Dubai’s Careem rides high after $3bn Uber buyout

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Given the Middle East’s longtime focus on the oil industry, it may be unsurprising that it was not until 2016 that the region produced its first “unicorn” — a tech group valued at $1bn or more.

By tapping into the region’s youthful, tech-savvy populations, Careem, a Dubai-based ride-hailing group, has become the poster child for the tech sector across the Middle East and north Africa.

Founded in 2012 — three years after US-based Uber — Careem competed against its international rival across the Gulf, north Africa and Pakistan, deploying local knowledge and innovative regional variations.

So successful was the regional challenge to Uber that in March this year the US group agreed to acquire Careem for $3.1bn in the region’s largest tech buyout. The deal is expected to close in January.

Careem, while poised to become a wholly-owned Uber subsidiary, will carry on operating under its own brand, led by Mudassir Sheikha, co-founder and chief executive.

The group has set its sights on becoming a one-stop shop application for a broader array of services as it expands into mass transportation and deliveries, with its payments platform binding its large customer base together.

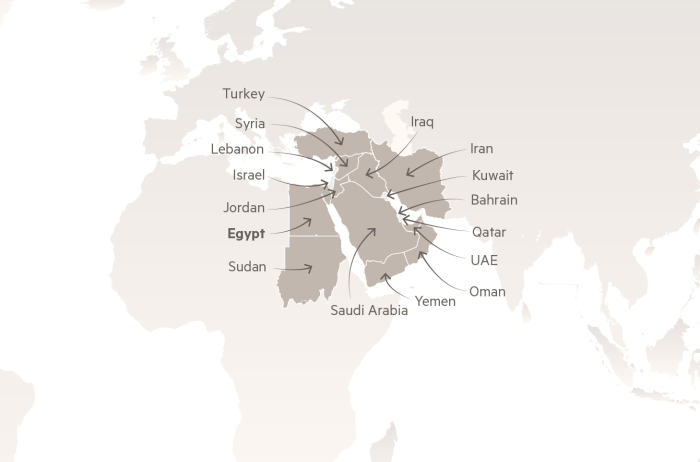

Operating in more than 100 cities across 14 countries, from Morocco to Pakistan, the group has more than 33m customers and can deploy more than 1.2m “captains”, as it dubs its drivers. As Uber said when announcing the acquisition: “This transaction brings together Uber’s global leadership and technical expertise with Careem’s regional technology infrastructure and proven ability to develop innovative local solutions.”

Revelling in its homegrown status, Careem has ventured into tough markets, such as Palestine and Iraq, where a dearth of quality infrastructure has opened opportunities for the company. “Innovation is at the heart of what we do at Careem and has been critical to our success in winning over local markets,” says Mr Sheikha.

From launch, it operated 24-hour call centres for Arabic and English, before introducing French, Turkish and Urdu options. Originally a corporate service, the group expanded into on-demand and scheduled bookings.

The company has moved beyond taxis into other areas of transportation, launching a bus service in Cairo and a Jeddah-Mecca route in Saudi Arabia for pilgrims.

Careem is also developing the “last mile” of transportation to expand its networks. It acquired a bike sharing company in the United Arab Emirates’ capital of Abu Dhabi this year and has plans to launch a similar scheme in Dubai.

Food delivery is being rolled out across the region, with pharmaceuticals and groceries to be added later this year and in early 2020. “Uber proved the model and Careem was able to compete quite effectively with Uber by being more nimble and by localising better,” says Rabih Khoury, a partner at Middle East Venture Partners, a regional venture capital group.

But like its erstwhile rival and prospective owner Uber, Careem’s growth has been hampered by regulatory resistance.

In the UAE, for example, some of its drivers faced official harassment, including being detained for operating without a licence. The groups later signed deals with the transport regulators that codified pricing arrangements, keeping fares above those of regular taxis operated by the government and influential local families.

Saudi Arabia, in the throes of social and economic change, has proved a fertile testing ground for ride-hailing apps. As the government seeks to divert nationals into the more productive private sector away from state jobs, around 515,000 people now earn an income through Careem’s platform in the kingdom, where 97 per cent of drivers are citizens.

“There was a large demand to improve the taxi service in the Middle East and north Africa, especially in Saudi Arabia, because of dirty old cars, unreliable service with language barriers and unqualified drivers,” says Mr Khoury.

An option to pay in cash — vital for the relatively unbanked Middle East — was rolled out in the kingdom in 2015. Expanding the use of its payment system to provide broader financial services is the next stage in Careem’s development strategy. Careem is seeking to widen the provision of financial services through mobile phones in a region where three-quarters of the population do not have a bank account.

The Middle East’s young population — 40 per cent are under 25 — has helped drive mobile phone ownership to about two-thirds overall, and up to three-quarters within the wealthier Gulf states.

With only 2 per cent of commerce occurring online in the Middle East, the company is one of many targeting what it sees as a $500bn consumer internet market opportunity.

Says Mr Sheikha: “As we move towards becoming the region’s everyday ‘super app’, innovation will play an even bigger role in providing the right services to simplify and improve more lives across our region — this will be key to Careem’s success.”

FT Future 25: Middle East

Supported by

Comments