Big Tech jockeys for position in scramble for health data primacy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

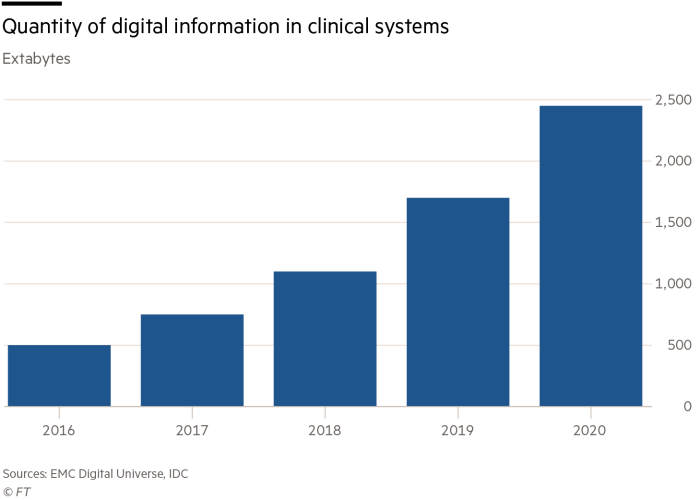

By one estimate, 30 per cent of the world’s total data volume is generated by the healthcare industry, offering detailed insights into who — and how — we are.

And the volume of healthcare data will, according to this research from RBC Capital Markets, grow much faster than the data generated by the manufacturing, finance and entertainment industries.

Making sense of it will therefore be an increasing, but lucrative, challenge. Sensing this opportunity, Big Tech is circling, confident that its Silicon Valley thinking — whether on organising vast amounts of information or harnessing artificial intelligence to fuel new discoveries — will spark a revolution in healthcare.

“Our north star, in some ways, is how we can create tools that give providers a better experience in terms of a more comprehensive understanding of who their patients are,” says Peter Clardy, a senior clinical specialist at Google.

Figures from CB Insights, a market intelligence company, show that almost $7bn was invested in healthcare start-ups by the venture capital arms of Big Tech — Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Google and Amazon — in the year and a half to mid-2021.

Other venture capital funding for digital health start-ups reached almost $40bn globally last year, including a record number of deals. Most of the companies acquired or invested in harness data to create efficiencies in the pharmaceutical sector.

This surge of interest, CB Insights concludes, has been driven by the growing consumerisation of healthcare, thanks to smartphones and wearable technology, an explosion of data, further advances in AI, and a growing realisation that the costs of care, particularly in the US, are spiralling out of control.

The attention from Big Tech coincides with renewed efforts to make healthcare data accessible in ways that were previously off limits, or at least restricted. In March 2020, the US government introduced new federal rules designed to make data sharing easier and more commonplace. The rules were opposed by some hospital association groups and Epic, an electronic health records company, which warned of a risk to patient privacy from third-party apps.

The new rules were welcomed, however, by tech groups and Cerner, another electronic health records provider, which said existing laws that allowed patients to access their data did not work. “Despite the great strides over the past decade of digitising healthcare records, barriers remain in allowing the free flow and exchange of information,” Cerner argues. “Consumers should have the right to access the healthcare information their providers have about them and dictate where they want it to go.”

The attractions for tech companies are clear: they see data interoperability as core to their strategy of supplying tools for healthcare providers, since it lowers the barriers to running a broad range of apps and services. It has led to wide adoption of a data standard, the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, or Fhir, with engineers from leading tech companies taking part in development events that shape how data can become interoperable between health systems.

“These powerful standards have arrived and unlocked the ability to bring together health information in a way that wasn’t previously possible,” Clardy says. “That, from Google’s perspective, has also created opportunities for us to use our experience with organising information and searching across complex information.”

Other Big Tech groups are pursuing similar initiatives to harness data. Apple has focused on patient monitoring through its devices, such as the Apple Watch. Last June, it added a facility for iPhone users to share health data gathered through the device — such as sleep patterns and exercise — with care networks directly.

Facebook, through its Oculus virtual reality division, is working with hospitals on training, while its social network is being used for research and preventive efforts, by prompting users to undergo routine check-ups.

Microsoft has used its cloud platform, Azure, to host apps that are Fhir-compliant for data entry, cleaning and analysing. Last April, the company announced an agreement to acquire voice tech company Nuance in a deal worth $16bn, giving it powerful natural language-processing capabilities, such as enabling a doctor’s discussion of symptoms to be logged and analysed.

Amazon is harnessing its logistics prowess to improve the supply chain, while leaning on its cloud computing division, AWS, to power digital services such as telemedicine. For this, it has used its own workers as a test bed, offering remote care to US employees.

Free-flowing data between these new applications fosters the ability to carry out studies at previously impossible scale and speed. It allows for more accurate predictive care to prevent people becoming ill in the first place and for less guesswork on treatments when they do. It also means breakthrough treatments can be created by AI algorithms and the social determinants of health can be better understood.

Data interoperability could also have profound effects in the developing world, says Steve MacFeely, director of data and analytics at the World Health Organization. Almost all of the world’s population has access to mobile broadband, meaning data speeds of 3G or better, according to the International Telecommunication Union. While rural Africa still lags the rest of the world, it is improving, allowing these healthcare data advances to be extended into regions where record keeping has been held back by a lack of technology and connectivity.

“The whole concept of data itself has changed,” says MacFeely. “Data were numbers. Now data are visuals, they’re sound, they’re text strings. The deluge of data is really a byproduct of the digital revolution. The big challenge is now around interoperability. Of these disparate pieces of data, how do you get them to talk to each other?”

The answer, he says, could be to harness the expertise of Big Tech — but this comes with a warning. “There is huge concern now over data colonialism,” he says, urging Africa to introduce the equivalent of Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation. “The challenge is that if you do it at the country level or a regional level, that still may inhibit the flow of data safely between regions.”

Yet, even with increased movement of healthcare data with Fhir and other initiatives, we may still only be scratching the surface, according to a former Apple executive who left his post in 2018 to tackle the issue of “lost” data between health services.

Anil Sethi was head of Apple’s health efforts but left the company to set up Ciitizen, following the wishes of his younger sister, Tanya, who died of cancer. “We flew Tanya left and right, west coast, east coast, we got her the best treatment,” Sethi remembers. “She was seen at 17 facilities by two dozen physicians and oncologists. So there was this fragmented breadcrumb trail that she left behind her.”

Ciitizen focuses on pulling together some of the insights captured by doctors but not held by existing electronic health records shared between health services. Often, the best insights on a patient’s condition are found in these notes, Sethi says, adding that he finds it frustrating that Big Tech is not making a bigger effort to solve the problem.

The tech giants are “burying heads in the sand and hoping that there’s a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow”, he says. “One of the costs of that is we lose 16,000 people a day to cancer.”

Comments