Inside one of East Hampton’s most mysterious mansions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As far as “only-in-America” stories go, this is one for the centuries. It’s an epic tale with a global cast ranging from England’s Charles I – executed for treason in 1649 – to the last Shah of Iran, who was deposed by fundamentalist clerics more than three centuries later. Supporting these imperial cameos is a founding family of New York’s fabled Hamptons enclave – along with a dashing Jewish refugee whose good taste is helping to preserve one of the most historic properties on Long Island’s exclusive east end.

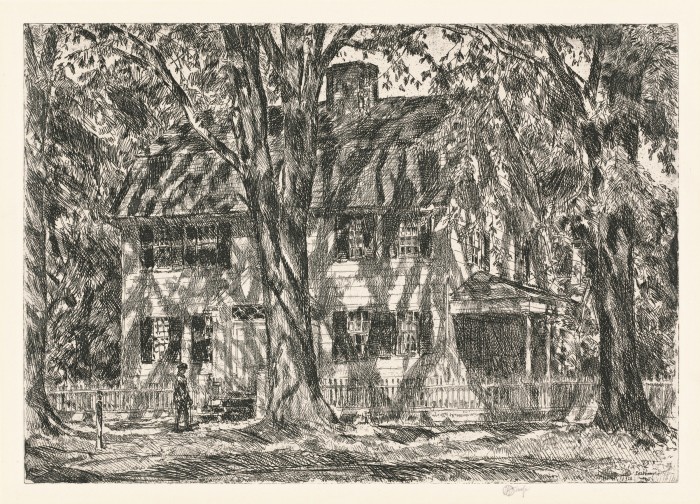

At the centre of this tale is, of course, a home: the Gardiner Estate – a hedge-shrouded, five-acre haven hiding in plain sight in the village of East Hampton. It claims Robert Downey Jr as a neighbour, but most folks would hardly know the estate is even there. Sprawling compounds are common in this billionaire’s playground some 100 miles east of Manhattan. But they’re typically found atop former potato farms, rather than rambling for acres just off Main Street.

The estate – and the Gardiner name – are as old as the town itself. The land dates back to 1648, claimed by the English-born paterfamilias Lion Gardiner, who arrived in 1635 and established the first English settlement in New York state a few years later. Within two decades Gardiner had accumulated more than 90,000 acres of land – much of it acquired from local Montaukett chief Wyandaneuch as appreciation for rescuing his daughter, kidnapped by a rival Indian tribe in what is now Rhode Island.

The most famous parcel is Gardiner’s Island, a 3,300-acre thickly forested island set in, yes, Gardiner’s Bay, 10 miles from East Hampton. The island, which was granted to the Gardiners by royal decree from King Charles I, is where Captain Kidd famously buried the bounty back in 1699. Today, it remains within family hands, entirely private and exceedingly off-limits from outsiders.

For more than 350 years, like Gardiner’s Island, the East Hampton estate was continuously owned by a descendent of Lion Gardiner. Its final Gardiner – Robert David Lion Gardiner – was a childless former Wall Street executive who inhabited the home until his death in 2004 at the age of 93. He was also half-owner of Gardiner’s Island, earning him the sobriquet “Lord of his Own Island” in his New York Times obituary. Upon his passing, the island became – and remains – property of his estranged niece, Alexandra Creel Goelet, with whom he repeatedly tussled in court. But with no direct descendants, the estate stood in a state of decrepit isolation until the arrival of Shahab Karmely, a Tehran-born Jewish refugee who fled for America amid the rise of the Ayatollahs in 1978. Karmely – who studied business at New York University and history of fine arts at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London – has built a sizeable real-estate development empire in New York and Miami. He came upon the Gardiner estate almost by chance. He’d rented and owned in nearby Southampton for years when a business contact suggested Karmely tour the property as a potential investment.

“The place looked totally haunted; the grounds felt like a graveyard,” recalls Karmely of the property, which is hidden by towering thickets of mature arborvitae trees. “Sort of like ‘Grey Gardens’, but without all of the raccoons,” he added humorously, referring to the iconic East Hampton home famously owned by eccentric relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. But despite the neglect, Karmely became smitten with the 12-bedroom, eight-and-a-half-bathroom, terracotta tile-topped Renaissance-style villa. He was also, he admits, heavily intrigued: “The whole story just felt so odd,” he says. “I’d driven past Main Street many, many times; who knew there was a five-acre estate hidden back there connected to this legendary family?”

For most of its history, the estate was inhabited by a series of agricultural structures until the early 19th century when, in 1835, the Gardiners erected a wooden home that served the clan for a full century. It also served, briefly, as the “Summer White House” when President John Tyler – who’d married a Gardiner in 1844 – escaped from the stifling heat of Washington for the relative chill of East Hampton. While clearly treasured, the home – along with its scores of prized fruit trees – was heavily damaged in the hurricane of 1938 that clobbered the East Coast from New Jersey to Quebec, claiming nearly 700 lives.

Barely a year later, the Gardiners were ready to rebuild – and commissioned the then-fashionable architecture firm Wyeth & King to devise a worthy replacement. The firm, which was founded in Palm Beach, is best known for conjuring many of the south Florida resort town’s most lavish piles. Its inimitable imprimatur can also be found in landmarks such as Shangri La, Doris Duke’s former home in Honolulu, now one of the world’s foremost Islamic art museums.

In East Hampton, the architects traded the region’s traditional wooden shingle-style construction for solid stone walls nearly two feet thick. “Built like a bunker,” is how Karmely describes the home, “but filled with technology that was cutting-edge for the time.” With its show-stopping entry foyer anchored by formal dining and living rooms, the property is reminiscent of those constructed for pioneering Hollywood cinema moguls on the great Beverly Hills estates of the same period.

Along with its sheer size, this history – unrivalled in layers and lore – immediately entranced Karmely, who as both a scholar and builder understood its rarity and potential. “Despite its being run down, I was amazed by the proportions of the home, the consideration given to how the interiors had been laid out,” he says. Karmely initially thought to buy the estate, subdivide it and keep a portion for himself. But as he learned more about the Gardiners, Karmely understood that this was a place that begged for stewardship and preservation. And so preserve it he has.

Working with his own crews, Karmely planned out a complex, four-year renovation that ultimately ended up taking twice as long (and costing many, many millions of dollars). The process was painstaking and sleuth-like, with hours spent sourcing and reviewing original photographs and floorplans – some found secreted in the home’s wine cellar, others acquired via the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. Karmley concedes he’s far “more of a builder than a preservationist”. But he understood the wisdom of retaining as much of the original estate as possible. After all, “they spared no detail in its design and construction”, he said. “It all just needed to be brought back to a fully functional state – I didn’t want to create something ‘Disney’.”

In practical terms, this meant adding or replacing “back-of-the-house” essentials such as a new elevator, geothermal heating and an elaborate security system – with 32 separate cameras. All of the home’s decorative window shutters and arched French doors were updated and refreshed, as were the bathrooms – now clad in heated, book-matched marble. A mahogany-lined screening room was also added on the uppermost level, while exterior walls were painted with period-specific hues from British company M&L Paints.

Meanwhile, inside, an Italian father-and-son team from Italy spent an entire year applying Venetian stucco and hand-run plaster mouldings throughout the interiors. “They lived in the staff apartment above the garage,” he says, “the effect is truly luminous.” Accented by custom-commissioned lighting from Best & Lloyd – established in Britain, in Birmingham in 1840 – the home also features an impressive collection of artwork ranging from 17th-century Dutch landscapes to newfangled NFTs.

Throughout the home, just a single wall was removed – scrapped to make space for a breakfast corner in the kitchen. “Everything else was left in place,” says Karmely, who notes that most of the home’s furniture is from George Smith and B&B Italia – accented by antique carpets from India and Iran including a Chinese art deco-styled showstopper exhibited by Milan’s Nilufar Gallery.

The estate gardens have also received a substantial – and much needed – upgrade. At its entrance, Karmely restored the original U-shaped hedges; just beyond, a handful of new fountains have been added. Extensive landscaping was undertaken in partnership with the landscape architecture firm Terrain – one of the many companies from Karmely’s professional black book he enlisted to work on the estate.

“I knew quite a bit about construction and historical references, but I knew next to nothing about gardening,” he says. “Every weekend for two years Terrain’s founding principal Steven Tupu drove from Manhattan to East Hampton to make sure we were progressing properly.” Today, Karmely’s gardens are lush and fragrant, overflowing with jasmine, rose organzas and clementines. “You’re completely bathed in scent out here,” he says.

The swimming pool was updated but retains its core DNA, while a pair of oversized, reflective, black-glass cubes designed by British artist David Harber were placed just beyond as futuristic pool houses. “They require endless maintenance,” Karmley says of the cubes, which were installed on-site by Harber himself. “But during the day they brilliantly reflect the trees and the sky, while at night they light up like lanterns.” Further on is the tennis court as well as the beginnings of an orangery.

Nearly two decades after first stumbling upon the Gardiner Estate – and nearly four centuries after its namesake helped establish the East End – Karmely along with his wife and two sons are now living in East Hampton full time. Karmely concedes that only a builder like himself – with decades of experience and the patience to weather the inevitable delays and overruns – would have had the cojones to take on a project of this magnitude.

“Even the billionaires and ‘money’s-no-object’ folks in the Hamptons would probably have been scared off by a project like this,” Karmely says. “I had a huge advantage because I’ve been building for decades,” he continues. “Because this is what I’m skilled at – this is what I do.”

Comments