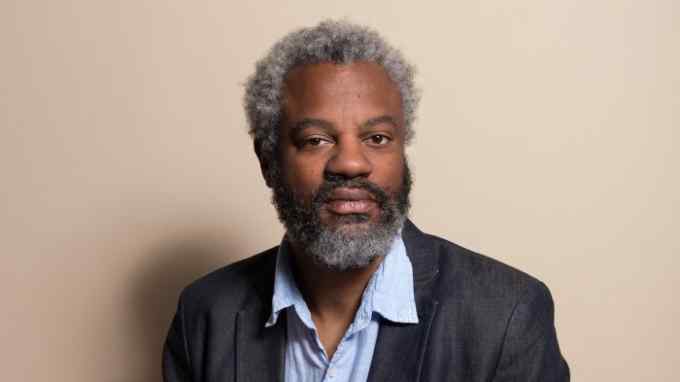

Film-maker Jenn Nkiru’s brain-bending vision

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I call it cosmic archaeology,” says Jenn Nkiru. In an editing studio in central London the filmmaker — dressed in head-to-toe galaxy purple — is taking a break from a marathon editing session to talk about how she makes her brain-bending shorts.

The archaeology reference is the easier part to unpack. In her films Nkiru, 32, creates densely stratified tableaux: archival footage and historical references to black culture are sardined with original scenes shot by Nkiru and her enormous team. Watching one of her shorts — En Vogue (2014), Rebirth is Necessary (2017) or Black to Techno (premiering this week in Los Angeles as part of the Frieze and Gucci “Second Summer of Love” series) — feels like falling down a Wikipedia rabbit hole, clicking through connected links until you forget where you began. Or, as Nkiru describes her vision for Black to Techno: “Imagine if you had 17 public access TV stations . . . and this person is just switching through these different things.”

And “cosmic”? Nkiru’s first commissioned film (aged 15, made with the BBC and Tate) told the story of an alien dropped on earth. From there, she developed an interest in all things tinged with the supernatural, from Afrofuturism to her own complicated theory that human memory might be some sort of cosmic energy. Without skipping a beat, Nkiru slips from talking about extraterrestrial others to political ones: people who are forced to migrate, who are made to feel they don’t belong.

Hers is an associative, superfluid way of thinking. “I’m trying to bridge the academy, pop culture and art,” she explains. She reads journal articles on cultural theory, and then tries to answer the question: “What would the visual embodiment of this theory look like if I was to apply it to black life?”

Nkiru is assured in her vision. So assured that, she says, she has been known to sit in the editing suite, close her eyes and simply dictate to her editor how she pictures a sequence unfolding.

She learned that confidence young. As she grew up in Peckham, south London, her father was studying for a PhD on the north-south divide in Nigerian politics. He ran the household as an informal salon. “I was always asked my opinion,” Nkiru recalls. “From a really early age my dad was very much like, ‘You have to have an opinion about something.’ ”

But her childhood wasn’t ruled by this intellectual heavy lifting. At the tail end of the MTV generation, Nkiru spent her weekends watching music videos, sometimes slipping into the audience of Total Request Live and CD:UK studio shows. She loved Missy Elliott, and the work of her frequent collaborator, director Hype Williams. For her, these three-minute slices of experimental image-making were a revelation: “I was like, ‘Oh my god. [Williams] is making videos like he’s making cinema.’ ”

Today, music videos are Nkiru’s bread and butter. She’s directed for the American jazz instrumentalist Kamasi Washington and Swedish pop doyenne Neneh Cherry, and last year swung on the coat-tails of the most powerful image-maker in pop when she was hired as second unit director on Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s video for “Apeshit”.

“What music videos allow you to do in a really short space of time is gather all this knowledge,” she says. “I’ll never forget something [film-maker] Mark Romanek said — ‘They allow you to test out ideas on someone else’s dime.’ ”

The work of all good conceptual artists seems opaque until you crack its code. With Nkiru, the thing to understand is that it’s the form of her videos, as much as their content, that makes her depiction of black culture so radical. For example, last autumn she created a video for Kamasi Washington’s “Hub-Tones” in which three women stand in front of a pan-African flag and sway hypnotically for nine minutes straight. Nkiru is making a point through the sheer length of the video. “I was reclaiming my time and my space. If you see a black person on screen, they have to be doing something. You can’t just stand there. ‘Dance!’ ‘Move!’ ‘Show me you can do something!’ Very often in cinema you can see a white man pondering . . . he has the grace of space.”

Similarly, Nkiru’s personal films intentionally never take a linear approach to narrative. By playing hopscotch with western notions of time and space, she is making a point: “Past can be present, present can be past . . . My grandmother [who is Nigerian] believes I am her mother, she calls me Mama.”

Nkiru describes what she’s trying to do with this formal experimentation as “cinema”. Whereas black “film” is interested in straightforward questions of representation — showing black lives on screen — cinema “bakes what you’re trying to say into the process”.

Black to Techno centres on the origins of techno music in Detroit’s black community in the 1980s. Of course, it has ended up being about a lot more than that: Nkiru is interested in the idea of mimesis, and researching techno — which was inspired by the soundscapes of industrial production lines — led her to consider how many earlier forms of black music, such as the blues and jazz, were infused with the sounds of their makers’ work environments.

Given that America is where the majority of her work gets commissioned, why does Nkiru choose still to live in Peckham? “That’s a good question,” she says, raising her eyebrows. Her decision to return to London (Nkiru studied film directing at Howard University in Washington DC) was motivated by the belief that the black British experience was comparatively underexplored. But she says she’s finding that opportunities to do that exploring are limited. “UK artists are not saying to me, ‘Hey, could you direct a video?’ ”

Some day, she says, she’d like to make a TV series about London — something that was “staunchly multiculturally British” — but even that might be more likely to happen stateside. She’d want to be an American-style showrunner (“In British TV, the writer is god, not the director”), and her reference point for the sort of show she’d like to create is also American: Donald Glover’s comedy-drama Atlanta.

The work Nkiru makes isn’t easy, and she doesn’t want it to be. “I don’t have a particular concern to be the type of artist whereby people like what I’m doing immediately,” she says. “I’d love it if someone loves my work today and they love it in 20 years but if I had to choose one, I’d be like, ‘I hope people are referencing it in 20 years as opposed to really just enjoying it for now.’ ”

‘Black to Techno’ premieres at Frieze Los Angeles on February 14

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments