Stock investors face up to tough reality of higher rates

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Equity specialists at some of the world’s largest asset managers are brushing up on their history and digging into new data sources to convince clients to keep investing in stocks in a world of higher interest rates.

After a decade of gains, the Federal Reserve’s historic series of interest rate rises in the last year has transformed the outlook for equities.

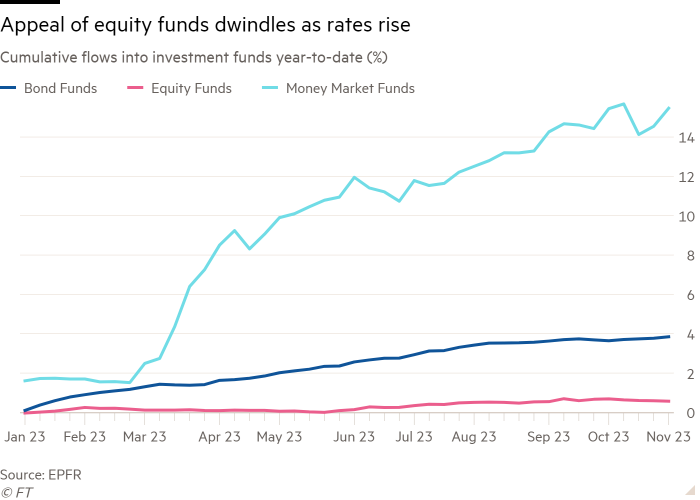

Pension funds and wealth managers are already investing less of their funds in stocks, attracted instead by the high interest on offer from money market funds and bond holdings. Net flows into equity funds have been practically flat so far this year, according to data from EPFR.

But specialist portfolio managers are keen to stress that there are still opportunities in the stock market — even if the years of broad gains driven by loose monetary policy are over.

“If you look back at history, it’s the post-[2008 financial crisis] period that is the anomaly,” said Tony Despirito, chief investment officer for fundamental equities at BlackRock.

“The equity risk premium — the relative reward of stocks versus bonds — was incredibly favourable. Now it’s back to long-term averages, but that is still quite good. That’s the perspective investors need.”

Higher interest rates reduce stock valuations by reducing the appeal of potential future earnings. If investors can earn a yield of almost 5 per cent on low-risk assets such as two-year US Treasuries, companies need to make a stronger argument to convince them to bet on long-term growth.

US stocks may have bounced recently on hopes that the Fed will not lift rates any further, but even if those hopes prove accurate, few are expecting a return to the prior period of easy money.

In their most recent forecasts in September, central bank officials projected the federal funds rate could still be as high as 4.9 per cent by the end of 2026. Even the minimum forecast of 2.4 per cent would be well above where it sat for most of the period between 2008 and 2022.

“For much of the past 15 years or so . . . we had the perfect cocktail for equities,” said David Donabedian, chief investment officer at CIBC Private Wealth Management. “This is different, and I think it’s going to be different for some time.”

Higher for longer

This is the fifth in a series of articles about the impact of high interest rates across businesses, governments and economies around the globe.

Part 1: Private equity takes a hit

Part 2: Government finances and the impact on markets

Part 3: Reverberations in the corporate world

Part 4: The consequences for emerging markets

Part 5: Implications for asset management

Eric Veiel, head of global equity at T Rowe Price, the $1.3tn fund manager, said the shift would impact both short- and long-term demand for stocks. In the short-term, he said, many investors would be tempted to “sit in really short-duration fixed income or cash and wait to see a few more cards flip over” given the uncertain economic climate. Longer term, assets such as high-yield bonds — which currently yield an average of about 9 per cent — have become an attractive alternative to stocks.

The recent performance of the S&P 500 highlights the tougher environment, but also shows how some companies can still generate big returns.

The index has risen 14 per cent year to date, but the gains have been driven almost entirely by a few large tech stocks. The majority of companies in the index have declined, and the version of the index that assigns equal weight to each individual company has dipped 1 per cent.

Amy Wu Silverman, an equity derivatives strategist at RBC Capital Markets, joked in a note last month that “it’s a rates world and equities are just living in it”. Research by Citi’s equity sales team last week noted that the US government’s quarterly auctions of 10- and 30-year Treasury notes — which are “not normally on the radar” for equity investors — had begun to have a bigger impact on stock markets than major economic data releases such as the monthly payrolls report.

Still, the outsized gains of companies such as Nvidia — whose shares have more than tripled thanks to enthusiasm about the potential of artificial intelligence — show that some stories have been able to cut through the noise around interest rates.

Sinead Colton Grant, BNY Mellon’s head of investor solutions, said: “Investor calibration has to change . . . it is perfectly possible to have portfolio allocations to equities that perform well in those environments, but you do need to be more selective.”

Along with AI, portfolio managers are trying to find winners and losers from other secular trends such as the emergence of weight-loss drugs like Ozempic, or the growth of “reshoring” production in response to geopolitical tensions and trade barriers.

They are also trying to distinguish between companies that will be directly affected by higher borrowing costs, and those that have been unfairly penalised in the rising rate environment. Veiel said he was looking for opportunities in sectors such as utilities and healthcare where indiscriminate selling had hit good companies as well as bad.

“Commoditised selling creates distortions . . . it doesn’t mean all the companies [in a sector] will be buys, but you want to go through and resharpen your pencil.”

Goldman Sachs’ basket of “high-quality” companies — US businesses with stable earnings and relatively low debt levels — has returned 17 per cent this year, compared with less than 1 per cent for its equivalent basket of highly indebted and less profitable groups.

Closely studying a company’s balance sheet and debt profile should not be a novel experience for an equity investor. But the extended period of low rates means that even relatively senior analysts and portfolio managers have never invested in a “normal” interest rate environment.

Veiel said investors needed to be wary that a stock may look cheap compared to valuations in the past but “we need to be making sure we frame our analysis not just versus the last five years”, said Veiel. “You can’t build a valuation premise on going back to lower rates.”

“We have folks who’ve been around 30-plus years, and we lean on them in these environments,” he added.

BlackRock’s Despirito agreed that “we’re in a market that either favours people with a lot of long-term experience, or at least students of the history of the market.”

Analysing a company’s debt and refinancing risks, he added, “is an easy financial exercise . . . but people don’t always pay attention. Indices definitely don’t”.

Comments