Amber, the precious material that creates caskets and sea monsters

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Natural wonders have always fired the human imagination. Amber was no exception. For the ancients, this fossilised tree resin was a mysterious material washed up on distant shores. Sophocles and Ovid considered these small nuggets the hardened tears of grieving maidens; others, the dried sweat of the rays of the sun, secretions of the sperm whale or even the solidified urine of lynx.

Traded around the globe along so-called amber roads, it was valued as a precious material like no other — aromatic, translucent, hard yet easily workable into jewels and statuary, and ranging in colour from opaque white to a deep ruby red. It was thought to cure melancholy, toothache and epilepsy. That some ambers had inclusions — insects and animal and plant matter encased and preserved for eternity — made it a material of choice for tombs and memorials.

Amber as an art form will soon be under scrutiny at the Galerie Kugel in Paris. Its show, which opens next week, is the latest of the gallery’s imaginative exhibitions exploring lesser-known works, materials and techniques.

“Amber objects of exceptional quality and condition are extremely rare,” says fifth-generation dealer Alexis Kugel. “While amber has the same softness as ivory — and it is clear that some artists worked in both — amber is very rigid and easily breaks, almost like glass. We were fortunate enough to have a small nucleus of pieces from our father, but it has taken patience and time — more than two decades — to gather enough objects to offer a comprehensive view of the field.”

The gallery’s focus is what he describes as the greatest period of production — the late 16th to the late 18th century — when the world’s largest source of amber, the fossilised coniferous forests mostly under what is now the Baltic sea, belonged to Prussia. Here, amber was both a state monopoly and a favoured diplomatic gift — the most famous was the unimaginably extravagant Amber Room presented to Peter the Great of Russia in 1716. Subsequently looted by German troops in 1941, it was destroyed — or hidden — in 1945.

Another diplomatic gift to one of the most extraordinary patrons and collectors of all time, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, is not only the star of the show but, according to Kugel, “a piece beyond anything anyone has ever seen in terms of quality — in or out of a museum”. This architectural casket combines panels of opaque, milky and translucent amber with fine ivory carving and marquetry and engraved silver-gilt. Closer inspection reveals the amber panels are decorated with motifs of gold leaf engraved on the reverse, and with small ivory reliefs also placed under the amber. Even the unseen chambers containing the inkwells and drawers received the same lavish attention. Its virtuoso use of ivory to outline and enhance the amber elements, as in the technique of cloisonné enamel, has no parallel.

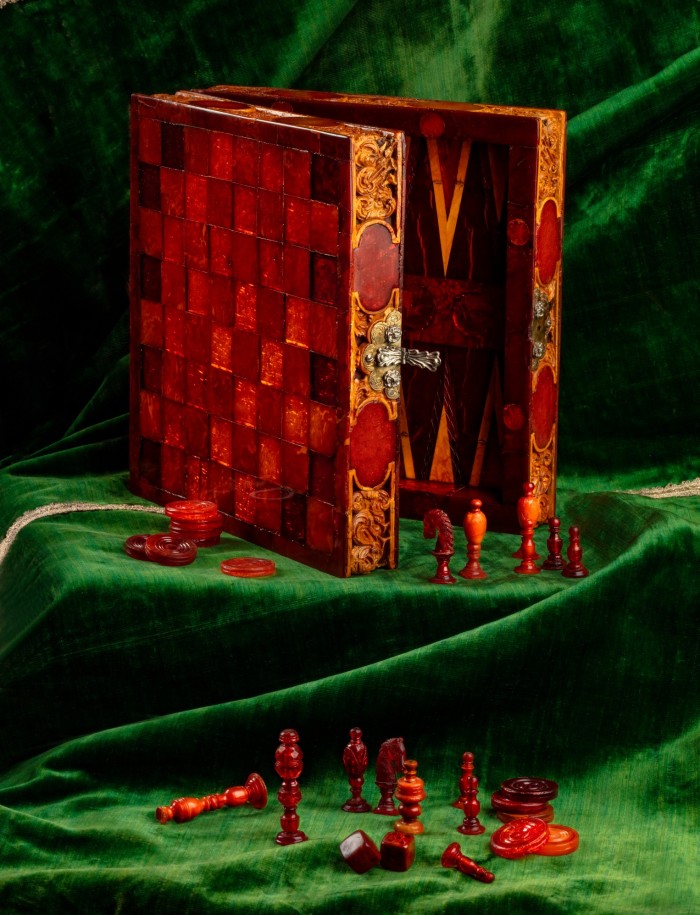

New archival research published in the exhibition’s scholarly and entertaining catalogue has prompted an attribution to Hans Klingenberg, whose only signed work is a backgammon board. He is revealed as the most important amber craftsman working for the Prussian ducal family in Königsberg — now Kaliningrad in Russia — around 1600. A hitherto uncatalogued games board by him here and the crucifix probably presented to Pope Paul V have also been added to the corpus of his works.

Amber craftsmen nimbly negotiated the sacred, the profane — fine art in the form of statuary and portrait medallions — and the utilitarian, if that is how one can justly describe the likes of the elegant, shagreen-cased knife and fork set with perfectly transparent amber handles here. Of the gilt-mounted objets de vertu such as needle-cases, perfume bottles and snuffboxes on show, the most extraordinary are those embellished with sumptuous jewelled and enamelled neo-renaissance mounts by Baron Alphonse de Rothschild around 1880.

Perhaps most beguiling, however, is the ugly and irreverent little sea monster confected out of a piece of raw amber with a crazed surface. The peculiarities of the amber must have suggested a turtle-like creature to its anonymous maker, who added sculpted polished fins and a head sticking out its tongue.

Kugel is inviting us to wonder at this little-considered material once more, plunging the gallery into darkness and dramatically illuminating the 51 objects spread across seven galleries. Elaborately carved amber vessels made without joints, such as the tankard attributed to Jacob Heise, glow as they reveal their carved menagerie of beasts and allegorical figures. Michel Redlin’s baroque tour de force of a two-tiered casket, ingeniously made without an inner wooden core, is as dazzling and resplendent as a stained-glass window.

“As far as I know, there is no such thing as an amber collector per se,” laughs Kugel, “and I have no idea who will buy these objects.” He is confident, however, that they will sell — like the tortoise-shell objects in their last exhibition — to first-time buyers in the field.

“When I organise an exhibition like this, I create a market.” Visitors buy with their eye. “The only question they need to ask is the price.” The answer is anything from a few thousand euros to several million.

October 18-December 16, galeriekugel.com

Comments