Nature by design at PAD London 2018

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Our image of contemporary design was once one of spare, minimal forms and smooth surfaces, but that perception has changed in recent years. If the 20th century saw a rush of new options emerge from man-made materials, the aftermath has left us with an environmental consciousness that has prompted many designers to approach nature from a place of humbled curiosity. Some adopt aspects of its visual language, others wonder what it can tell us about efficiency and sustainability, and still more are engaging with the changing face of nature in our age.

Artist and sculptural furniture maker Sasha Sykes has responded with “Gyre”, a structure made from seaweed that should prove a powerful presence at the Pavilion of Art and Design (PAD) fair in London next month. Since 2001, Sykes has collected organic material, flowers, gorse or bird’s nests, which she sets in resin to make furniture. In a single object she is able to capture a whole cycle of seasons, following a seed right to its decomposed end.

“I’ve always been a forager,” Sykes says of a childhood spent in rural County Carlow, Ireland, where she returned in 2006 after living in London and New York. Watching the changing seasons was an instinctive form of time-telling that Sykes lost in the city. “That’s what I craved and wanted to reconnect with most,” she says.

A two-metre-tall folding brick screen, “Gyre”was imagined in the style of the late architect and designer Eileen Gray. It contains an unfurling vortex of myriad seaweed species that Sykes accumulated over 18 months. For her, the appeal of the sea lies, in part, in its role in the Irish landscape: “As an island it’s what defines us, yet everyone turns their back on it.” The plants are also a metaphor for the turbulence of our lives, and in capturing a whirling current, she “wanted to transmit that extraordinary sense of uncontrolled movement and energy that is our introduction to the mystery and uncertainty of the sea”.

Sykes admits to a fear of the ocean, “the unknown world underneath” that is evoked by the seaweeds’ lithe and slippery silhouettes. Sykes is not so much representing the sea as, in her own words, “re-presenting” what is otherwise unseen. No longer emerging from murky depths, the plants have been suspended in an eternal sprawl, lifeless and aestheticised yet brimming with expressive potential.

The natural world is an accidental theme at PAD London this year. Sarah Myerscough Gallery is exhibiting Marcin Rusak’s series of glass vessels, each inlaid with the argent ash of flowers and leaves that have been exposed to the glass-blowing process. Scattered in delicate eruptions, the patterns radiate but are abstracted and rather sedate.

Among the more allusive references to the sea are those of metalworker Junko Mori, presented at the fair by Adrian Sassoon. She claims to weld unconsciously, focusing on micro elements until an accretion arises organically, often resembling coral or sea anemones.

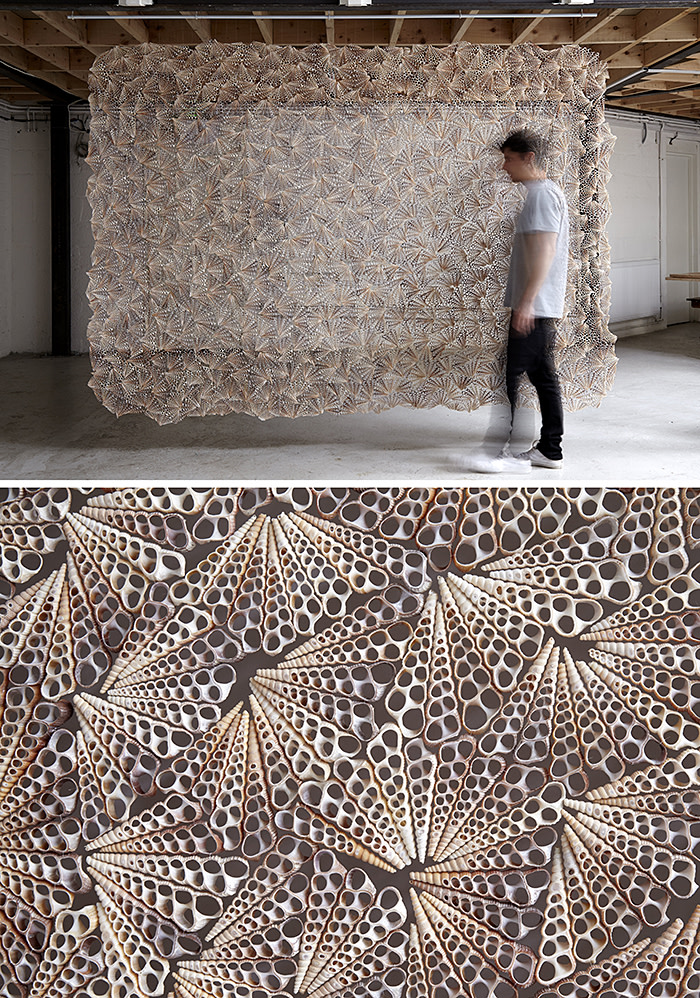

A similarly obsessive repetition of forms can be found on the wall-mounted assemblages of Galerie Fumi’s Rowan Mersh. Up close they reveal the meticulous layering of windowpane oysters or dentalium shells, from a distance they swarm in a mass of rhythmic undulations.

Leonora Petrou of Peter Petrou gallery, which is showing Sykes at PAD, identifies the Enlightenment as “a time of wonder” that brought new discoveries which reignited a western interest in nature and natural forms. Today’s revival is spurred by the realisation of how much remains undiscovered.

Harking back to an earlier era is Steffen Dam, another designer at Peter Petrou, who uses glass to create imagined specimens in his “Sea Life Installation”. Otherworldly and antiquated, their bells and tentacles faintly recall organic forms but ultimately confound the viewer, overwhelming our ability to fathom the natural world.

Exploring the Atlantic coastline in counties Kerry and Galway after the devastating effects of Hurricane Ophelia in late 2017, Sykes was able to collect the delicate red seaweed that ordinarily inhabits the depths. Dried in her kitchen, it shrinks to become jewel-like and has the orangey-pink tint of an autumnal oak leaf when held up to the light.

Sykes credits these discoveries to her association with a growing community of researchers across the west of Ireland, and speaks with great enthusiasm about seaweed’s scientific potential. As biomimicry develops in the field of engineering, the benefits of seaweed — which is durable, light, and does not rely on freshwater or take up precious agricultural space — are attracting interest.

Good design has always been in part about solving problems, and with seaweed’s growing commercial availability, prototypes could become reality. During her residency at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2013, designer Julia Lohmann developed kelp that could be repurposed as leather, plastic or glass.

More recently, the material researcher Nienke Hoogvliet has developed a sea algae yarn to weave carpets and produce chairs and bio-plastic bowls.

Combining seaweed with recycled paper waste, Jonas Edvard and Nikolaj Steenfatt have created a highly durable material with a light, corky texture from alginate, a natural polymer in brown algae. It has so far been moulded into a series of chairs and lamps.

For Sykes, seaweed acts more like a palette than a set of building blocks. She is committed to trusting its natural form and resists the urge to interfere — “once you start playing with it you’re down a completely different road,” she says.

Nonetheless, her approach to nature is not excessively principled or exalting: “I try not to present my work in an overly organic way. I think my form of representing is Brutalist in many ways.” Her use of resin is suggestive of the fossilisation that creates amber, but the intensive sanding and polishing that each block undergoes produces cubes of industrial uniformity.

This, Sykes explains, is what allows us to “take these beautiful forms and make them into something functional”. But the play between organic and artificial is not incidental. Though Sykes looks back to land artists such as Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long, she was recently inspired by Brodie Neill’s “Gyro Table”, a kaleidoscopic swirl that echoes Earth’s latitudinal lines through “ocean terrazzo” — a new material made from fragments of the sea’s plastic waste.

The idea brings to mind Shahar Livne, who sculpts in “lithoplast”, a clay of minestone, marble dust and landfill plastic, which may one day be naturally occurring. Indeed our influences on the earth’s crust increasingly challenge our notions of what it means to exist organically. Once assuming a position of dominance over nature, designers are reconsidering this approach. It is a timely recognition of nature, not as a limitless resource, but as a bounty of untapped potential.

October 1-7, pad-fairs.com/london

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments