Untapping the inner beauty of Budapest

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Seven in the morning at Budapest’s Rudas thermal baths on the banks of the Danube, and ribbons of steam are winding up from the huge 16th-century octagonal central bath, past hefty limestone columns, to the domed roof. Sun streams down through small stained-glass skylights in coloured tendrils. Together with 15 or so other women, some in swimsuits, others in cotton aprons, I am slowly working my way round the outside of the room on a therapeutic plunge circuit of four corner pools. Giant taps gush forth mineral-rich waters that charge up from the ground deep below. Each bears an ancient stone marking, reading 28º, 30º, 33º and 42º. The 42º corner pool is so hot that I only last five minutes – 28º is a welcome relief. After several laps, I sink back into the waters of the central safe haven, making sure to stand beneath the fountain, its mouth beautifully distorted by centuries of mineral precipitation. Maybe it’s because I’m in an ancient space, away from the office, or technology, or stress, or maybe it’s because I want to believe. But I can feel something magical in these waters.

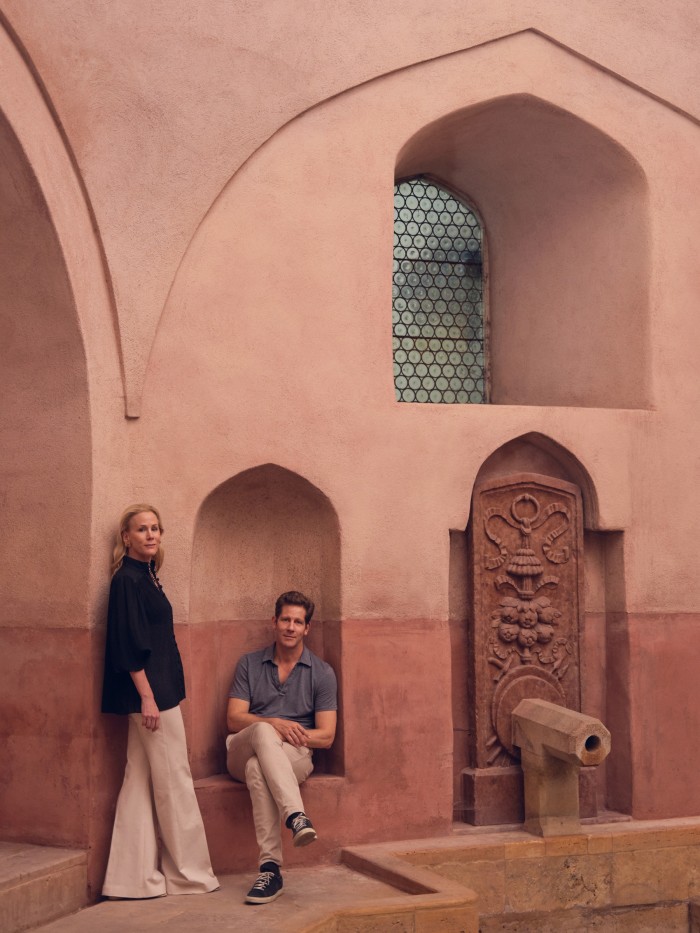

I have been invited to Budapest by Stephen and Margaret de Heinrich de Omorovicza, founders of Hungarian skincare brand Omorovicza, whose products use the city’s thermal waters, together with a patented “healing concentrate” – created by fermenting the waters to harness their beneficial minerals – and treated local mineral-rich mud. “The whole point of everything we are doing has to do with the geology of the place,” Stephen said to me before I arrived here. “The springs in Hungary are grotesquely rich in minerals because of its unique geology.”

The Triassic geological formations of the region – specifically the Carpathian Basin, which is divided by the Danube – means more than 10,000 years’ worth of rainwater runs through the carbonate rock on the Buda side of the city and combines with a small amount of sea water captured (and mineralised) in the rock deposited in Miocene times (about 23 to 5.3 million years ago) on the Pest side. “There’s a massive fissure right by the Danube, which means that these waters plunge all the way down to where it’s very, very hot,” says Stephen. “And they come back up charged with minerals.” Bathing in them, adds Margaret, gives you a “sense of vitality” – something the couple believe they have captured in their treatments. This September, they are bringing those treatments to a new Omorovicza Institute on London’s South Audley Street, a standalone sister to the Budapest flagship.

There are more than 1,000 hot springs in Hungary and 100 in Budapest, and there have been healing baths since the 16th century, built during Ottoman rule, a 160-year period when the Turks formalised springs once visited by the Celts and later the Romans by creating hammam-inspired spaces. A sign at the Rudas baths commemorates their completion under Pasha Sokoli Mustafa, governor of Buda between 1566 and 1578. Many were updated during the Austro-Hungarian era in grand Szecesszió (art nouveau) style, but the rituals continue just as they have done for 450 years.

Bathing is a huge part of Hungarian life. At one end of the spectrum, doctors prescribe visits to these variously calcium-, magnesium-, sodium-, sulphate- and fluoride-rich waters to cure ailments including joint aches and arthritis. At the other, baths are part of a quasi-club culture, serving alcohol at “sparties”. At the resplendent 1,900-capacity neo-baroque Széchenyi Palace baths in the City Park, which stays open until 2am, I see that one of the many baths is exclusively reserved for beer drinking. Outside, gentlemen with bronzed bellies sit around playing Magyar kártya – cards beautifully decorated with leaves, acorns, bells and hearts. Others play chess on limestone boards fixed in the water. Children eat ice creams. Spa life is life.

It’s also written deep into the Omorovicza DNA. It was on a trip to the Rácz Fürdő, the oldest thermal baths in Budapest, around 20 years ago, that Stephen discovered that his ancestor, Dr Janos de Heinrich de Omorovicza, had been an eminent 19th-century balneologist who opened this set of five public baths in 1861. It was a revelation. Stephen’s family had left Hungary after the communists took control after the second world war. “I used to hear a lot of stories about Budapest because people loved to talk about life in Hungary before the war,” he says. “But nobody ever mentioned a bath.”

Walking around the Rácz today offers a gothic fantasy of decadence and disarray; it has been closed for more than a decade but the 19th-century grandeur is manifest. I wind down a debris-covered peach-stone staircase with decorative iron banisters to the baths. At every turn is ornate Szecesszió ironwork, from birdcage-like showers to sculptural taps. Black, white and pink marble floor tiling encircles the bathing space. Neoclassical sculptures and relief carvings line the passageways, by turns crumbling and perfectly composed. Walls and ceilings are painted in Klein blues, blush and sandy tones. Much of the paintwork is peeling. Taped to the walls are reconstruction plans for a grand reopening pencilled for 2024 (including Omorovicza treatment rooms). It’s part cinematic, part museum vaults, part dream.

Omorovicza was born of this legacy. Seduced by the romantic tales told by his grandparents, Stephen, who grew up in Switzerland, had returned to Budapest, and was CEO of a biometrics start-up in the city. Together with his wife Margaret, the chief of staff at the US embassy in Hungary, who began to notice the benefits of the waters on her skin, they began to wonder if there was a way of taking Dr Janos’ belief in the healing power of the waters and “transforming those minerals into something the skin can absorb”. The answer, reached with scientists at the same Nobel Prize-winning laboratory of dermatology that discovered vitamin C in 1928, was bio-fermentation, which takes the thermal water and adds yeast to create a complex compound of minerals that is easily absorbed into the skin, deep into the epidermis. The result is the “healing concentrate”. This patented innovation, clinically proven to reduce transepidermal water loss and increase skin firmness and elasticity, was launched in 2006 and is now used across the entire line.

I am excited for my facial at the Omorovicza Institute, a high-ceilinged boutique and therapy rooms on Andrássy út, a grand avenue nicknamed the Champs-Elysées, dating to 1872, that, like many roads built in the Austro-Hungarian era, draws upon Paris’s aristocratic boulevards. Up the street is the French Renaissance-style Drechsler Palace, the former ballet institute that has been renovated by the W hotel group, a sensuous mix of 19th-century architecture and the jewel-toned hues and contemporary design that the W has made its signature.

My Omorovicza facialist, Adrienne, was the first specialist to join the company when it launched in 2006 and was instrumental in the development of products and protocols. She analyses my skin and prescribes a copper peel to remove dead cells, vitamin C eye cream, a deep-cleansing mud mask using treated local mud mixed with white clay to exfoliate and draw out toxins, application of the healing concentrate serum and a 20-minute Hungarian facial massage. Facial gymnastics may have gone viral on TikTok, but the techniques have been practised by Hungarian and Austrian facialists for more than 150 years, laughs Adrienne, who trained for three years in the skill. “Massage is part of the active healing… so the concentrate can really penetrate,” she tells me. “I don’t know why no one ever used these healing products in cosmetics before. It’s a genius idea.” The experience leaves me feeling invigorated and my skin lifted, plumped and glowing.

I particularly love the Queen of Hungary mist, inspired by a 14th-century queen’s bespoke orange blossom and rosemary scent, said to be the first modern perfume. Likewise the vitamin C serum that draws upon biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi’s discovery. Most intriguing is the Moor Mud collection, which includes treated mineral-rich mud from the peat bogs around Lake Héviz.

The scenic road south-west to Lake Héviz weaves through fields of wild lavender, vineyards, and farmland filled with corn, wheat and sunflowers. We wend past thatched cottages, stern medieval castles atop rocky hills, and along the 78km length of Lake Balaton, which sits on a volcanic soil bed. People fish for 30kg catfish, swim and feast outdoors.

Héviz is the world’s largest bioactive natural lake, whose spring waters, dating from volcanic activity 200mn years ago, range from 22ºC to 38ºC. Thick forest surrounds the 4.4-hectare surface; a turreted neo-baroque building appears to float over its lily pad-blanketed waters; groups of people float about while others lounge on the banks, sunbathing, reading, sleeping.

Legend has it that the nanny of a paralysed child in the Roman period prayed to the Virgin Mary and the result was this spring of healing water; the child grew up to become the Roman emperor Theodosius. True or not, a bathing culture has flourished since Roman times. Rita Vas-Barna, balneologist and head of treatments at Héviz, tells me that the waters’ power is held in the combination of their heat, chemicals and hydrostatic pressure. The waters are so plentiful they replenish themselves every three days, she adds. Meanwhile, the mildly radioactive mud used in treatments at Héviz is rich in radon, sulphuric substances, calcium, magnesium, bicarbonate zinc, copper and fulvic acid, and is taken from a local source at Alsópáhok (on rotation, so it can replenish itself), milled and sterilised, and heated to 42ºC. The lake, Vas-Barna says, is particularly beneficial for those with psoriasis, burns and joint pains.

I am led to a lakeside treatment room surrounded by simple canvas screens, where a therapist and a wooden bucket of mud await me. The all-over body massage is firm, thorough and deep. Then comes the mud – thick, warm, soft, grainy and black (thanks to the humic acid), it is both exfoliating and tingly; it feels active, almost alive. I am wrapped up like a parcel so it can soak into my skin. When she returns, the therapist ladles sulphurous water directly from the lake to douse me down. My skin is silky-soft.

Alongside the healing blue‑green algae found in many other lakes, which are often used in skincare products, Héviz contains two more algae species that are great for the skin. Together with the natural postbiotics (substances that probiotic microbes produce) in the mud, it’s “perfect for the microbiome of your skin”, says Stephen. “It restores it by bringing all these bacteria to bear on the skin.”

It might seem bizarre for a luxury beauty brand but, drawing from Lake Héviz’s ancient rituals, Omorovicza takes mud from local peat bogs and treats it so it can be used in the Moor Mud line. The microbial species have been working away for millennia, not something you can easily recreate in a lab. It’s potent stuff. “When we started formulating,” says Stephen, “we initially had it at a 10 to 15 per cent mud concentration, and it was just painful. So we dialled it down.” The cleansing mask combines the mud with white clay; the thermal cleansing balm, to remove make-up, mixes it with sweet almond oil. Much of the line tingles to the touch; like the mud wrap at the lake, it somehow feels alive.

“Skin therapy is how we deliver on this promise of the geology,” concludes Margaret. “We do it through two pillars: through the healing concentrate and balneotherapy treatments.” Budapest in a bottle, you might say.

Beatrice Hodgkin travelled as a guest of Omorivicza. One-hour facial at the Omorovicza Institute, £125; 60 South Audley, London W1. Day passes to the Rudas baths, from Ft5,900 (about £13.15). Day pass to Lake Héviz, about £17; mud massage, about £25. Rooms at the W hotel start from £390 per night

Comments