Laos unleashed

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Boten-Vientiane railway cuts through the Laotian countryside at a speed of 100mph. Taking the train from Vientiane, Laos’ capital, to Luang Prabang, the seat of its ancient kings, is an adventure that bends time and space. A once seven-hour journey by car is now two, weaving passengers through some of the 75 tunnels carved into the mountains to accommodate it. Green forests flash between stints of black; children press their noses against the glass.

I first came to Laos 10 years ago. There was no railway then; the Boten-Vientiane route opened in December 2021. If you couldn’t afford to fly, travel was limited to the country’s unwieldy dirt roads, navigated with sick bag in hand. Still, I loved it. Revisiting Laos in June – the tangled forests that make up more than 50 per cent of its land area, the miles of mighty Mekong river – only strengthened these feelings.

Surrounded by China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar, Laos is what historian Grant Evans has called “the land in between”, an “arena in which more powerful allies and their neighbours have interfered”. A long period of French occupation (1893-1953) left it with beautiful buildings and an abundance of good pâtisserie, but not much in the way of productive capacity. During the Vietnam war, Laos became the most bombed nation in history: more than a tonne of ordnance for every person living there at the time. Today it is one of the most underdeveloped countries in the world.

But those who visit always return: 2024 has been declared a tourism year. Now they just need the tourists – and, slowly, they are coming. The first quarter of 2023 saw more than 800,000 international visitors arriving here.

Flying across the jungle into Luang Prabang airport, it feels, just as it felt a decade ago, that nothing could change these forest-covered wilds. But today the context is a little different. Laos is in a period of rapid economic investment, trading its natural resources for much-needed foreign currency. There is a flickering worry that this might be the last time I’ll see it like this, with its greenery (mostly) intact. Such concerns, however, are standard for any country that has avoided overdevelopment. I count myself lucky to have even seen it at all.

Luang Prabang sits in the northern part of the country, at the point where the Mekong and Nam Khan rivers converge. The city has been on Unesco’s World Heritage List since 1994, a badge of honour that has kept its culture embedded and its buildings traditional. Tourists know June as low season, when the onset of rain turns the river banks into a garden of lush palms, red Flamboyant and mimosa-like Golden Shower. On a boat tour, I meet Chanthavong Vilayphone (Vong), a local guide, and Allison Gomes, a teacher at Luang Prabang Yoga cooperative. Laos may not have the maritime trade of its neighbours, but it does have the Mekong. The 4,880km river starts in Tibet and winds down through south-east Asia to the South China Sea.

The Mekong has always been a primary life source for Lao people. On the banks you’ll find peanut, aubergine and pumpkin farms – beyond them, in the forests, monkeys, bears and iguana hide. Vong lists the creatures living beneath the river’s surface: Asian redtail catfish (“for laab or the barbecue”), crocodile catfish (“skin like sandpaper”), stingrays and, horror of horrors, cobra and python. Less dangerous are the rat snakes, which apparently taste “like chicken”. But a walk along the river at dusk only reveals children shrieking as they jump from boat to bank.

Today there’s a looming threat to this scene. Work has begun on the Luang Prabang Dam, one of a growing number of hydropower projects up and down the river – part of Laos’ mission to become the so-called “battery of south-east Asia”. Hectares of farmland are being leased to Chinese businesses, raising concerns for local livelihoods. The new railway required $3.54bn of debt financing from China Eximbank; 70 per cent of it is owned by three Chinese state-owned companies. Aside from the environmental impact and displacement of Mekong residents, the Luang Prabang Dam could put a stop to the popular slow-boat journey from northern Thailand. The phrase “debt trap” is occasionally heard.

It’s not hard to understand the appeal of Chinese finances. Pre-pandemic, the Lao kip was worth around 8,000 LAK to the dollar; today the exchange is 18,000. At Wat Wisunarat, a 16th-century temple full of gilded Buddhas and large mahogany beams, Vong fingers a tapestry made from 500 LAK notes, now all but worthless. “Not even the baby wants it,” he jokes, remembering a childhood where one, two and five LAK notes were plentiful. The smallest available today is 500 LAK, equivalent to about two pence.

Yoga and meditation, Gomes explains, are a way to make sense of Lao culture. A native Californian, Gomes has lived here for the past five years. “I kept coming back,” she says. With a population that is more than 50 per cent Buddhist, Laos is about as spiritual as it gets. “There’s no rush – it makes you evaluate your whole western mindset.” After a meditation session by the river, she tells me, quite gravely, that my attitude to work is not sustainable. I admit feeling some burnout; can she tell? A polite “yes”.

Ten minutes south of Luang Prabang centre, Satri House is the perfect place to acclimatise. Once the residence of a former prince, the boutique hotel has 31 rooms, full of dark woods, traditional antiques and colossal four-poster beds. It is, quite literally, the kind of place you can get lost in. I did no less than three times; but someone would always emerge, as if on cue, to quietly direct me through the warren of red-brick staircases and quiet corridors.

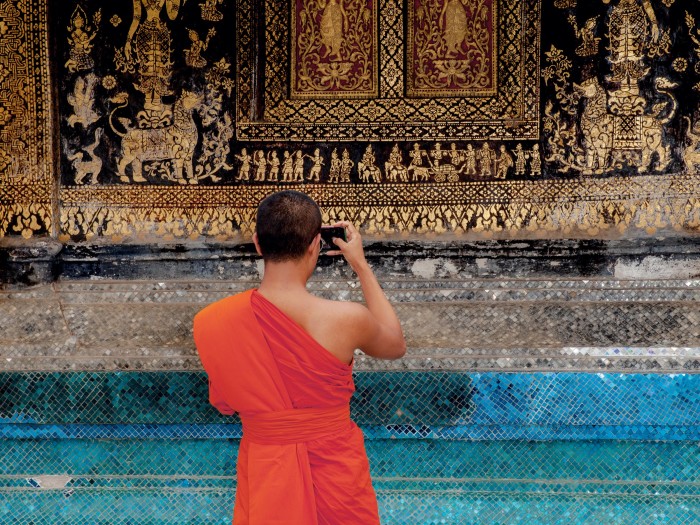

Opposite Satri you’ll find Wat That Luang, one of 32 temples in the city (45, including those in the surrounding villages). Vong takes me on a tour, from the sweeping roofs of Wat Xieng Thong, with its twinkling mosaics and intricate gables, to Haw Pha Bang on the site of the old royal palace. Until 1975, Laos was a conservative monarchy; today it is a one-party communist state. Men can join the temples as young as eight, but are free to leave whenever they wish. Vong himself was a monk for seven years. Of the 227 rules, five are imperative: no sex, no stealing, no drugs, no lying and no killing, not even a mosquito.

You see the monks’ red and orange robes hung on washing lines throughout the city. As well as on the men themselves, as they patter through the streets to collect their morning alms (mostly sticky rice and sweets). Some engage in building work; others hold scriptures written on palm leaves. All have surprisingly shapely arms. (Vong tells me they secretly lift concrete dumbbells in their chambers.)

We finish the temple tour 328 steps up Mount Phousi at Wat Chom Si, where there’s a panoramic mountain view. “In Hong Kong and Bangkok, everywhere is people; in Laos, everywhere is nature,” says Vong, pointing to the distant jungle that we’ll later trek through. To one side of the temple is the Mekong: to the other is the Nam Khan. All around are low-hanging clouds, poised as if nervous to touch the surrounding rice paddies.

Nearly 600 miles down the Mekong in Pakse, the river widens and the temperature soars. The landscape here is that of a forgotten city, with every stilted house caught in a tangle of greenery. Seanamphay Sayaphone (Mook), a guide who grew up in a nearby village, accompanies me to La Folie, a lodge on Don Daeng island with 26 river- or garden-facing wooden bungalows. As the last of the sun peeks through the twisted trunks of swamp trees, we tread cautiously down to the river bank to La Folie’s large wooden raft attached to two longboats: our chariot. Arriving at the island we take a tractor – “Chinese buffalo” – to the lodge at the top of a low, sandy hill. I sleep with the curtains open so as to wake up to the Mekong.

The best thing to do in Pakse is visit the 4,000 Islands, an archipelago on the Mekong Delta famed for its frothy waterfalls and colonial-era buildings. By June, the surrounding mangroves are almost entirely submerged, leaving small rugged bushes that seem to float between each island. The air smells like watermelon.

Despite the sweetness, the area bears a torrid history. Mook explains that the islands’ Liphi Waterfall, meaning “spiritual trap”, is named after the bodies that piled up here in fishing nets during the south-east Asia war. Her parents spent most of this period living underground to escape shelling. The area around Liphi Waterfall, like nearby Khon Phapheng Falls, has been taken over by a Hong Kong-based developer: 150 families have been displaced as the plans for a new special economic plan have taken hold.

That news feels particularly stark when you look at the old railway bridge, built by the French to help connect their various territories. Mook and I watch backpackers make the crossing as we share a plate of pork laab, a salad made with mint, chilli and salty fish sauce – a dish I once thought originated in Thailand. Such confusion is true for many of the fragrant delicacies here – thum mak hoong (papaya salad) is another example – most likely because westerners have learnt about them in Thai restaurants. (When was the last time you ate at a Laotian restaurant?) The country’s position as “the land in between” gives many the impression that it can only be relevant by mirroring its neighbours. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth.

Back in Luang Prabang, I check in to Amantaka. With its airy suites, personal tuk-tuks and placid turquoise pool, the hotel is a strange luxury in this tiny, traditional city. But general manager Tshewang Norbu is committed to breaking Laos’ reputation as an “add-on destination”, and in the most authentic way possible. Cultural programming is as much a feature as the requisite five-star spa, while the hotel restaurant features a daily-changing menu of laabs, soups and stews. Guests can contribute to city life by giving alms in the mornings; in the evening, the preference is a sunset cruise.

The hotel arranges a visit to Monk Somsack at Vat Muenna, the monastery of the royal stupa (Buddhist shrine). Inside the red interiors of the temple, I kneel in front of gold and jade buddhas as Somsack ties a spool of string around a bowl of water, then around me. He invites me to make a wish, which naturally is a secret, before chanting as a long candle drips wax into the water. I ask Somsack how he stays so committed to the temple (he’s 34). “If you only see good things, good things will follow you,” he replies.

On my final evening I play pétanque with Vong while a waitress snaps open a Beerlao as though breaking a chicken’s neck. Gazumping is required. We quickly develop a familiar pattern: Vong knocks me out; we play again. I knock him out; we play again. Much like the rhythms of this slow, meandering country, it’s a game that relies on patience, focus and skill. We can hear the rumbling of the train in the distance. For now, at least, the wheels stay out of sight.

Rosanna Dodds travelled as a guest of Black Tomato; 10 nights in Laos including a stay at Satri House, La Folie Lodge and Amantaka starts from $7,000 per person, excluding flights

Comments