Lack of clear targets hinders impact investing in education

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Arne Duncan has two confessions from his time running the Chicago Public Schools education authority: frustration that the system had previously been described as the worst in the US, and uncertainty over what drove its elevation in one recent assessment to the fastest improver in the country.

“No one really knows for sure what changed,” he admits. “But I would put a huge emphasis on hiring high-quality principals able to manage resources and attract good teachers; creating meaningful evaluation; offering after-school and summer-school programmes; and providing early childhood education.”

That frank analysis from such a senior official — who went on to be former US president Barack Obama’s secretary of education — highlights how school reform is complex and politically sensitive. Fierce debate continues on how low Chicago had fallen and how far it has since risen, let alone the factors behind the improvement and the full consequences of change.

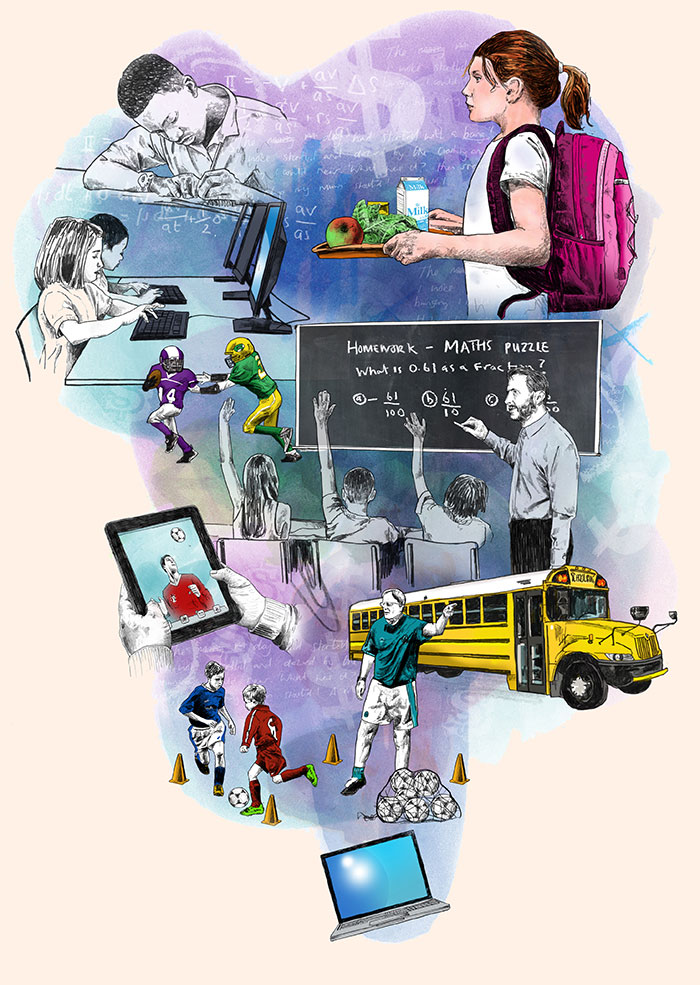

While there is plenty of scope for impact investing in innovation and investment in education in the US and around the world, the lack of clarity on what to do and how to do it shows just how difficult an area it remains.

Duncan says he believes there is potential to make a difference for social impact investors, such as The Rise Fund, to which he is now a senior adviser.

“My priorities are excellence, equity and scale,” he says. “We can’t just reach the wealthier children, and while pilot programmes are good, we want to get to millions of kids.”

There is no doubt that impact investor interest in education is growing. Rise’s own investments include DreamBox, which personalises maths teaching for students in the US, and Renaissance, software to help teachers with practice and assessment of maths and literacy skills in the classroom.

In the UK, Bridges Sustainable Growth Funds, an impact investor, has also explored digital technologies in the classroom. But Oliver Wyncoll, a partner, cautions that while “it is generally not too difficult to know whether a product works and generates a better outcome, the challenge is how you scale it, given inertia and the number of decision-takers involved”.

Bridges has also explored impact in education from a different angle. It recently took a stake in Innovate, a UK provider of healthy school meals. “We identified obesity two years ago and looked for solutions,” says Wyncoll. Once Bridges has made an investment, he adds, it makes sure the impact and the financial outcomes are closely co-ordinated.

The biggest potential beneficiary of impact investing in education, if only because of the gulf between need and funding, is probably Africa. An analysis by Caerus Capital, a Washington DC-based consultancy, suggests there is great scope on the continent, partly because of the very low levels of school enrolment and achievement: some 30m African children are not receiving any form of schooling, and up to 40 per cent are not meeting basic literacy and numeracy goals.

Equally, more than a fifth of children and young people on the continent are already being educated in the private sector, and Caerus forecasts a need for $16bn-$18bn in private capital over the next five years. It has identified opportunities in “core delivery” in schools and higher education, and in “ancillary services”, including teacher training, supplementary education (such as after-school-tutoring, language learning and test preparation), education technology, student finance, institutional finance and publishing.

Yet, as the report points out, such investments risk exacerbating inequalities, cherry-picking the best students and teachers while undermining government provision and leaving the poorest further behind. It argues that access, quality and relevance are key.

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, a fellow at the centre for universal education at the Brookings Institution think-tank in Washington DC, argues: “Impact investing is most appropriate at the two ends of the spectrum — in early pre-school and post-school education — where we see a proliferation of non-state providers.” Few of the rigorous analyses of educational interventions have demonstrated clear or replicable impact, says Gustafsson-Wright, and it is difficult to identify a route map, in part because there are so many factors in low-income countries that can influence outcomes, from menstrual hygiene and nutrition to cultural resistance to school attendance and difficulties in recruiting teachers.

Future challenges for impact investment in education will, she suggests, include strengthening the evidence base to demonstrate what works, and making it easier to bring entrepreneurs and funders together “We’re not quite there yet,” she says. “There is a disconnect between opportunities and investors interested in financial returns. The complementary pieces of the puzzle could be more efficiently harnessed.”

Impact bond brings hope for Indian girls

Donors to the education sector often make their funding conditional on outcomes, but Educate Girls has come up with a new model. The non-governmental organisation, which was set up to improve the education of marginalised girls in rural India, concluded a pioneering three-year “development impact bond” this summer to tap private investment.

The bond was designed to fund additional support to reduce the large number of girls aged six to 13 in Rajasthan who were not attending school, resulting in a failure to realise their potential and often in child marriage, which risks their health and limits their opportunities.

Educate Girls received upfront working capital from the UBS Optimus Foundation, was evaluated to track outcomes against a “control” group of villages not provided with the additional measures, and triggered payments from the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation if it achieved its targets.

This approach involves a package of measures, including detailed surveys, recruiting volunteers to visit households, teaching support, counselling and a new child-friendly curriculum.

“I was a bit nervous when at the end of the second year it seemed we would not reach our goals. But Educate Girls was able to modify the model after learning what works,” says Phyllis Costanza, chief executive of Optimus. “It was complicated and time-consuming, but we’ve learnt we can replicate it in much less time.”

It ultimately exceeded the goals of higher enrolment and improved learning. Optimus is now progressing with two other such bonds. Alison Bukhari, UK director of Educate Girls, says her organisation plans to expand its model to reach up to 16m girls by 2024.

The organisation is still raising funds, including from philanthropy, but has mixed views on repeating its use of bonds. “They are clever yet complex and we feel we do not have to go through such a cumbersome, multi-party, expensive instrument to deliver impact,” says Bukhari.

Network recruits Africa’s untapped talent

It was while working in Africa that Christina Sass spotted a significant mismatch which has turned into a for-profit training and coding business with significant social impact. She saw a gulf between surging global demand for developers and skilled but underused individuals across the continent.

“We constantly heard there were a lot of great employers unable to find staff, while people with degrees in Africa were struggling to find jobs,” says Sass, president of New York-based Andela. “Many of the large cities had the biggest pools of untapped talent in the world. There was a huge community of people interested in technology. Andela was about sustainably plugging into this incredible group.”

With operations in Lagos, Nairobi and Kampala, the company has grown to 1,200 employees since being founded in 2014. Its innovative recruiting, training and contracting model has attracted 150 customers. Its recruitment process includes tests for maths, problem-solving and responsiveness to feedback. Those who score well are invited to a “boot camp” to see how they perform in practice.

Successful candidates not only receive training. They are paid from the start and spend several months in coaching and “learning by doing” before being deployed as consultants for the full 40 hours per week while remaining part of the Andela network. Sass says salaries are above those of local start-ups and within four years staff are paid rates competitive with global consultants.

She estimates that the company’s consultants cost about a third of those in Silicon Valley, but compete on quality with those elsewhere in the US and south-east Asia. “What we don’t see in Africa is enough apprenticeships,” she says. “There is a lack of learning by doing.”

Yet the model seems to be working. The company is soon to open a Kigali office and has won backing from investors including the pan-African CRE Venture Capital, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

More examples of impact projects are identified each year in the FT/IFC Transformational Business Awards. Apply at live.ft.com/transformationalbusiness

Comments