Turin’s Pinacoteca Agnelli has become a world-class art space

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

After Fiat’s factory in Lingotto, Turin, opened in 1923, Le Corbusier hailed it an architectural masterpiece. Gloriously, it’s still here — deco concrete facades pierced with long windows; spiralling five-storey ramp whose crisp, symmetrical pillars and supports recall a cathedral’s arched vaults; and, on the roof, sweeping curved racetrack La Pista 500.

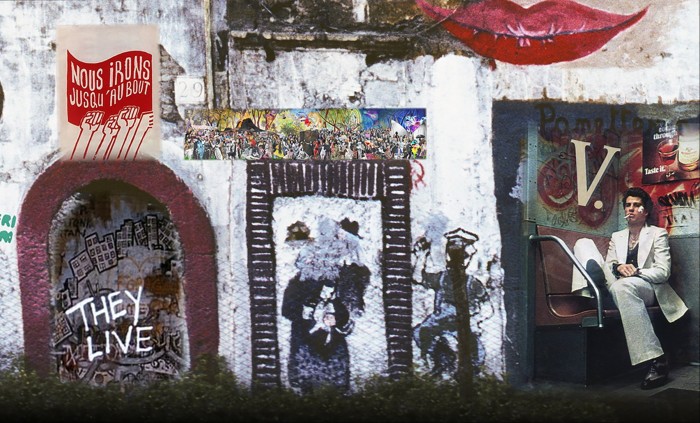

Instead of cars, hundreds of figures now rush and swarm across this space. In Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s 150-metre mural “Pistarama”, they enter from the left, where the snow-capped Alps rise above the Lingotto building, and surge to the right, overlooking the actual cityscape below. You recognise characters collaged from film, fiction, newsreel, paintings, their contexts mashed up. Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin leads China’s “White Paper” protesters of 2022. In a student demonstration, Maria Callas as Medea marches with Gina Lollobrigida as the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio. There’s white-suited John Travolta from Saturday Night Fever, the humiliated father and son from Bicycle Thieves, Alice playing croquet with a flamingo.

It’s a wonderland, but strewn with trauma. The resolute figure of Jewish neurobiologist Rita Levi-Montalcini, who worked as a doctor in fascist Italy and survived to age 103, flanks a wheelchair-bound silhouette drawn by Turin artist Carol Rama, here pushed by Nietzsche as portrayed by Edvard Munch. “Walls sometimes speak” declares one slogan. There is all sorts of political graffiti; continually repeated are George Floyd’s final words, “I can’t breathe”.

“Pistarama” is a memorial for our times, an engrossing history of resistance and both inner and outward rebellion, and a fantastical musing on time and change. Unveiled in early May, it is also the monument which completes Lingotto’s own transformation, in exactly a century, from industrial powerhouse to stunning contemporary art venue.

As a post-industrial space (car production stopped here in the 1980s), the Pinacoteca Agnelli’s heft and style dwarf Tate Modern, while the roof has the scope of New York’s High Line. Live effects of sun, cloud, wind play across Gonzalez-Foerster’s sequences: fiery red backgrounds glow bright, then give way to wavy grey wastelands — appropriated from Tarkovsky’s Stalker — which in turn segue into the crumbling stone walls in Paris where Paul Moreau-Vauthier moulded ghostly faces to remember victims of the Commune, then to the translucent cliff paths, carved like sculpture, from Benozzo Gozzoli’s 1459 painting of the procession of kings in Florence’s Magi Chapel.

Foundations for Lingotto’s reinvention as a cultural icon were laid in 2002, when Renzo Piano constructed the top floor’s glassy space capsule to house the family’s collection — Canaletto, Canova, Modigliani, Italy’s best Matisses. But the new project is far more ambitious. In 2022 the roof became a sky garden — with 40,000 plants — and opened to visitors for the first time, and the Pinacoteca appointed a director, Sarah Cosulich, to programme Modern and contemporary exhibitions.

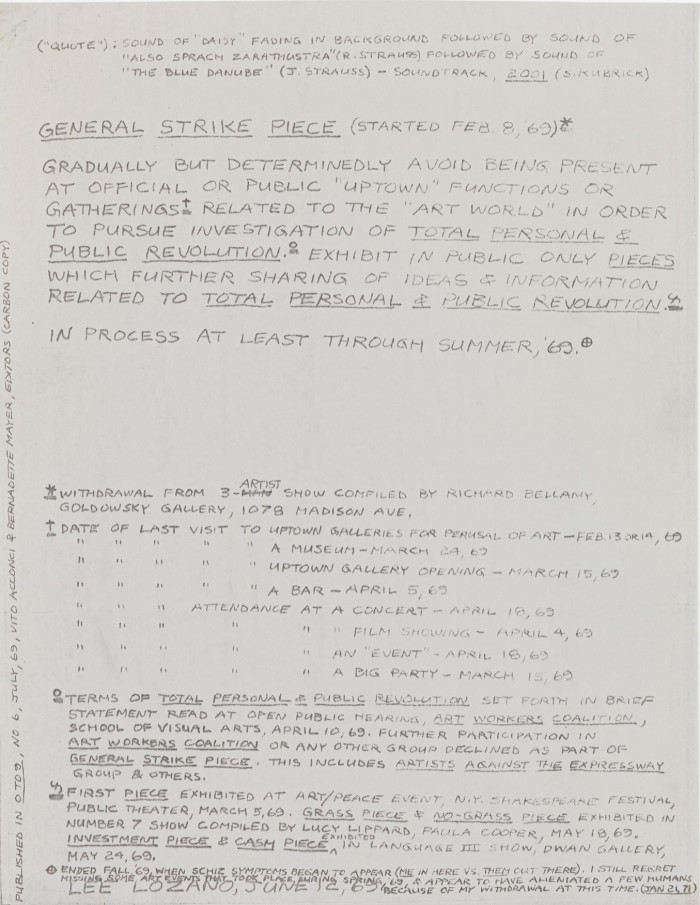

Her inspired double bill this spring pairs Lee Lozano: Strike, a rare retrospective of the American painter (1930-99), who used raucous mechanical imagery to violent, sexually explicit effect, with Gonzalez-Foerster’s imaginative exploration of protest. Gonzalez-Foerster’s starting point was stories of Lingotto’s anti-fascist workers in 1943 and strikers in 1968-69 — the moment Lozano began her “General Strike” piece, declaring withdrawal from the world. As a result, she is almost unknown today — yet revealed here as a strong, insightful artist.

Where Gonzalez-Foerster makes collective bodies a potent force, Lozano was an uncompromising individualist. Her show opens with charcoal self-portraits (1959): fierce features, clear eyes, mighty nose — the emphasis on protruding, pushing, continues throughout — yet in each drawing the boundaries between the outlines and the ground dissolve, as if she is already willing herself to disappear.

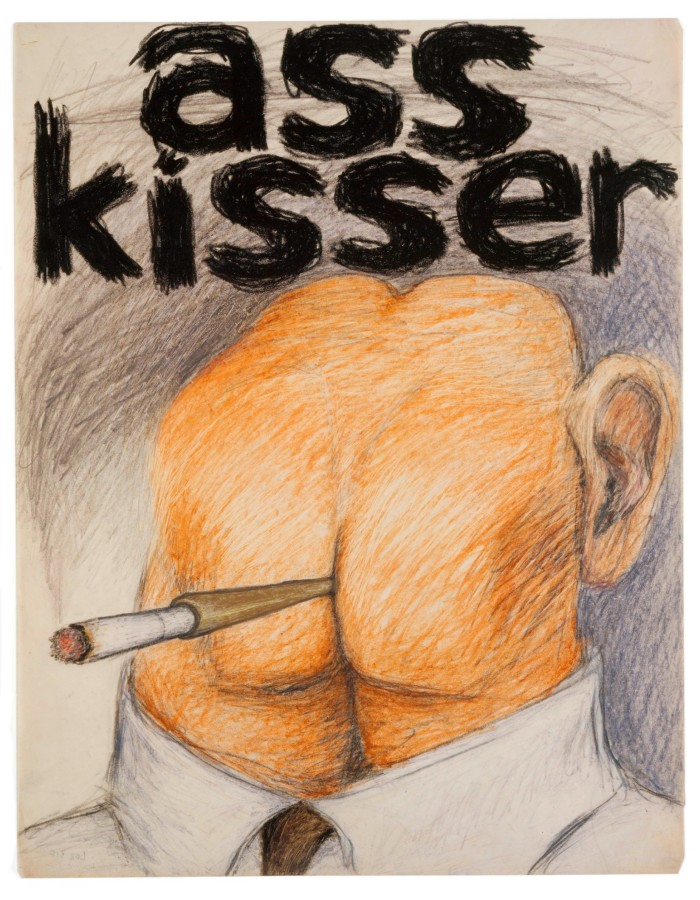

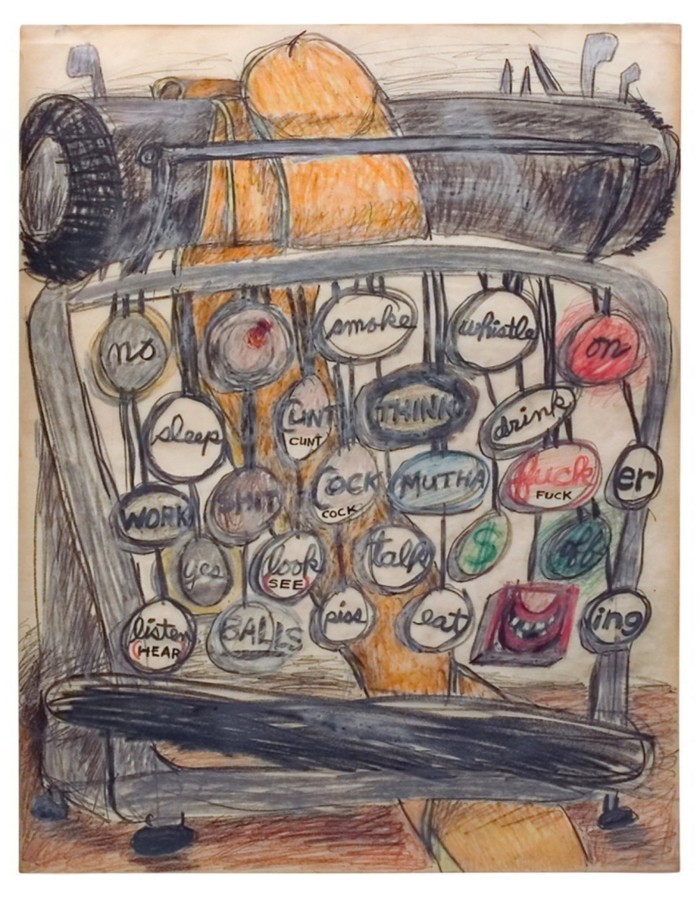

A metamorphosing energy gives the early works from 1962-64 angry humour. A phallus unravels into the paper in a typewriter (signifying women’s inferior status); its keys denote verbs — think, work, eat, piss, fuck — not letters. A businessman in suit and tie has his head turned into a rump — “ass kisser”. Lozano’s take on Courbet’s “Origin of the World” is a close up of a vulva as a black slot machine, a coin about to be inserted. A drawing of a saw is inscribed “he gave her a good screwing”. A gun ejects a penis, a spanner bursts from the fly of a pair of jeans, body parts sprout a lightbulb, an electric socket, and, above a row of penis tips, Lozano scrawls “finally cut them off”.

Her career lasted a decade, in which she hurtled from expressive gestural figuration, merging body fragments and mechanical objects, each animated and vibrant, to hard-edged abstraction in 1965-68. “Clamp” consists of two canvases whose long triangles taper to a point, clamped together along the diagonal where they meet. In “Cram” a darting red form pierces two grey columns, aggressively sexual, while “Crook” is a sinuous silver curve, its metallic sheen lusciously painted. All are enormous, fastidious paintings, and perhaps condensed what Lozano wanted to say about power and gender structures.

The Pinacoteca wisely excludes most of her subsequent conceptual word-pieces — narcissistic self-instructions about smoking grass, sexual and social behaviour. But the show is framed by the two which determined the rest of Lozano’s life: “General Strike”, promising to quit New York’s art circles, where she was achieving significant success, and “Dropout Piece” (1970). With “Boycott Piece” (1971) — a refusal to talk to almost all women — these marked her choice of obscurity and silence until her death in Texas; she is buried there in an unmarked grave.

How to understand Lozano? Some historians applaud her rejection of capitalism and patriarchy (blanking women, this argument goes, was feasible because they are powerless). I thought of the vanishing, absolutist heroine of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, and the Pinacoteca indeed offers intriguing contexts of metaphysical allusions.

Back on the ramp, Cosulich has commissioned works united by themes of mutability and disappearance. Echoing the rhythmic architecture of columns and beams, Cally Spooner’s beautiful stop-start cello piece “Dead Time”, based on a Bach prelude, is a meditation on emptiness — the ramp devoid of cars — and “possible modes of withdrawal”. “The hopes and dreams of the workers as they wandered home from the bar” (2005-22), Liam Gillick’s sprinkled red-glitter floor sculpture, shifts shape as visitors leave footprints or signatures, each erased by the next. From here you emerge into sunlight and Mark Leckey’s stadium-scale screen of computer-altered images of the surrounding mountains, melting, unstable, disorienting.

It is called “Beneath My Feet Begins to Crumble” and it’s at once a bleak warning about climate change and a happy reference to Lingotto, whose concrete and clay have survived, mutated and triumphed to become one of Europe’s most alluring cultural spaces.

‘Lee Lozano: Strike’ runs to July 23 in Turin, pinacoteca-agnelli.it, then at the Bourse du Commerce, Paris, September 20-February 12 2024

Comments