How does the US-China trade war hurt carmakers?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Brands are intangible assets but that does not make them immune from trade conflicts involving physical goods.

To thrive, brands need to make themselves indispensable, suggests Elspeth Chueng, global director of the brand equity database BrandZ: “It’s not just about the product, but what consumers need in their daily lives.” As prices rise to compensate for higher tariffs — $200bn imposed by the US and $60bn by China in May — brands will need to justify that extra money.

Just take US car companies in China, which are feeling the strain already. Sales in China have dropped for the first time since 1990, partly as a result of trade war uncertainty prompting consumers to hold back on purchases. Cars dropped from being the third most valuable exported good to China from the US at over $10bn in 2017, to fourth at $6.65bn in 2018, according to US Census trade data.

Ford has seen a decline in sales in China and has since dropped off the list of top 100 most valuable global brands. Luxury car brands, such as Mercedes-Benz, which has its biggest market in China at 28 per cent of its total unit sales, are seeing a slowdown in growth.

It is premature to forecast the demise of these companies on the basis of higher tariffs alone, however. “There have been a lot of tariffs on auto parts and components but nobody can find it in pricing anywhere,” says Scott Miller, senior adviser at the Centre for Strategic International Studies in Washington. Instead, Miller identifies economic nationalism as a more impactful risk: “I would never underestimate the power of nationalism in China”.

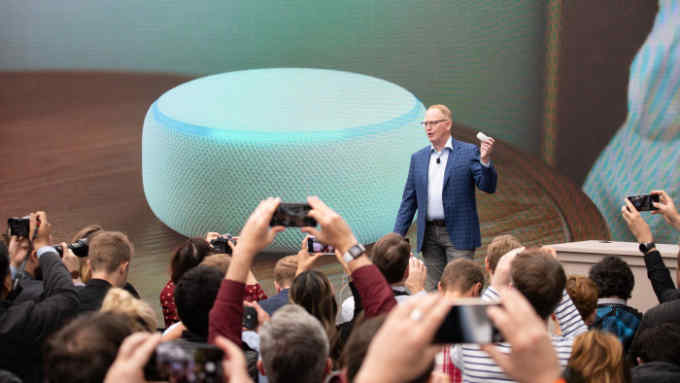

The carmakers are not alone in their struggle over China. US companies including Uber and Amazon have previously tried and failed to enter the market, unable to compete with their Chinese counterparts. Amazon’s market share fell to one per cent this year and they have since withdrawn from the country. If the Chinese government encourages consumers there to boycott US companies, on top of competing with better-known Chinese rivals, this could make it considerably harder for American brands to establish themselves.

The Chinese government at both national and local levels could increase inspections and delay processing applications, alongside other petty enforcement measures, according to Miller. On June 6, after the Trump administration blacklisted Huawei, citing it as a ‘national security threat’, China fined the Changan Ford car company over antitrust violations — a possible retaliation.

“It is the most worrying possibility. Chinese consumers tend to be quite patriotic,” says Cheung. While short-term harm to American brand value in China as a result of the trade war is difficult to gauge, it is certain that economic nationalism would make a big dent in both sales and reputation of brands in the long-term. In 2016 and 2017, China effectively boycotted South Korean goods as a result of the nation agreeing to deploy a US missile shield. The precedent is there, as is the potential risk.

As of yet full-on retaliation from China is only a possibility. Craig Allen, president of the US China Business Council, is unperturbed: “If anything, the Chinese government seems to be trying to tamp down on nationalism rather than exacerbate the nascent anti-Americanism,” he says.

Brands are expressing their concern on the other side of the fence: it will not take long for higher tariffs to cost companies, and consequently consumers, in the US as well. Since the Trump administration has increased tariffs on more than $200bn of goods on May 10, more companies have warned that higher prices adjusted to higher cost will deter consumers. Shortly thereafter, major US footwear companies wrote an open letter to Mr Trump requesting that footwear be removed from the Section 301 list published by the United States Trade Representative.

According to the letter, adding the proposed 25 per cent tariff could burden some US families with a 100 per cent duty on shoes.

The New York Federal Reserve found that the tariff increases could cost the average US household over $800 a year. “In the US, it will be more visible with consumer-facing goods such as apparel, footwear, luggage and consumer electrics,” says Miller.

So far, the general consensus seems to be that the impact has been contained. But if events continue along the same trajectory, companies will have to adapt to rising costs, prices and increasingly hostile attitudes internationally.

The question that Chueng poses for brands under pressure from higher tariffs: “How are you going to offer more to the consumers so the price increase is justified?”

Comments