Jony Ive and Prince Charles have picked us to save the planet

Simply sign up to the Sustainability myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2021, as part of his Sustainable Markets Initiative and in the year of COP26, the Prince of Wales set out his Terra Carta (Charter for the Earth) to urge big business to put the health of the planet at the heart of its agenda. He wrote: “If we consider the legacy of our generation, more than 800 years ago, Magna Carta inspired a belief in the fundamental rights and liberties of people. As we strive to imagine the next 800 years of human progress, the fundamental rights and value of nature must represent a step-change in our ‘future of industry’ and ‘future of economy’ approach.”

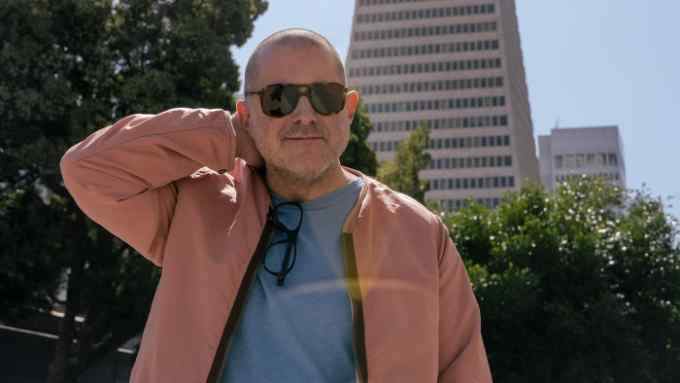

The Prince is the Royal Visitor at the Royal College of Art in London; Sir Jony Ive is its chancellor; and that connection led to the founding of the Terra Carta Design Lab. It is heralded by a prize to inspire current RCA students and alumni from 2011 to 2021 to explore “local initiatives to restore biodiversity, reduce greenhouse gases, support developing countries, and catalyse a new economic and social model that realigns people with their environment”.

“There is a wonderful connection between His Royal Highness and the Royal College, and I’ve always been struck by his preoccupation with these extraordinary problems that we’re facing,” says Ive. “I was particularly excited to work with him to establish this initiative because, despite the challenge, I found his whole approach incredibly encouraging. It’s very easy to be so overwhelmed by the nature of the crisis and it’s an enormous privilege to become involved in something that is fundamentally forward-looking and optimistic.”

The four winners, announced on 27 April, were selected by a panel of judges including the Prince of Wales, Ive, vice-chancellor of the RCA Paul Thompson, and supporting partners of the Terra Carta Design Lab and the Sustainable Markets Initiative. The winners each receive a prize grant of £50,000, will be mentored by Ive and have access to the network of the Prince’s Sustainable Markets Initiative. What was striking about the submissions that were first showcased as a shortlist of 20 was the positivity of the students and the diversity of the projects on show. Also striking was the multidisciplinary nature of the teams, bringing together young architects, designers, scientists, engineers, textile designers and artists – a 21st-century compound of CP Snow’s “two cultures”.

“From my personal experience, the best ideas are the result of a very open, multidisciplinary collaboration,” said Ive before the showcase. “Absolutely everything I’ve worked on of any consequence has been the result of engineers and scientists and designers and artists working together. And the uniting thread – in addition, of course, to being galvanised by having similar values – is curiosity.”

One of the four winners, Francisco Norris (MA information experience design 2017) grew up in Argentina between Buenos Aires and his family’s cattle operation in the Pampas. “Agricultural methane is by far the number-one source of man-made methane globally,” says Norris of his effort to find an answer to the gas’s impact on global warming. “After COP26, the global methane pledge was signed by 105 countries to reduce methane by at least 30 per cent in the next eight years.”

His solution? A device for cattle to wear that will capture the methane as it leaves their body. But if you imagined that would be positioned at the rear of the animal you’d be wrong. “Because cattle have four stomachs, 90 to 95 per cent of the methane that they emit comes out of their mouth and nostrils,” explains Norris, patiently.

The device catches the gas in a halter with a specially adapted nose-piece that collects the gas the animal exhales and directs it into a catalyst under its neck; the catalyst breaks down the methane into carbon dioxide and water vapour. Carbon dioxide also contributes to global warming but, says Norris, it’s much less harmful than methane, “considered to be 85 times worse for global warming because of the amount of heat it traps in the atmosphere”.

Another of the winners is addressing a problem that remains more under the radar: the pollution caused by wear on cars’ tyres. The rubber “dust” that comes off our tyres is actually calculated to be the second-largest microplastic pollutant in our environment, say Siobhan Anderson, Hanson Cheng, and Hugo Richardson (all MA/MSc innovation design engineering, 2020) of The Tyre Collective. “We were looking into research on microplastics and we kept seeing ‘tyre wear’ coming up,” Anderson says of their baptism into the world of microplastics. “We didn’t really know much about it at first.” It’s an issue that has become even more pressing with the rise of electric vehicles that, although cleaner in terms of engine pollutants, are set to be much dirtier in terms of tyre wear because they are both heavier – due to their batteries – and can also accelerate more quickly than traditional cars. The prototype solution they have created is a box that sits behind each of a car’s wheels, using electrostatics to attract and gather the dust as the wheels turn.

The benefits are twofold: the air we breathe should be cleaner; and the particles gathered can be recycled into new tyres, the soles of shoes or other such rubber products. As with Norris’s halter, the question is how to translate research lab results into real life. “In the lab we capture about 60 per cent of the airborne particles,” says Cheng. “But in our recent on-vehicle test we were looking at about 20 per cent. We’re aiming to improve that to 50 per cent in the next year or so.”

“I think the most shocking thing that we found is that while there is little public awareness about tyre wear, within the industry it’s quite a well-known problem,” says Cheng. Anderson adds, “But there’s nothing that’s really looking at creating directional solutions yet.”

When Anderson and Cheng outlined their project to Ive, he told them that he’d never thought about tyre wear, says Cheng. “And I was like, ‘Now you’re not going to stop thinking about it, so welcome on board.’”

Like The Tyre Collective, Amphibio, a team of eight, set out to explore one problem and found themselves solving another. “Originally, we were looking at creating artificial gill technology for underwater breathing equipment,” says CEO Jun Kamei (MA/MSc innovation design engineering, 2018). The material they created, Amphitex, a form of polyolefin textile, is both water-repellent and breathable – it is also potentially 100 per cent recyclable. “We realised that we could use it for other applications such as outdoor sportswear that [needs to be waterproof and breathable]. Most outdoor wear is impossible to recycle, so if you have a jacket [by a well-known label] it’s going to go into incineration or landfill. The other thing is that brands use a chemical called a PFC – a fluorocarbon – to make the garment water-repellent, and they’re not great because some have carcinogenic effects.”

Beyond sportswear, the team believes the recyclable textile could be used in the medical industry as PPE, and also in food packaging. While the focus so far has been on developing the textile and membrane technology, more work needs to be done “in the recycling field”, says Kamei. Winning the Terra Carta Design Lab prize will enable them to kickstart this next phase of development and secure additional funding.

Begum and Bike Ayaskan (both MA design products, 2015) are, meanwhile, very much in the earliest stages of development. Identical twins, they went to high school in Turkey and studied architecture in the UK. In 2016 they set up Studio Ayaskan to create works of art that blur the boundaries between disciplines, “exploring connections between nature, time, objects and spaces” – a plant pot that would grow with its occupant; a work of art that would melt and recrystallise depending on the brightness of the light. “We were very much obsessed with nature, nature cycles and observing what was happening. And on the other side, we also got super into environmental research and environmental design,” says Begum.

The focus for their project is on regenerating and reforesting, starting with pilot projects first in the UK, and then Turkey. “One third of the world’s soil is [severely degraded] right now,” says Begum. “So we’re going to have two parts to the project. The first two to three years we’ll focus on healing the soil and then we’re going to start introducing the seeds to start the regrowth. Because without healing the soil, the seeds’ survival rates decrease quite a lot – and we have a seed shortage in the world as well – so we’re just increasing its chances to recover itself and create its own balance.”

The plan is to achieve this refertilisation and replanting of the land from the air, somehow moulding waste foods (“Coffee grounds are very good,” says Bike; “Banana peels, orange peels, tea leaves…” adds Begum) into the shape of parachute-like sycamore/helicopter seeds that will gently and elegantly pirouette to the earth (“We might use crop-dusters, or there are solar-powered planes, but we have to work out the cost versus the benefit,” says Begum). The next step is to use similarly moulded “parachutes” to carry seeds for replanting. All Begum and Bike have now is prototype versions that float to earth – beguilingly beautiful in themselves. “But the challenge will be to make them self-assembling by pressing them into shape, because we want to make it so that everyone who wants to get involved with the project can easily replicate it in their geographical location,” says Begum. “We’re going to design everything soon,” she adds.

Precisely the kind of can-do optimism Terra Carta and the future needs.

Comments