Collector Shane Akeroyd: ‘We are in a place of transition, a period of uncertainty’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I don’t say no very much and I don’t sleep enough,” explains the collector Shane Akeroyd, when I ask how he manages to combine an international banking career and parenting with a voracious appetite for contemporary art. Such restless enthusiasm has spawned a collection of more than 1,500 works, plus a fine library of rare books, built over more than 20 years.

Under the radar for most of that time, Akeroyd, who spent 22 years in trading rooms around the world including at RBC Capital Markets in New York and IHS Markit in Asia, seems to be everywhere this week. He has recently finalised a major donation to Tate — a six-figure sum to support the museum’s acquisitions of contemporary British art over the next five years — while on June 8 he launched his collection of 200 pieces of video art online, with publicly available programmes which change every six weeks.

Akeroyd also provided funds for Lydia Ourahmane’s oil barrels, recently unveiled in the Tate Britain rehang, and in Basel he is supporting the Kunsthalle’s exhibition of the British film and performance artist P Staff. This is all while continuing his 10-year backing of the associate curator role at the British Pavilion in the Venice Biennale. His board and committee memberships include at Para Site and M+ in Hong Kong, where he is now primarily based, Artists Space in New York and Chisenhale Gallery in London.

Akeroyd buys art with a similar intensity. While some collectors are happy simply to own objects, he places great store on knowing the artists he buys, many of whom — including Sarah Lucas and Jeremy Deller — he counts among his close friends. When we meet in London in the early afternoon, he has already had a coffee with a gallerist and bought a painting by Ravelle Pillay from Goodman Gallery that morning. “There isn’t a day in the week when I don’t talk about art,” he says.

The gallerist Sadie Coles — another friend as well as something of a mentor — says that “he is open to complicated, conceptual ideas and likes supporting the production of difficult work. His motives are genuine and his patronage is real.” Polly Staple, Tate’s director of collection for British art — and, yes, another friend — describes Akeroyd as “an ally who can make change happen”.

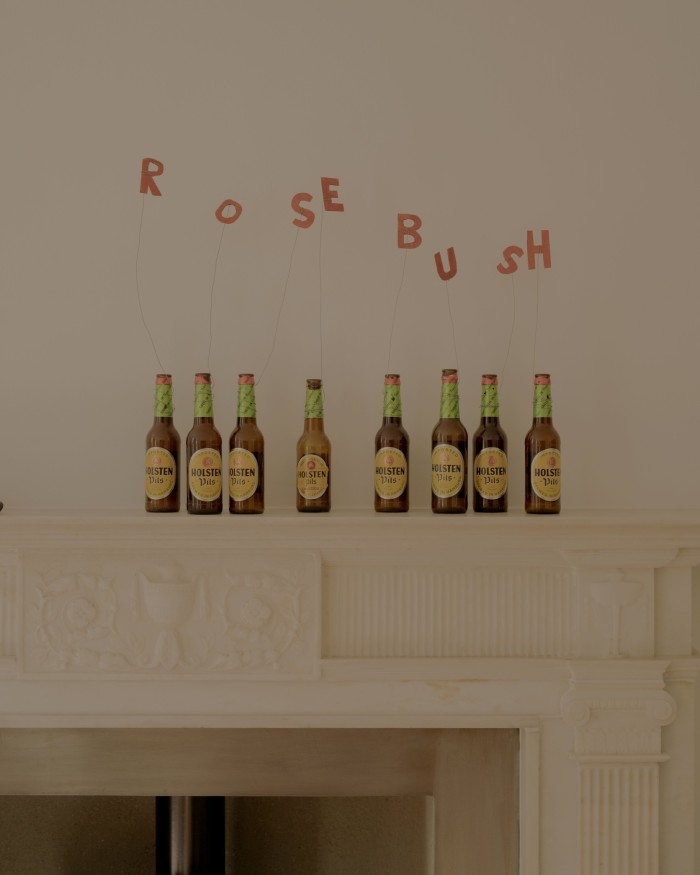

Akeroyd wears such praise lightly and has an unpretentious, self-deprecating patter. At his London home, he explains that “my attempt at curating is to have mostly British artists in London and artists from Asia in Hong Kong.” It is not a hard-and-fast rule, but Akeroyd does have several Young British Artists on show — including Lucas and an early surgical cabinet by Damien Hirst. More contemporary artists include Veronica Ryan, Denzil Forrester and Alvaro Barrington.

Now 58, Akeroyd smiles when I ask if he was brought up in an artistic environment. “I grew up with a young, working-class, single mum in Dover,” he says. He never knew his Pakistan-born father, though says his heritage gave him an “inbuilt sense of diversity growing up”. There must also have been something in the Kent water — his brother, to whom he is close, is Jonathan Akeroyd, chief executive of Burberry. “We didn’t have the internet, we didn’t have information about art or anything. Our route into culture was to read magazines and listen to records or read books that our heroes liked. That’s how we opened our minds.”

Through friends at university in London, where he studied economics, Akeroyd met Paul Stolper, now a gallerist specialising in contemporary prints. “Paul’s father was a [rare books] dealer. None of us had any money and his incredibly generous parents had us all over and fed us, and there was beautiful art lying around,” he says. Stolper proved “instrumental to my collecting”, indeed Akeroyd still buys from him — including, recently, works by the musician and artist Brian Eno, a reflection of the collector’s parallel cultural pleasures.

Akeroyd, who now applies his sales skills to investing and advising a range of companies, mostly in the tech and finance industries, is thoughtful about his own role within the art world, nearly a quarter of a century after he started out. “As you get older, you need to focus a bit. I don’t like to use the word ‘legacy’ but I have been thinking about how you bring it all together, how you can do a smaller number of more important things,” he says.

Opening his moving image collection to the public is, he says, “about community versus vanity” at a time when the more popular route for collectors has been a bricks and mortar private museum. The latest Tate donation “crept up on me”, he says, after several years of supporting the institution in other ways, partly through the “very persuasive” Staple and Maria Balshaw, director of the museums.

He is aware that the macroeconomic environment has changed since he started out. “The art market has been a reflection of cheap money creating oversupply [of art]. Now we are in a place of transition, a period of uncertainty, and things will cool first but the best-case scenario is that it will stabilise soon,” he says. For him personally it is a time “to keep my head down and focus on doing the next right thing” — which seems to suit the wider art world very well.

Comments