Giving hope: how to help ‘working poor’ US families build a home

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The poor must be meticulous. So Sherry Tilton writes down everything she spends.

How else can a single mother caring for a disabled daughter make a $12-an-hour job stretch to cover her monthly expenses — $620 in rent, a car payment, food, utilities and whatever else life throws at her? There is not enough money for health insurance, which Ms Tilton’s employer, a sign-making company in Tucson, Arizona, does not provide. So she goes without. She is not paid for holiday, so she goes without that, too.

The slightest gust of unanticipated news can blow her finances off-course entirely — like the $144 car registration fee she had overlooked a few months ago. “It just jumped on me — I should have known,” said Ms Tilton, 53. She has fine, platinum hair and flips easily between laughter and tears.

There is one other thing Ms Tilton faithfully records: the $50 or so she puts away each month, steady progress towards her dream of one day owning a home.

In September, she was accepted by a charity called Habitat for Humanity, which builds low-cost houses with people like Ms Tilton — the working poor who are just scraping by, yet are somehow deemed too well off for public housing. If the prize seems distant, it looms just across the street from Ms Tilton’s two-bedroom flat at the Tucson Palms apartment complex — a glamorous-sounding facility whose namesake trees are withered and whose railings have been appropriated as clothes lines. There, on the other side of Yavapai Road, the wooden frames of nine new Habitat houses are rising on concrete slabs that have taken over a vacant lot.

“I prayed for a house — not a house, exactly. But a place where I could be secure,” Ms Tilton said. The possibility is almost unimaginable for a woman whose parents had both died by the time she turned nine, sending her into a succession of foster homes, runaway attempts, and then teenage pregnancies.

“It’s such a blessing for someone like me,” she said. “Without Habitat, I’d pretty much die homeless.”

Building stability

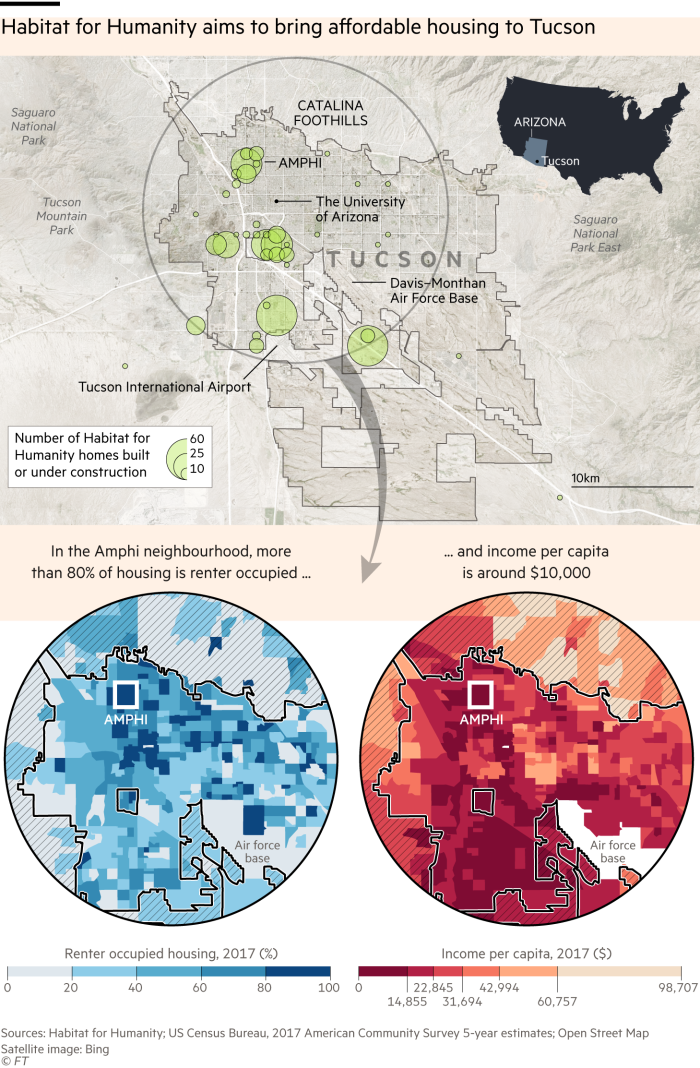

In Tucson, Habitat is attempting to do on a large scale what it is doing for Ms Tilton and her daughter: not merely provide shelter but bring stability to people and places plagued by transience and upheaval. There is plenty of need.

An hour north of the US-Mexico border and set against the southernmost foothills of the Rocky Mountains, Tucson is a blend of paradise and poverty. Its desert landscape is otherworldly. Philip Green, the British retail mogul, recently took refuge from legal troubles back home at Tucson’s luxurious Canyon Ranch spa. Yet even though it has been transformed by bursts of growth in recent decades, the city’s Sun Belt economy still tends to feature a preponderance of low-wage, dead-end jobs. A study by the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think-tank, ranked it as one of the US’s 10 most deprived larger cities. Its location near the border means it has an abundance of first-generation immigrants.

The 2008 financial crisis was particularly brutal. At one point, the unemployment rate for the construction industry spiked to 42 per cent. The city only this year recovered the jobs lost during the deep recession that followed. “We got hit really hard,” said Jonathan Rothschild, a Democrat who was elected mayor in 2011. He still notices scars from the widespread home foreclosures when he walks Tucson’s streets. “You’ll see neighbourhoods where two or three houses are really nice and then one is a dump,” he said.

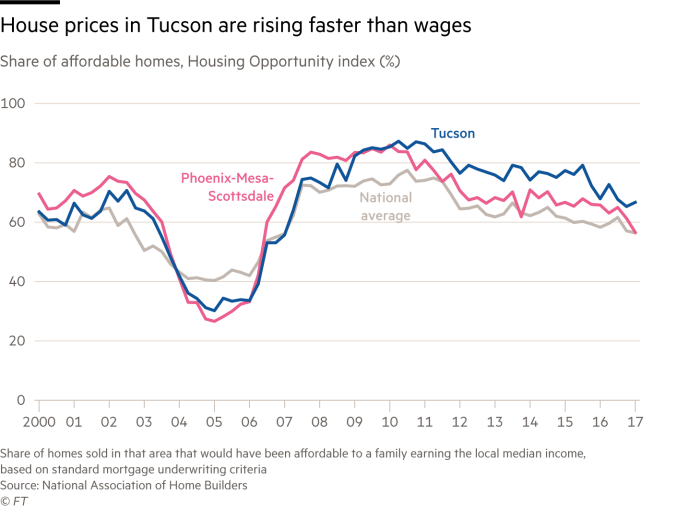

Developers have returned. Money is flooding in, for example, to build fancy student housing near the University of Arizona campus and high-end homes in the hills north of the city.

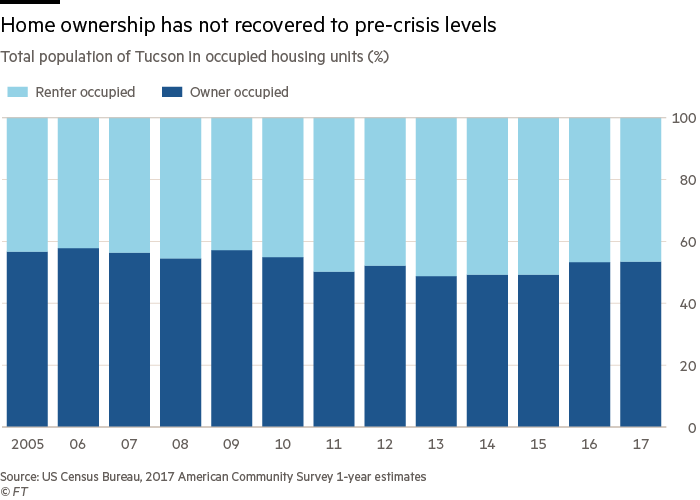

But no one seems to want to serve people like Ms Tilton. In fact, home ownership is lower than it was before the crisis in Tucson, with many people who lost their homes still renting — some in trailer parks and seedy roadside inns that have become warehouses of the working poor. “We have great need for affordable housing,” Mr Rothschild declared, calling homeowners “the glue of a community”.

Habitat is known for its hammer-swinging volunteers — most famously, former president Jimmy Carter — who have served more than 13m people since the charity was founded in 1976 in Georgia by Linda and Millard Fuller, a couple who gave up their wealth to pursue their Christian ideals. In the US last year the charity helped put up about 4,000 low-frills homes.

The Fullers’ idea was “partnership” housing, in which volunteers work together to build simple homes that are affordable but not free. Ms Tilton, for example, will have to contribute $2,500 as a downpayment, perform 250 hours of volunteer work — plus 50 for her daughter — and also complete a financial literacy course that will prepare her for home ownership. Her monthly mortgage payments, capped at 30 per cent of her income, won’t be very different from her current rent. But each time she makes one, she will be building equity in an asset of her own.

Habitat could build houses faster and cheaper if it just hired builders. That is not the point, though, according to T. VanHook, the Tucson chief executive, who argues that volunteer participation is part of building a movement to support Habitat’s larger goal of affordable housing. “People think we’re a housing organisation — we’re not,” she told me. “We’re a social justice organisation.”

The metric for success was once the number of new houses Habitat could put up, but that is no longer the case. Increasingly, it is taking a more holistic approach of trying to improve the health of fractured neighbourhoods. In Tucson, that shift began almost 20 years ago after local residents picketed Habitat, fearing it would dump undesirables in their area. Ms VanHook’s predecessor engaged the angry neighbours, to persuade them of the wider benefits Habitat could bring to the community.

“They want what everyone wants,” she said. “They want safe neighbourhoods, to feel like the people who move in will be invested in their community.” She is now trying to replicate that approach in Ms Tilton’s neighbourhood of Amphi, which happens to be one of Tucson’s poorest.

Community reborn

Amphi was once a tight-knit, working-class enclave where the local churches were pillars of the community. But in the 1980s, people began fleeing north to the new suburbs. By the late 1990s, a generation of homeowners had died off or deserted. These days, Amphi is almost 90 per cent renters. Some are recent arrivals from across the Mexican border. Others are refugees from the far corners of the earth who have been settled in Amphi by the government or aid groups because of its inexpensive housing. Many are gone within a matter of months.

Their attachment to the neighbourhood — or lack thereof — is evident. Amphi features abandoned cars, ragged chain-link fences and burglar bars. Drugs and prostitution are recurring problems.

On a recent afternoon, a Liberian man wearing a winter hat and sweatshirt in the midday heat wandered down the street, occasionally inspecting the rubbish. Nearby, a Sudanese woman sat alone in a dusty park, hands folded, seemingly wondering how she had ended up in Amphi. The place is so transient that at the local high school the annual turnover is a staggering 45 per cent. “You’re always getting your heart broken because you work with a kid and then find out they’re moving,” said Jon Lansa, the school’s principal.

Habitat’s arrival, even on a modest scale, has been cause for celebration. “When Habitat said, ‘we’re going to build houses,’ we said, ‘finally! Homeowners!” recalled Maureen Hazlett, who has lived in the neighbourhood since the 1960s. These days, she counts only five owners within a five-block stretch. “You have very few people you can count on to help you,” Ms Hazlett, who founded a local homeowners’ association, explained. “You can’t really build up a base to do things.”

After canvassing the neighbourhood, Habitat is building nine homes on a plot across from Ms Tilton that was, just a few months ago, an overgrown lot.

“I drive by every morning and I can see if they’re working or not,” she said, hoping that one of the houses might one day be hers. Habitat is also partnering with Literacy Connects, a local charity that refurbished a neighbouring church in Amphi that had become a venue for drug use and after-school fights. Together, they have planted a community garden. The hope, according to Susan Friese, Literacy Connects’ director of community engagement, is to seed community in ground that had been left to waste.

‘A home was my dream’

The Habitat building site and Literacy Connects are but a small patch in Amphi’s shabby sprawl. But, with sustained attention, and the help of city and state grants, Amphi might one day look a bit more like Copper Vista, a southern Tucson neighbourhood that features rows of tidy Habitat houses. Many of the residents know one another, not least because they have swung hammers side-by-side.

One is John Tabaruka, who lived in Amphi with his wife and six children when he arrived from a refugee camp in Zimbabwe after fleeing his native Congo. In 2013, after seven years of waiting, his application for a US visa was finally approved. “A week before they tell me: you’re going to America. Arizona… in Tucson,” he recalled. “You don’t know anything about it!”

Mr Tabaruka, 39, went to work as a maintenance man in one of Tucson’s trailer parks and lived in public housing in Amphi. “Everybody was like a stranger to everybody,” he said of the neighbourhood. Almost immediately, he and his wife began dreaming of a home of their own. In his case, the term “sweat equity” took on a rather literal meaning after the Tabarukas were accepted by Habitat in 2016. Because he could not afford to quit his maintenance job, he did his volunteer building for Habitat in Tucson’s broiling midday heat, when much of the city shuts down.

“You’re going to die!” he laughed, recalling a friend’s warning. He did not. And in May, the Tabarukas moved into a four-bedroom home. His monthly mortgage payment of $730 is manageable on his roughly $24,000 salary, he believes. He recently met a financial planner to discuss college savings accounts for his children.

Against the backdrop of a sulphurous national debate over immigration, exacerbated by the US midterm elections, the sight of Mr Tabaruka in his living room — king of his hard-won castle — was a restorative vision of an American dream. He was planted in an oversized leather couch with built-in drink holders while his twin boys, just home from the local school, giggled as they watched a video in the kitchen. Beside Mr Tabaruka was a flatscreen television roughly the size of a rooftop solar panel. Out front was a waist-high orange tree he had recently planted in the rocky soil.

“That was my dream — to get a house,” Mr Tabaruka said. “A home.”

Photographs by Norma Jean Gargasz

Graphics by Christopher Campbell

• Your gift will be doubled

If you donate to Habitat for Humanity through the FT’s Seasonal Appeal, the Hilti Foundation, a charitable organisation, has generously agreed to match your gift. Click here to donate now

Read more about our Seasonal Appeal partner Habitat for Humanity: ft.com/habitat-facts

Comments