Why British cashmere is still king

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Think of British cashmere, and one might contemplate a romanticised weaving mill nestled in the verdant valleys of the Yorkshire Dales, its handful of looms manned by someone’s grandmother, and perhaps powered by a wooden water wheel. One probably wouldn’t picture a glossy mill on an industrial estate in Batley, a suburban town near Leeds in the north of England.

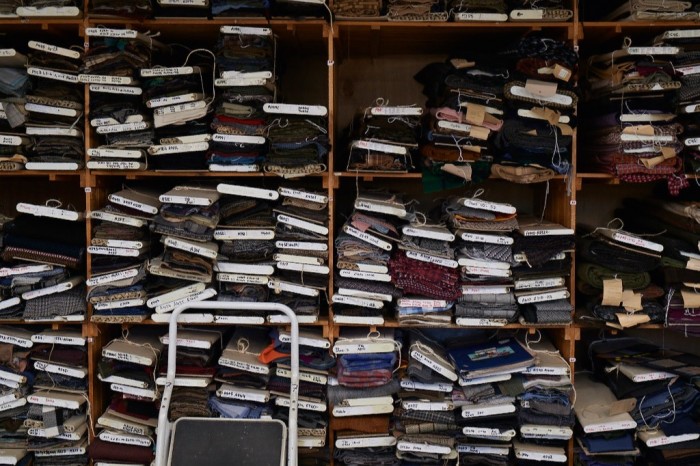

Here resides Joshua Ellis, a 254-year-old cashmere company and one of the oldest and last-surviving weavers in the UK; it moved into this shiny space in 2004. Inside, a rhythmic hum reverberates; looms clank and clatter as strands of superfine yarn are spun into fabric for brands such as Ralph Lauren, Louis Vuitton and Celine. Some are creating monogrammed intarsia patterns; others oversized checks. “This is where the magic happens,” says Oliver Platts, managing director of the family-owned mill.

This month, Joshua Ellis launches its bespoke service in a bid to broaden its client base. For around £3,000, customers can make 7m of their very own cashmere fabric from scratch, choosing the yarns, colours, pattern and wool weight. “We’re basically saying, ‘Come and be your own creative director,’” says Platts. “We can make a blanket with your face on it if you want. It’s basically the same experience that the luxury labels get from us.”

The overall aim, Platts says, is to future-proof the business in a globally competitive, post-Brexit market. Plus, the cashmere market is increasingly saturated with new brands offering a cosmopolitan take on cosy staples. To stay relevant, heritage mills in the UK need to adapt.

Others are diversifying too. This season, Begg x Co launches its first 15-piece womenswear collection of knits, while the Chanel-owned Barrie, situated in the Scottish borders, offers cashmere-mix denim shirts and bucket hats through its own in-house line – a marriage of age-old manufacturing and modern aesthetics. “We’re not all about castles and golf courses and shortbread,” says Ian Laird, chief executive of Begg x Co. “We’re proud of our heritage but we can’t live in the past. Too many backwards-looking brands and factories just die.”

Indeed. “In 1993, there were 12,000 people employed in knitwear within a 25-mile radius,” says Clive Brown, commercial and development director at Barrie. Manufacturing was gradually offshored as brands chased profit and cheaper costs; factories were shuttered. Chanel, a longtime Barrie client, bought the mill in 2012 after its then-owner went into administration. Today, 265 of the 1,000 people employed by mills in Scotland work for Barrie. “The local economy would suffer terribly if we shut,” says Brown. “We’re trying to put a foundation in place for the next 30 years… we’ve got to do things that are really special.” Begg, too, bought another Scottish factory on the brink of closure last year.

Sartorial romantics will enjoy the much-told tales of what makes British cashmere special. It’s washed in crystal-clear waters from the lochs and streams, which gives it a next-level snugness. “We don’t have to add chemical softener,” says Brown. The Brits also knit the cloth tighter, which means it keeps its shape and pills less. So divine is it, in fact, that Begg’s creative director Lorraine Acornley decided to create a largely undyed collection. “It’s just cashmere in its most natural state,” she says.

Ancient machinery helps. In Joshua Ellis’s factory, a tumble dryer-type milling box made of oak softens the cashmere after washing; it looks more like a piece of smart midcentury furniture than an industrial machine. “It’s 75 years old and they don’t make them any more,” says Platts. “You can’t replicate these techniques with modern equipment.”

So far, so traditional, right? Not exactly. “Our guys are overwriting software with their own knitting programmes to make the machines do things completely differently,” says Brown. Barrie’s small team of programmers is 3D-knitting garments in ways “never done before”. Experimentation is key. “It pushes us to try new techniques,” says Brown. “If it doesn’t work for Barrie, it’s not the end of the world. If it doesn’t work for one of our couture brands, it’d be a disaster.” Once they’ve mastered new methods, they’ll pass some of them on to Chanel et al. “The Barrie brand is a shop window so people can see what we can actually do,” he says.

This playfulness is resonating with a younger audience. Begg’s technicolour blanket collaboration with British artist John Booth proved the ideal #interiors fodder, while the Barrie brand is now stocked at Flannels, the British retailer that meshes streetwear with luxury. Sales of its oversized colour-blocked denim jackets, which look like something the members of Destiny’s Child might have owned and take 12 hours to knit, are strong. So too are its branded T-shirts – surprising for a cashmere mill. But in the Instagram era, the Barrie logo demonstrates an air of knowing, and making inroads with this discerning demographic is crucial. “People wear sweatshirts more than sweaters now,” says Brown.

People are also more environmentally aware: the traceability of in-house craftsmanship rather than third-party supply chains is a draw. Barrie is Scotland’s first Global Organic Textiles Standards-certified mill, while Begg tracks its own carbon impact through annual sustainability reports. “Provenance is so important as the younger generation, tomorrow’s consumers, are much more conscious,” says Platts. “We dye and spin all our yarns within a 10-mile radius, our wastewater is treated properly and we don’t use hazardous dyes.” The mill sources its wool directly from farmers, which cuts out middle-men margins and ensures fair wages.

Social responsibility is fundamental. Companies that prioritise people and the planet as much as profits are increasingly where the younger demographic will spend, according to Deloitte. Its 2021 survey of the impact of Covid-19 among millennials and Gen Z found global wealth inequality is their fourth ranked concern, with the climate taking priority; almost one in five have boycotted companies whose actions conflict with their values. “We pay everyone a living wage and we don’t use underage labour across our supply chain,” says Platts.

This consolidation is perhaps best exemplified by a single scarf that dangles from a hanger in Joshua Ellis’s meeting room. Charcoal grey with tasselled edges, it’s emblazoned in capital letters with the phrase “Human Rights” – the mill crafted it for New York menswear label Noah, launched by former Supreme creative director Brendon Babenzian. “These two words, woven into a piece of clothing, are like a light shining in the darkness,” said the brand upon its release. “It’s a banner and reminder of this simple, human principle, in times when it is being callously ignored.” Cool, conscious cashmere as a means of communication – it’s a far cry from castles and shortbread. The question now is, what does your knit say about you?

Comments