Greek bonds: the long way back towards investment grade status

Simply sign up to the Investments myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When investors queued in March to place nearly €12bn of bids for a new Greek sovereign bond, it marked a turnround for a country that is clawing its way back to financial respectability after three IMF bailouts in less than a decade. The sale saw Greece price a 10-year bond for the first time in nine years, raising €2.5bn.

After years of being a capital markets pariah — as a consequence of its role as the focal point of Europe’s debt crisis that kicked off in 2009 — Greece is edging back towards international respectability.

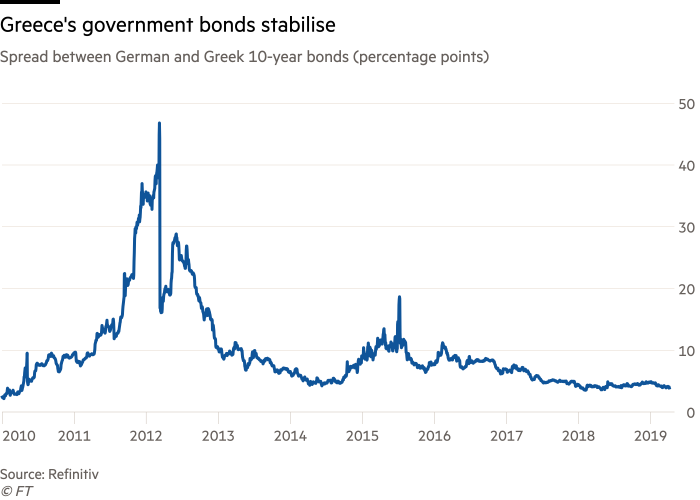

Its 10-year bond yield has fallen 1 percentage point since it graduated from its third bailout in mid-2018, to 3.3 per cent — having reached 40 per cent at the height of the eurozone turmoil. Bond yields fall when their prices rise, with higher yields reflecting greater uncertainty.

The spread between the Greek 10-year bond and its German counterpart — a widely watched indicator of eurozone political tension — has dropped 70 basis points to 3.3 per cent, with German Bund’s 10-year yield hovering around 0 per cent.

“It’s unquestionable that Greece has made a lot of progress,” says Andrey Kuznetsov, senior portfolio manager at Hermes Investment Management, citing the country’s improving “current account fiscal trajectory and debt burden”.

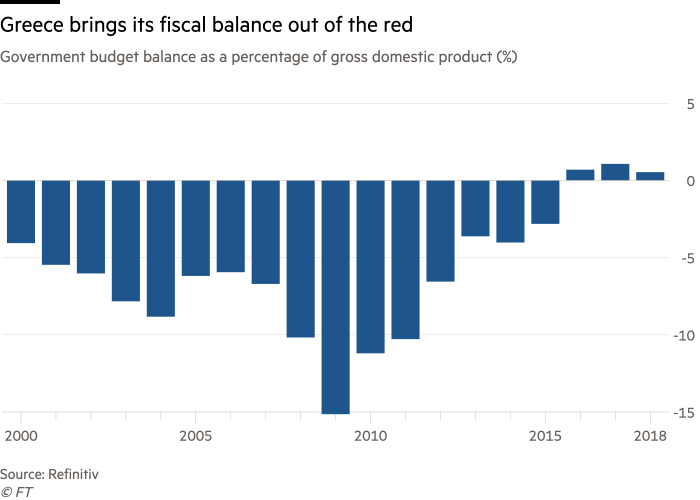

The IMF expects Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio to fall this year to 176 per cent, having peaked in 2018 at 188 per cent. Meanwhile, the country’s efforts to tackle public spending have paid off, generating record budget surpluses.

The economic improvement is helping to salvage Greece’s credit rating, which bottomed out in 2015 and has been clawing its way back towards investment grade. Though still firmly in junk territory, Greece was upgraded again by rating agency Moody’s in March.

Greece’s debt market has also been buoyed by the eurozone’s wider economic conditions, which have fuelled a general fall in yields across the bloc.

“It’s a positive economic environment for spreads in general, so people are looking for the highest-yielding assets possible, and in the government bond market that’s Greece,” says Seamus Mac Gorain, a portfolio manager at JPMorgan Asset Management.

There is still more to do, however. Investors are watching the forthcoming elections, due by October at the latest, which they say could be an opportunity.

“Typically investors don’t really like elections, but in this case you have a choice between this government, which has delivered on expectations, or the opposition, which is more business-friendly, so we are looking at potential upside rather than potential downside,” says Mac Gorain.

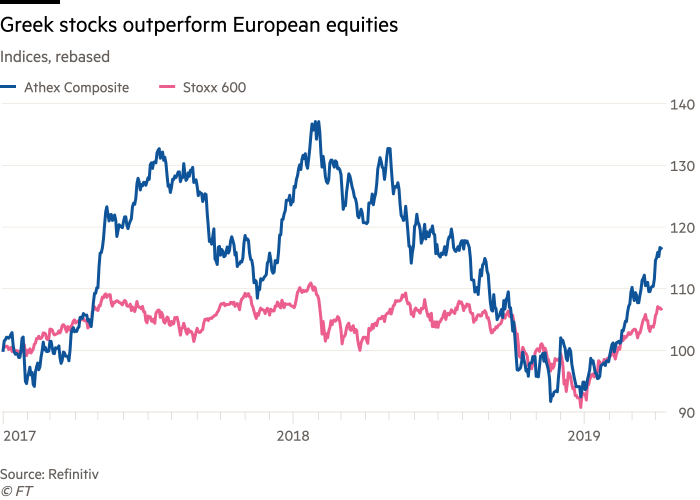

Another factor for investors is Greece’s progress in dealing with its banking sector. Greek bank stocks have outperformed the eurozone average recently: the FTSE Athex banks index is up 4.7 per cent since Greece completed its third IMF bailout last summer, compared with a 1.7 per cent rise across the Euro Stoxx banks index.

“Non-performing loan ratios in the banking system are still high,” says Kuznetsov. “Greece needs to change its bankruptcy laws to make it easier for banks to repossess, but it won’t address that until after the elections.”

Perhaps the most vital factor for Greece’s credit rating is its access to capital markets — and that, rather than a need to raise fresh funds, is the reason it has pressed ahead with bond sales.

The bailouts left Greece owing more than three-quarters of its national debt to public bodies such as the European Stability Mechanism, the eurozone bailout fund. Those debts are long-dated, with the bulk maturing from the mid-2020s onwards, which alleviates Greece’s immediate financing needs.

“Market access is most important for rating agencies,” says Mac Gorain. “The point at which Greece took a hit to its credit ratings was when it lost market access, so rebuilding that is very important.”

However, even the most optimistic investors acknowledge that they will need considerable patience in the coming years.

“It’s still a long way back,” says Mac Gorain. “Our central case is that the economy and credit ratings will continue to improve, but debt-to-GDP is so high and growth relatively slow that it will take a long time.”

The “terrifying bungee-jump” recession that Greece experienced “really degraded the fabric of society and discouraged businesses and individuals from making investments in the economy”, says Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist at fund manager PGIM Fixed Income.

“As a result, the recovery has been slow — it’s been an arduous grind towards positive growth and [in future] it’s going to be contingent on them not alienating investors [further].” Tipp is a Greek debt holder but acknowledges it is “a super-contrarian trade”.

Greece’s position as a developed-market sovereign with a junk credit rating means it does not qualify for inclusion in major bond indices — a big influence on how investors allocate capital.

“If Greece continues to make [economic] progress, it is going to go back into the world of index investing, but that could take two to five years,” says Tipp. “Over that time [Greek spreads] are going to remain wide relative to their fundamentals while they try to regain the credit rating notches they need to reach investment grade.”

That means investors in Greek bonds will benefit as the country grinds its way back towards investment grade status, but slowly.

“That massive spread over core eurozone bonds is likely to be there for a very long time,” says Tipp. “For bond investors this is going to be the gift that keeps on giving.”

Comments