me, if her father were around to see this moment, how happy he would be.”

But for all the progress made on runways, in campaigns and behind the scenes, I find myself echoing Velendra’s impatience: “We need more,” he says of brown faces in fashion. “We need hundreds. Thousands. What we have now is not enough.” Still, when I scroll through social media (style feeds, street fashion) and spot a brown face – which is more often than ever – I cheer. Then I stop to examine his trousers or his shoes or the coat he has on, and think, “Where can I get one of those?”

Comments